Salman and me – encounters with a blasphemer

Hate motivated Rushdie’s attacker but ideas can’t be killed.

NBR columnist Nevil Gibson speaks with Fiona Rotherham

Hate motivated Rushdie’s attacker but ideas can’t be killed.

NBR columnist Nevil Gibson speaks with Fiona Rotherham

The long arm of the Islamic Republic of Iran’s fatwā finally reached Sir Salman Rushdie as he was about to give a lecture at the Chautauqua Institution in the state of New York. The institution is named for a 19th century social movement that promoted adult education in rural America.

A fatwā has the opposite purpose. To quote Rushdie’s account, Iran’s Supreme Leader, Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, said: “I inform the proud Muslim people of the world that the author of the 'Satanic Verses' book, which is against Islam, the Prophet and the Quran, and all those involved in its publication who were aware of its content, are sentenced to death. I ask all Muslims to execute them wherever they find them.”

Protesters in Paris calling for Rushdie’s death.

The fatwā was accompanied by a reward of US$3 million. Thankfully, few took up the challenge, first posted on St Valentine’s Day, February 14, 1989. But as hate speech it had an immediate effect. Some 45 people died, most of them in riots in Pakistan, where blasphemy against Islam is still punishable by death.

Of course, probably no one there or in other protests and bookshop bombings had read it. But one who had, and was stabbed to death, was Japanese professor Hitoshi Igarashi, who translated it. The Italian translator, Ettore Capriolo, and the Norwegian publisher, William Nygaard, were seriously injured in attacks, just as Rushdie himself was on August 12.

First encounter

I first encountered Rushdie at the inaugural Adelaide Writers Festival in March 1984. It was the first international literary festival in this part of the world, attracting such names as André Brink (South Africa), Angela Carter (UK), Bruce Chatwin (UK), Françoise Gilot (France), Russell Hoban (US/UK), Per Jersild (Sweden), Keri Hulme (NZ), John McGahern (Ireland), and DM Thomas (UK). Australia’s representatives included Blanche d’Alpuget, AD Hope, Elizabeth Jolley, Thomas Keneally, and Morris West.

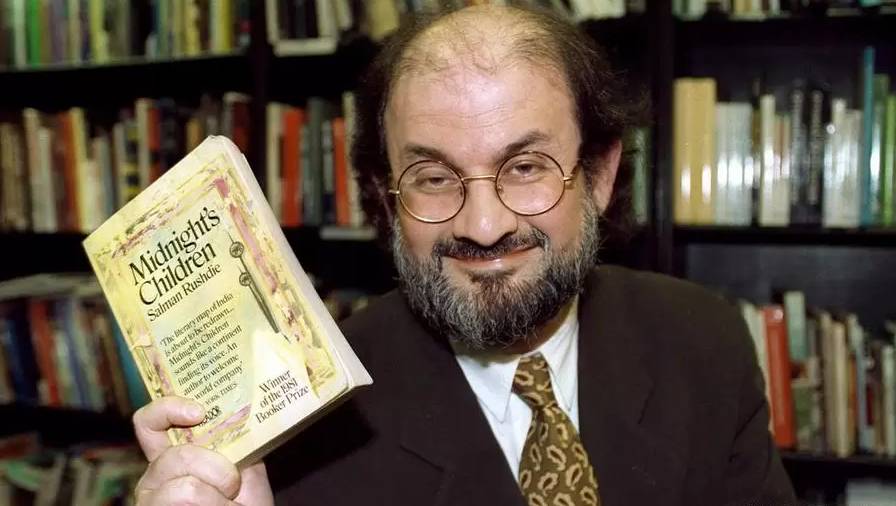

Midnight’s Children was the best novel of all the Booker Prize winners.

Rushdie was then the celebrated author of Midnight’s Children, which won the Booker Prize in 1981 and was deemed to be "the best novel of all winners" on two occasions, marking the 25th and 40th anniversaries of the prize.

It remains his most accessible novel and was made into a reverential film that summarises the plot but fails to capture Rushdie’s formidable use of the English language that made it so famous. The Adelaide festival was remembered mainly for Rushdie’s comments that the city was “the perfect place to set a horror story”.

Coming from Christchurch, as I did then, the similarities between these two cities were striking. They were colonial towns with strong religious traditions, a grid street layout, and a reputation for bizarre crimes. (Peter Jackson’s Heavenly Creatures and Lynley Hood’s A City Possessed come to mind.)

You know why all those films and books are always set in sleepy, conservative towns? Because sleepy, conservative towns are where those things happen. Exorcism, omens, shining, poltergeists. Adelaide is Amityville, or Salem, and things here go bump in the night.’

Next encounter

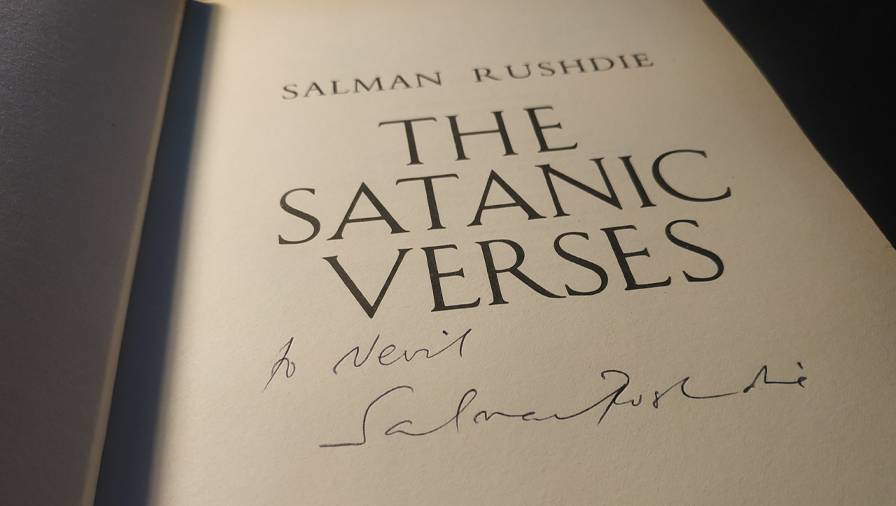

My next encounter with Rushdie is lost in the fog of memory. Somehow, he signed my first edition copy of The Satanic Verses, published in 1988. Google has no record of a book tour to New Zealand. I may have got it on an overseas trip.

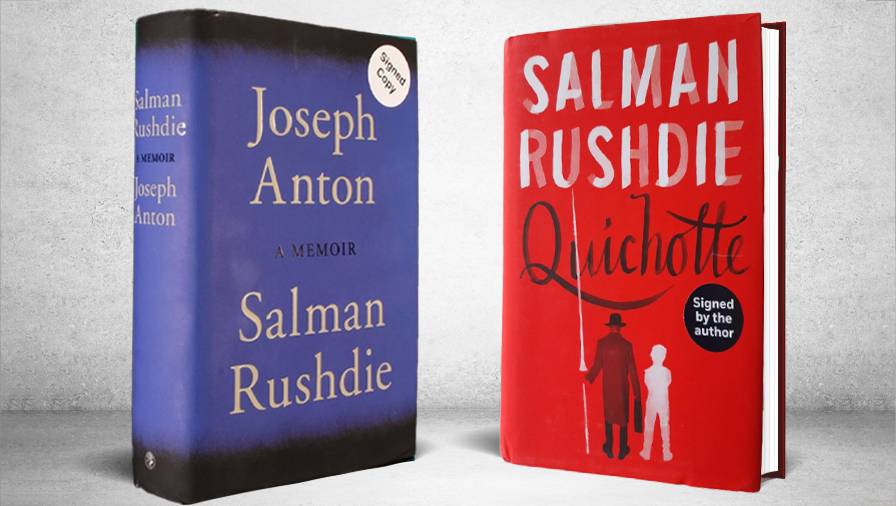

The NBR archive has a review of Joseph Anton (2012) while Paul Holmes did a remote interview with Rushdie for TV One in 2015.

Joseph Anton is a memoir written in the third person. The title refers to the alias he used while in police protection and is based on the first names of Conrad and Chekhov. It reveals how much his experience in Australia provided material for the novel.

Themes such as what he called the “pain of the generations,” migration, Dreamtime, the lost child (Azaria Chamberlain), and prophets from the deserts recur throughout. Patrick White’s Voss (1957), about a Prussian explorer and naturalist who disappeared in the Australian desert, is also referenced.

Rushdie was accompanied by Chatwin on his first Australian trip. They found a copy of Robyn Davidson’s Tracks in an Alice Springs bookshop. It is an account of Davidson’s 2700km solo trek across the Gibson Desert accompanied by camels.

Outback experience

Chatwin arranged an introduction and the pair had a three-year affair, during which she took Rushdie into the Outback, giving him a taste for life in the wilderness, sleeping under stars, as Moses and Mohammed did. It was memorably filmed with Mia Wasikowska in 2013.

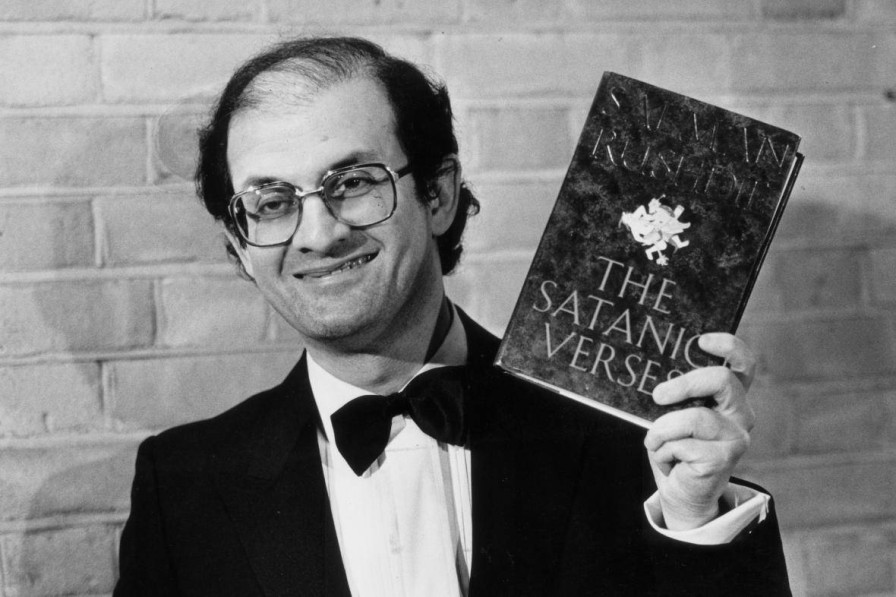

Salman Rushdie with a first edition in 1988.

As for the ‘satanic verses’ at the centre of the controversy, Rushdie provides the background to the founding of Islam in Joseph Anton, based on his university studies at Cambridge. His Indian Muslim parents arranged for his education in Britain, and later moved from his birthplace, Bombay (now Mumbai), to Pakistan, a country Rushdie despises.

In Rushdie’s telling, Muhammad ibn Abdullah was a wealthy merchant who spent periods of solitude in the Arabian desert. He hears the message of God from the Archangel Gabriel and is inspired to revive the vanishing code of nomadic Arabs, with its matriarchal values of a caring society.

Like Jesus Christ before him, this was a revolutionary challenge to the Arabian rulers of the time, in this case Mecca. And, like Moses, Muhammad the Prophet brings sayings from the mountain that sum up Islamic teachings.

In one case, he repents against Mecca’s worship of three goddesses, saying the angel was the Devil in disguise and the verses were satanic rather than divine. Muhammad orders them expunged from Quran.

Persecution ended

This recantation pleased the Meccan elite, ending the persecution of the Muslims and confirming Muhammad’s acceptance. Later, the episode is treated as the Temptation of Muhammad.

“After that the monotheism of Islam, having been tested in the cauldron, remained unwavering and strong, in spite of persecution, exile and war,” Rushdie explains, “and before long the Prophet had victory over his enemies and the new faith spread like a conquering fire across the world.”

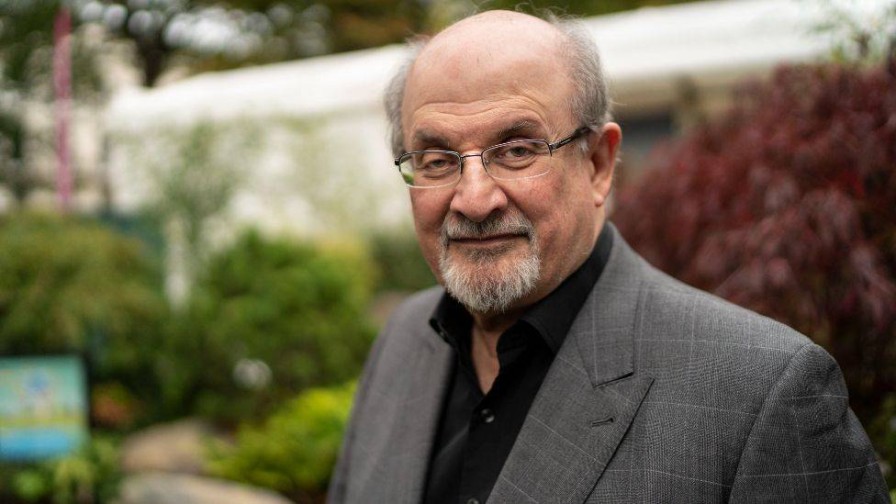

Salman Rushdie’s status is secure as one of the world’s greatest writers.

Today, Rushdie’s status as one of the world’s greatest writers is secure, though his novels and writings have not matched the acclaim of Midnight’s Children, a fantastical story about the switching of two newborns on the night of the ill-fated partition of India into Muslim and non-Muslim entities.

His latest, Quichotte (2019), is a typically dense tale, inspired by Don Quixote, by the 17th century Spanish writer Cervantes, and set in modern America. The titular character is a pharmaceutical salesman in a novel being written by another Indian migrant, who also produces spy thrillers, called Five Eyes, after the intelligence network.

At one point he wonders why the five nations involved mistrust each other. New Zealand is not trusted because the Kiwis “had never come up with a single useful surveillance programme”.

The attack on Rushdie, by a radicalised young Lebanese-American who wasn’t born when the fatwa was announced, will revive many of the negative aspects of Islam as viewed in tolerant Western societies. It will certainly weaken efforts by local Muslims to make criticism of their faith a hate crime.

Joseph Anton: A memoir and Quichotte, by Salman Rushdie (Jonathan Cape).

Nevil Gibson is a former editor at large for NBR. He has contributed film and book reviews to various publications.

This is supplied content and not paid for by NBR.