Speaking truth to power: no laughing matter

How black humour helped defeat communist regimes in Europe.

WATCH: NBR columnist Nevil Gibson speaks with Calida Stuart-Menteath.

How black humour helped defeat communist regimes in Europe.

WATCH: NBR columnist Nevil Gibson speaks with Calida Stuart-Menteath.

London is a booklover’s paradise. That has been the case for as long as anyone can remember – as a centre of English-language publishing as well as for its plethora of bookshops.

On a recent visit, I returned to some old haunts and found a few new ones. A tourist from, say, New Zealand is immediately struck by the number of outlets selling new books. These are dominated by three main chains – Foyles, Waterstones, and WH Smith – as they appear in most major railway stations as well as main street shopping or in malls.

Some have embedded cafés, while WH Smith is now more of a convenience store than a newsagent. Then there are the specialist bookshops dedicated to just about any activity you wish to name.

Outside the Marx Memorial Library. Photo: Nevil Gibson.

Take Daunt Books, whose Marylebone outlet is a marvel of Edwardian design. It arranges its three level of books, many of them about travel, by country of origin. Or the Foyles flagship store in Charing Cross Rd with its five floors and 200,000-odd titles.

Another that emphasises size is Waterstones-owned Hatchards, next to Fortnum & Mason in Piccadilly and not looking anything like its chain-store siblings. Hatchards claims to be the UK’s oldest bookshop, opened in 1797.

In another life, when I was younger and interested in working-class politics, I remember visiting Central Books in Gray’s Inn Rd in the heart of literary London, better known as Bloomsbury. Central Books is no longer a bookshop but has a distribution business in the East London suburb of Dagenham.

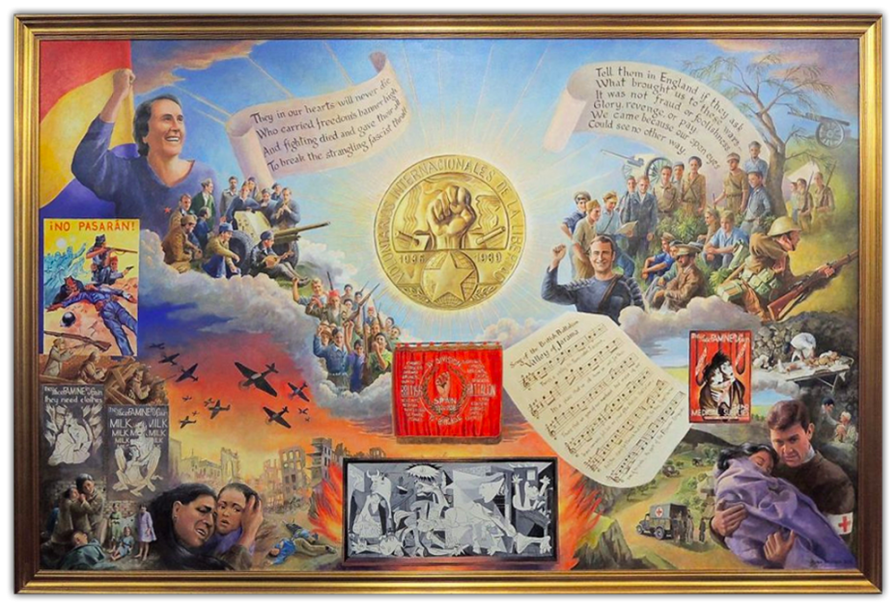

My first stop, near Farringdon Rd station, was the Marx Memorial Library, where I had a look around its books, said to be the largest collection in the UK on the labour movement. On one wall was a large mural-style painting by Rosa Branson marking the 75th anniversary in 2011 of the International Brigades in the Spanish Civil War. Elsewhere is another by Viscount Jack Hastings (known as the ‘Red Earl’) in the style of Mexican artist Diego Rivera. It promised new dawn for workers that would sweep away the chaos of capitalism. It never happened.

Rosa Branson’s painting in the Marx Memorial Library.

I bought Andrew Rothstein’s history of the building overlooking Clerkenwell Green, paying the £1.95 ($4) printed on the cover of a 1983 edition. New paperbacks of that size now sell for £10.

Housmans in Caledonian Rd, London. Photo: Nevil Gibson

At the King’s Cross station end of Gray’s Inn Rd I found radical books were still the core business of Housmans on Caledonian Rd. Not far away is the Dickens House Museum and the British Museum, where Marx spent much of his time writing. (The museum’s reading room is now an exhibition area as the books were transferred to the separate British Library, next to St Pancras and King’s Cross stations.)

Housmans was founded by pacifists in 1945 and has survived by stocking neo-Marxist books on feminism, race, colonisation, and gender issues rather than the economic struggles of the working class.

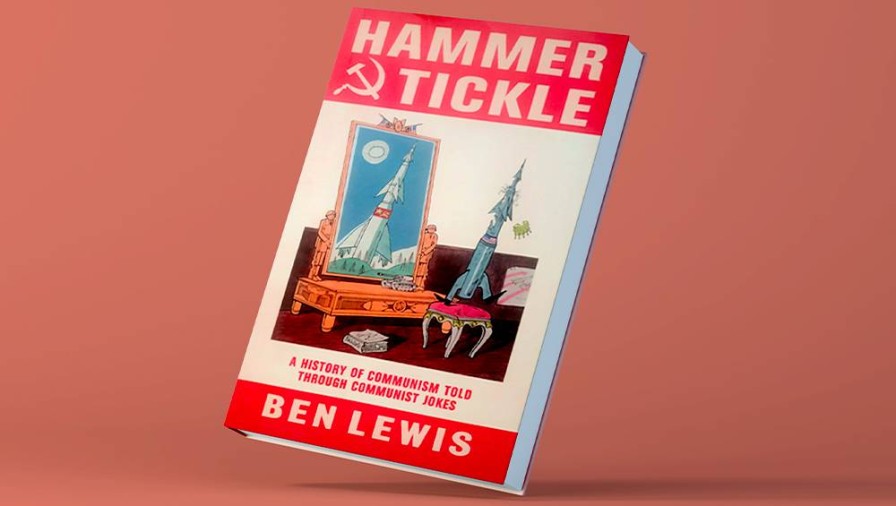

It is rare among London bookshops, outside of second-hand ones, in having a large bargain basement. It was in the main store I found the most unlikely book on my trip: Hammer & Tickle, a history of communism told through its jokes, by TV producer Ben Lewis.

In 2006, Lewis produced a documentary, subtitled The Communist Joke Book, for BBC4 and later wrote about his research in an article for Prospect, a highbrow magazine. It proved so popular he turned it into a scholarly book of 350 pages.

Author Ben Lewis.

The title, as you might have guessed, was so good Lewis couldn’t resist reusing it. The original was a self-published book by Petr Beckmann, a Czech-born professor of electrical engineering in Colorado. He was a prolific writer in his area of speciality, including advocacy of nuclear power, as well as an anti-communist. His first book on communist jokes was Whispered Anecdotes: Humour from Behind the Iron Curtain (1969).

Thanks to Beckmann and dozens of others, Lewis found a trove of published material in many European languages on the use of humour in totalitarian and authoritarian societies, some dating back to Prussian Germany. Many of these were anti-Semitic and repurposed in the 20th century to tragic effect by Nazi Germany.

Similar jokes surfaced in the Soviet Union from the early Stalinist era and in Eastern Europe during the Cold War.

George Orwell recognised the role of humour in Nineteen Eighty-Four, describing “every joke [as] a tiny revolution”. This was reinforced by the Czech writer Milan Kundera’s The Joke, first published during the brief ‘Prague spring’ of 1968 before the Soviet invasion. In it, the hero was sentenced to hard labour for sending his girlfriend a postcard saying: “Optimism is the opium of the people.”

Milan Kundera in 1980. Photo: Elisa Cabot.

Lewis doubts this form of rebellion brought down the communist regimes but as a political system that failed to deliver on its promises, it created a unique brand of humour. This compares with, say, Islamic societies, where political humour is largely absent.

From Stalinist times, jokes were banned and perpetrators often received serious punishment. The subject matter ranged from aspects of daily life, such as queues for scarce consumer goods, to personality cults, propaganda in the official media, and even the theories of Karl Marx.

Communist authorities were aware of this and encouraged the publication of at least one official publication dedicated to satire. Krokodil, first published in 1922, was the original template for Szpilki in Poland, Dikobratz in Czechoslovakia, Ludus Matyi in Hungary, and Eulenspiegel in East Germany (DDR).

They specialised in lampooning Western politicians and capitalist warmongering. Domestic content was mainly about incompetent bureaucrats, who were blamed for all the allowable ills admitted by communist societies.

Belief in communism persisted long after these regimes disappeared from Europe after 1989. Lewis explains this through his girlfriend, who grew up in the DDR and, though aware of a better life under capitalism, was still angry at the levels of inequality, poverty, low migrant wages, environmental degradation, and other forms of exploitation in the West.

This dichotomy is a continuing theme, as Lewis interviews former ministers in communist governments for their views of anti-establishment humour. For them, jokes were a means of ‘letting off steam’ but not an existential threat to the system. One expert described these jokes as a thermometer not a thermostat.

“The humour of the communist joke erupts from the explosive tension between embrace and unmasking, devotion and abuse, affection and contempt,” Lewis says in one of his more analytical observations.

These contradictions existed in the DDR, which had no official censorship. But ‘mistakes’ were severely punished. At least two issues of Eulenspiegel were pulped and republished because the covers, one featuring long-haired hippie youth, were considered unacceptable.

One expert described these jokes as a thermometer not a thermostat.

Lewis considers the ‘golden age’ of communist humour was the 1960s ‘thaw’, when arrests of joke tellers had stopped and controls over freedom of expression were relaxed. This was followed by a period of stagnation in the 1970s and 1980s as “jokes became longer and less funny”.

Mikhail Gorbachev, left, and Ronald Reagan in 1987. Photo: RIA Novosti archive.

Opposition to communism became more serious, with the growth of samizdat (underground publishing) and pressure for reform. Emigration, particularly of Jews from the Soviet Union to Israel, was another means of managing dissent.

This was countered by greater apathy and complacency, as resistance was replaced by acceptance. The emergence of Mikhail Gorbachev was a response to the growing belief the Soviet system could not survive without change. He was constantly tormented by US President Ronald Reagan, who loved retelling communist jokes in all his speeches.

According to the man who collected these jokes, Reagan believed the “Soviet people were appalled by their government … its stupidity, its limitations, its arrogance, and therefore they were interested in being free, and they would welcome a change in the political system.”

In his conclusion, Lewis states that communism – because of its false belief in a utopia – was inherently ‘funny’ compared with other ideologies, such as capitalism, imperialism, fascism, and fundamentalism, due to its unique combination of factors.

“The ineffectiveness of its theories, the mendacity of its propaganda, and the ubiquity of censorship were all important. The cruelty of its methods interacted with the sense of humour of the people on whom it was imposed.”

The concentration of power in the state, and its attempt to direct artistic activities, inevitably meant any joke critical of life in a communist society was also about communism itself and its “greatest cultural achievement”.

Note: The documentary Hammer & Tickle: The Communist Joke Book is available from iTunes. Extracts are on You Tube.

Hammer & Tickle: A history of communism told through communist jokes, by Ben Lewis (Phoenix).

Nevil Gibson is a former editor at large for NBR. He has contributed film and book reviews to various publications.

This is supplied content and not paid for by NBR.