Story of humanity a work in progress

OPINION: A scholarly study of the origins of inequality produces surprising results.

OPINION: A scholarly study of the origins of inequality produces surprising results.

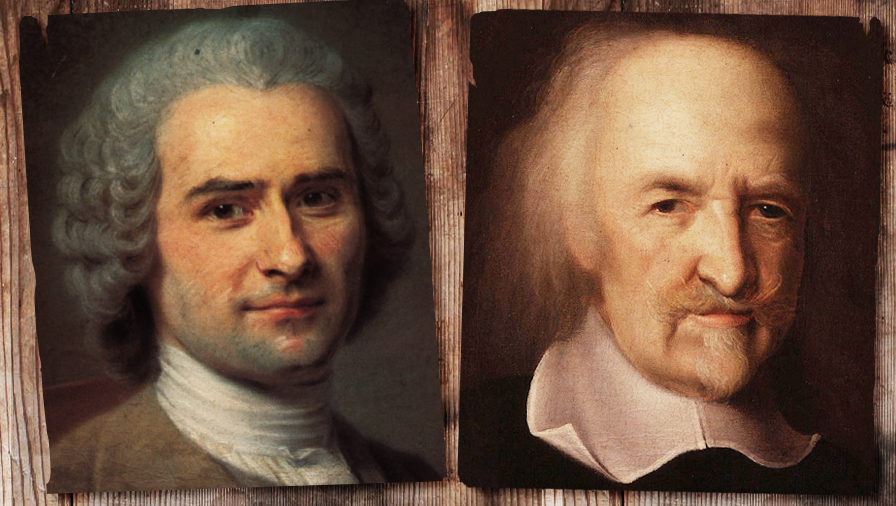

The causes and cures for inequality have been an intellectual concern since the French philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau published A Discourse on the Origins of Inequality on it in 1754 when he was 42. His ideas provided an early inspiration for the French Revolution of 1789, though his thinking went through several more stages in later life.

These notions were first expressed a century earlier by the British philosopher Thomas Hobbes, who stated that human history was a developmental process governed by changes in technology and social arrangements. To Hobbes, life was “solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short”. It was based on selfish material motives and fear of death. This justified societies having rules to curb these base instincts.

For Rousseau, early humans evolved into this state from egalitarian hunter-gatherers. Technology including use of metal tools; domestication of livestock; and cereal agriculture had enabled this transition into settled societies based on private property and the beginnings of urban living.

Further progress came from the growth of capital, disparities of wealth, and power structures that created oppression, slavery, and other evils that remain social issues into the modern day.

The study of early human history was traditionally the field of archaeologists and later anthropologists, more recently giving way to ‘long view’ bestsellers by popularisers such as Jared Diamond, Steven Pinker, and Yuval Noah Harari. Mostly, these confirmed a lineal story from savagery and barbarianism to civilised societies, with democracies sitting at the apex.

But not everyone accepted this conventional view. Concerns about inequality in Europe during the 17th century, when Hobbes was writing, arose from stories by explorers, traders, and missionaries about primitive societies that showed no evident signs of poverty, were caring toward the old, and enjoyed freedoms from lives of just toiling the land.

‘Long views’ of history

These are the opening scenes for the latest ‘long view’ of humanity, The Dawn of Everything, by the late anthropologist David Graeber and archaeologist David Wengrow. Their book – of some 690 pages, including notes, sources and index – is a quantum larger than some of those by the authors named earlier. (An exception is Pinker’s The Better Angels of Our Nature, which runs to 800 pages.)

No-one will doubt the scholarly credentials of Graeber and Wengrow, though their conclusions have met widely varying responses. Graeber, who died in September last year just after completing a decade’s work on the book, was well known for his anarchism. He moved from the US to the London School of Economics in 2008, and was an inspiration for the Occupy Wall Street protests against capitalism that spread around the world in 2011.

Wengrow has a much lower profile at University College London. Their collaboration is a full-scale assault on Hobbes and Rousseau, rubbishing their respective views that early man was thuggish until tamed, or lived in idyllic innocence until becoming civilised.

Though daunting in length and detail, with a bibliography running to 63 pages, this is a provocative, gripping, and societies-fascinating read, particularly if you are not familiar with non-European civilisations going back some 40,000 years when homo sapiens began to emerge as the only human species.

The authors argue a case, often with humour and occasional glibness, that contradicts long-held assumptions about the origins of inequality, the nature of freedom and slavery, the roots of private property, and the relationship between people and the state.

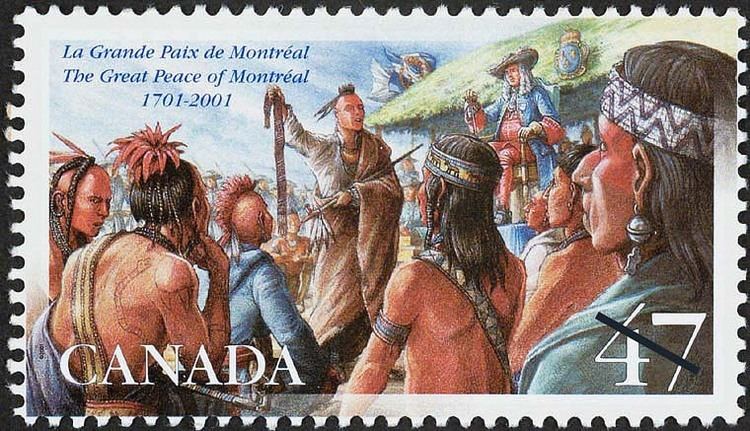

The starting point is a Native American critique of European society, attributed to a ‘dialogue’ between Kandiaronk, a Huron-Wendat chief (from today’s Quebec), and Louis-Armand de Lom d’Arce, or Baron de la Hontan, who published the account in 1703.

Among Kandiaronk’s observations was that “money is the devil of devils; the tyrant of the French, the source of all evil”. And what kind of humans “only refrain from evil because of fear of punishment,” he wondered. On a trip to France, Kandiaronk was horrified by the king’s treatment of his subjects; in the former’s culture, torture and worse were reserved for outsiders.

Origins of inequality

The work of Lahontan, as he became known, led to the claim, which some would dispute, that up until then European intellectuals had no concept of social inequality. “[T]he indigenous critique would come as a shock to the system, revealing possibilities for human emancipation that, once disclosed, could hard be ignored,” Graeber and Wengrow write.

Critics point to Pope Gregory the Great, among others, who in the sixth century asserted social equality and that wishing “to be feared by an equal is to lord it over others, contrary to the natural order”.

Graeber and Wengrow cast a wide net for any signs that humans could organise themselves, with or without agriculture, in ways that didn’t depend on male-dominated hierarchies, bureaucracies, classes, and other paraphernalia of modern capitalism.

In some cases, critics assert, Graeber’s anarchism encourages him to make assumptions from often inconclusive evidence. In turn, the authors are scathing toward versions of history they say bury notions of alternative social arrangements.

One involves large-scale Neolithic communities of the first farmers, discovered in Turkey, that could have been self-governing and resistant to inequality over a thousand years, depending on how you read the evidence from the style of houses and other remains.

A tiki tour of such societies naturally includes gender issues, with the authors stating that definitions of so-called egalitarian societies are difficult in the absence of clear roles for the sexes, or the practice of nomadic tribes to combine cultivation in wet seasons with foraging and hunting at other times. Changing circumstances required different forms of societal organisation, which were described in a plethora of detail once anthropology became an obsession of Westerners during the era of empire-building and colonisation.

Drawing conclusions

Graeber and Wengrow draw plenty of conclusions from these myriads of sources. For example, humans are distinct from animals in producing surpluses for their needs. While Marxists see the possibility for this to be distributed collectively in a form of communism, most anthropologists would view true egalitarianism as possible only by eliminating any surplus accumulation.

Food production was the basis of any culture and became easier as the Earth warmed, with many new resources becoming available. This negated or reduced the need for farming, another challenge to the linear progression theory.

The need for less farming has been described as the ‘ecology of freedom’, as it allows time for other activities, including leisure pursuits. Oceania makes a brief appearance at this point, around 1600BC, when Neolithic communities used the first deep-ocean outrigger canoes to move from rice-based growing in Taiwan and the Philippines to tropical islands more suited to prolific tubers and fruit.

Fiji, Samoa, and Tonga were settled by so-called Lapita groups, named after a site in New Caledonia where their decorated pottery was first identified. Though few archaeological traces remain, the Lapita tradition is continued in body tattooing.

Chapters on the formation of cities, and whether they were bureaucratic or decentralised, as well as having social housing, provide further examples that human settlement didn’t automatically mean concentration of wealth and power by an elite.

‘Rather than an investigation of the chimera of egalitarianism, it reveals a rich tapestry of reactions to hierarchy and dominance.’

Some of the most interesting accounts of differing social structures describe the Mesoamerican civilisations of Central America that preceded the arrival of the Spanish. This has become an area of controversy, as the conventional view of a technologically superior military conquest gives way to more nuanced responses from both centralised and decentralised societies.

Few readers will come away from this book without knowing much more about how humans have evolved over tens of thousands of years, and how these affect modern thinking. Rather than an investigation of the chimera of egalitarianism, it reveals a rich tapestry of reactions to hierarchy and dominance. These include expressions of freedom that allowed people to leave or move away from groupings they didn’t like, or to disobey instructions that couldn’t be enforced.

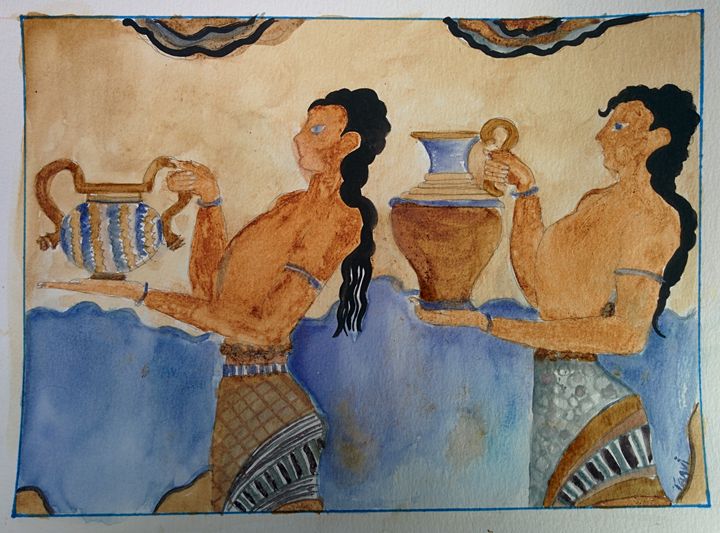

Topicality lies in the source material being gendered throughout, highlighting the role of women for their mental achievements in using solid geometry and applied calculus for weaving and architecture, as well as advances in plant cultivation, food production, natural medicines, textiles, and ceramics. The Minoans are considered a matriarchal society.

While you may think, correctly, that some of the authors’ claims are exaggerated, and are contradicted in the source notes, this book has a status that will last into the future. Their formula is to make their assessments first, backing them up to varying degrees with the scholarship. It makes reading easier, if frustrating, when you want to challenge the conclusions.

The Dawn of Everything: A new history of humanity, by David Graeber and David Wengrow (Allen Lane).

Nevil Gibson is a former editor at large for NBR. He has contributed film and book reviews to various publications.

This is supplied content and not paid for by NBR.