Rugby league’s journey to the mainstream

Social historian tracks fortunes of football’s outsiders.

WATCH: NBR columnist Nevil Gibson speaks with Calida Stuart-Menteath.

Social historian tracks fortunes of football’s outsiders.

WATCH: NBR columnist Nevil Gibson speaks with Calida Stuart-Menteath.

The Warriors are the only face of rugby league that most New Zealanders recognise. Yet the team is not part of a sporting competition that is representative of this country. That team is called the Kiwis, who are lucky to have any more profile than, say, national hockey or soccer teams when they are in an international tournament.

The burgeoning of professional sport in the past three decades upended sporting traditions that had served the country for up to a century. Privately owned teams – like the Warriors, the Breakers in basketball, and the Phoenix in football – are now part of Australian-focused enterprises.

Sports commentary is never short of debating whether these trends are positive or negative. The positives have benefitted elite players, who no longer must move to Australia, and television audiences, who can watch the best these competitions can offer.

The negatives are mainly at the grassroots: declining attendances for fixtures at club and provincial levels, lack of opportunities for all but the best players, and a loss of community involvement.

Ryan Bodman.

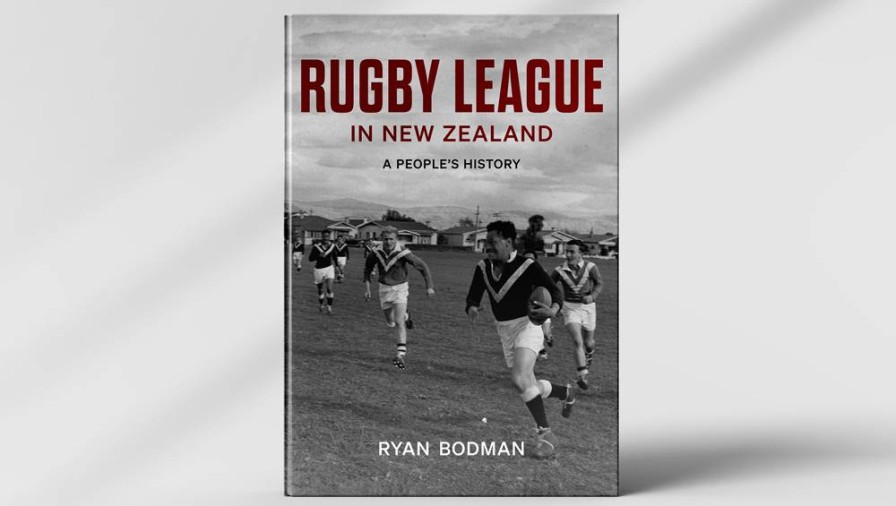

This has been felt more acutely in rugby league than in other codes, argues University of Auckland history graduate Ryan Bodman in his first book, Rugby League in New Zealand. It is subtitled as a “people’s history” to distinguish it from a retelling of great matches from the past. He suggests this socio-economic approach, better known as Marxist, would also suit unwritten histories of other strong affinity groups in pursuits such as stock cars, professional wrestling, boxing, silver and brass bands, softball, and netball.

Rugby suits this class-based analysis because of its bourgeois beginnings at the eponymous English public (ie, private) school in 1845. This was followed by a club preferring Rugby School’s rules over those of the Football Association, when it codified the sport also known as soccer in 1863.

This banned Rugby’s innovations such as running with the ball. The Rugby Football Union was formed in 1871, by which time international matches were being played in the ‘Four nations’ of Great Britain and Ireland. Rugby was also exported to the world as the British Empire expanded.

In New Zealand, rugby thrived after an initial match between Nelson College and the Nelson Football Club in 1870. By 1895, 17 provincial unions made up the national union. In that same year, the Northern Union, based in the heavily industrialised and mining counties of England, broke away from the national organisation over the issue of player payments to compensate for the loss of wages.

This schism was economic – as labouring workers had more to lose than middle-class amateurs – rather than one of different rules. Before the turn of the century, international tours lasting for months had become popular but were impossible for players on low wages and with families to support.

The first official All Blacks’ highly successful 1905 tour of Great Britain and Ireland prompted an enterprising postal worker, Arthur Baskerville, to organise a team to tour the Northern Union Football clubs under their rules of no wing forwards and play-the-ball tackles.

He recruited four players from the 1905 All Blacks, ignored the negative views of leading newspapers, and the team set sail in 1907. The All Golds, as they were disparagingly known, played 50 games, including some in Australia. Baskerville died of pneumonia in Sydney before the team returned. But his legacy endured as the first match under the Northern rules was played as a fund-raiser at Wellington’s Athletic Park.

In 1910, enough rugby players had switched codes to form the New Zealand Rugby League, which staged overseas tours in 1908 and 1909 with Māori teams. Racial discrimination, as well as the player payment system, made league attractive to Waikato Māori.

Rugby union administrators did not take the league challenge lying down. An attempt to introduce league at the Stoke Industrial School, originally a notorious Catholic boys’ orphanage near Nelson, was successfully resisted by the local rugby union in 1911. The school’s scandalous background helped bring this story to national attention.

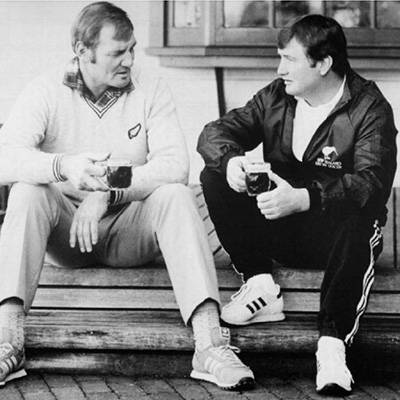

Kiwis’ coach Graeme Lowe, right, and All Blacks’ coach Brian Lochore.

League was on the back foot during the two World Wars, surviving in the industrial centres of Auckland, Christchurch, and Hutt, as well as the Waikato and West Coast mining areas. Religious prejudice was added to racial discrimination as a lure for league. Irish Catholic immigrants also boosted the cause of socialism, trade unions, and the Labour Party.

Marist clubs in Christchurch, Dunedin, and Greymouth resigned amid claims of bias, while Labour politicians – such as Paddy Webb, Pat Hickey, Michael Savage, the maverick John A Lee, Peter Fraser and Walter Nash – were all league stalwarts. The close ties with the political Left continued after 1945, with trade unionists Tom Skinner, Jim Knox, and Bill Andersen all taking roles as patrons, administrators, and coaches during the peak of their power in the 1970s and 1980s.

They were followed by David Lange and Sir Roger Douglas, due to their location in league’s heartland of South Auckland. Helen Clark’s lack of interest in sport did not extend to league. Bodman’s account of league’s political associations has appeal to the general reader, though some might jib at his rants about the impact of the neo-liberal reforms on working class families.

The early ties with the Kīngitanga (Māori King Movement) in the 1930s were boosted by a colour bar that prevented top Māori players from playing for the All Blacks against the Springboks until the 1980s. The popularity of league spread to freezing works in Northland, Taranaki, and Hawke’s Bay, resulting in an inter-provincial Māori competition for the Waitangi Shield.

Rugby union’s player bans were lifted during World War II, allowing easier changes of code. The most famous Māori rugby player of the 1930s, George Nepia, switched to league in 1937 while playing in England. Bob Scott played league as a boy before becoming the All Blacks’ legendary fullback and goalkicker.

The professional era arrived with live TV broadcasts in the 1990s to change both codes dramatically. Bodman’s account has little sympathy for the embrace of corporatism and its rich pickings for elite players and administrators from broadcasting rights and generous sponsorship.

The watershed of March 10, 1995, was “a break with the past”. The launch of the Warriors into an expanded Winfield Shield ceded control to the Australians. Rugby league moved into a new era where top talent and TV audiences reigned supreme. All Blacks such as John Gallagher and Matthew Ridge came across, playing in Australia and England.

Wainuiomata’s Ken Laban lifts the Lion Red Cup .

At the same time, the dominant code was also on a roll with the launch of Super Rugby in 1992. Opposition to the Warriors from diehard fans who saw dangers to the club game was offset by setting up a national championship, playing for the Lion Red Cup. But that failed after just three years.

Corporate manoeuvring, poor management, and a clash of Australia’s media barons split loyalties as the Warriors were sold to a consortium of private owners (Graham Lowe and Malcolm Boyle) and Waikato-Tainui, before ending up with businessman Eric Watson. The Australian broadcasters’ feud ended in 1998 with a merged National Rugby League including the Warriors. Ownership changed again in 2018 and 2020 when Autex Industries took full control.

The women’s national representative rugby league team had its start in 1995.

The past season was highly successful for the Warriors, with the adopted slogan ‘Up the Wahs’ being one of the year’s most memorable. Crowds were stronger than for Auckland’s Blues rugby team, underlying the critical role the Warriors play in keeping league viable.

Latest comments from the Warriors camp, published this week, indicated further moves for age-group teams to encourage promising players to stay in New Zealand rather than be picked off by the Australian clubs. But none of this reduces the social threat to other facets Bodman describes, such as the cultural ties and community identity for Māori and Pacific Islanders, the role of women in social activities (and increasingly as players), and the positive contributions of some gangs.

Though produced in coffee table format, with a lavish spread of photographs, the 300 pages of text contain too much overlapping material. However, the 50 pages of source notes and bibliography and index make a valuable addition to the publisher’s excellent record of high-quality history books.

Rugby League in New Zealand: A people’s history, by Ryan Bodman (Bridget Williams Books).

Nevil Gibson is a former editor at large for NBR. He has contributed film and book reviews to various publications.

This is supplied content and not paid for by NBR.