Robes and rules: A top judge's life in the law

Sir Kenneth Keith's memoir resembles a lecture series on his versatile expertise.

Sir Kenneth Keith's memoir resembles a lecture series on his versatile expertise.

The role of North American intellectual trends on New Zealand’s economic, social and cultural practices are greater than is generally recognised. While it’s obvious in fashion, entertainment and business, it is less so in the areas where you might expect dominance from the colonial power.

The biggest of these is the legal system, and how it has been open to ideologies developed in American universities. The most radical of these is critical theory, originally based on ideas from the post-modernist European Frankfurt school of Marxism.

This has been applied to social justice, racial, and gender issues by creating victim classes in a capitalist society run by a privileged elite, usually labelled as patriarchal. Critical theory is the standard form of discourse in many disciplines and has been absorbed into the public service, including the judiciary.

My conclusion is based on recent books about the law, not normally a topic that interests those on the sidelines. In the days when university study was limited to the few, the brightest headed overseas for doctorates and advanced degrees.

Some came home, bringing new ideas with them. Those who went to America made the biggest impact. For example, Sir David Williams KC, who attended Harvard Law School in the late 1960s, realised the courts could be used to fight environmental issues.

He was inspired by the US Environmental Defense Fund, which had successfully campaigned to ban DDT. In 1971, he helped set up the New Zealand version, the Environmental Defence Society. It was equally successful in challenging many developments over the past 50 years. (Its story is told by Raewyn Peart in Environmental Defenders, reviewed here.)

Sir Kenneth Keith at the International Court of Justice, 2006.

Williams went on to a distinguished career as an international arbitrator, a judge of the High Court, chief justice of the Cook Islands, and a law professor.

Also at Harvard during that time was Sir Kenneth Keith KC, who contributed to the Sir Geoffrey Palmer tribute volume, The Futures of Democracy, Law and Government, published last month and reviewed here.

In it, Keith described how he and close colleague Palmer changed their minds on a Bill of Rights, which became law in 1990. It was a fundamental switch from the British system of parliamentary sovereignty to one based on American constitutional law that limited those powers.

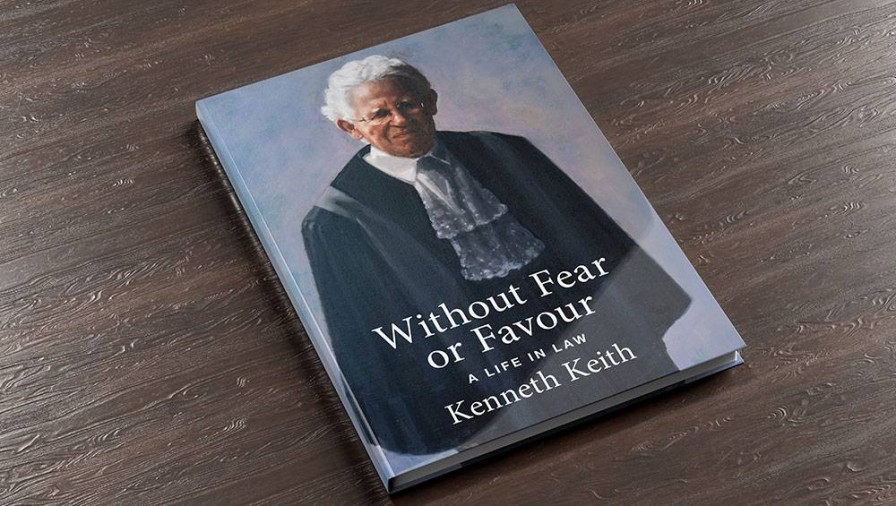

Now, Victoria University’s publisher has released Keith’s own memoir, Without Fear or Favour, a substantial volume that covers his involvement in a wide range of legal interests since he started as a clerk in a magistrate’s court. The chapters are topic-based and resemble a series of lectures on Keith’s many interests – probably the widest for a non-politician of any New Zealand judicial figure.

When he retired in 2023, Keith had been a member judge of the International Court of Justice; the Privy Council and its replacement, the Supreme Court; the Court of Appeal; and the High Court. His academic connections were with the Victoria Law School, where he is a professor emeritus, and he was president of the Law Commission, a body devoted to law reform.

The latter was one of his passions, as well as international law, which gave him early career opportunities in the Department of External Affairs, the United Nations Secretariat and as director of the independent NZ Institute of International Affairs.

The American influence on international law began after World War I with the President Woodrow Wilson-backed League of Nations and its successor, the UN, of which New Zealand was an enthusiastic founder.

The International Court of Justice bench in 1974 hearing New Zealand’s case against French nuclear testing.

Keith notes that lawyers in private practice had little need to be aware of international law in the past, but this has changed since the 1970s. Issues such as climate change, pandemics, international terrorism, refugee flows, humanitarian crises, and international trade are commonplace in the courts.

Yet international law was at play during the colonial era of the 19th century. Indeed, the Treaty of Waitangi was not an isolated document but was just one of several conceived and signed in the early 1800s.

In 1825, the British Crown, represented by the Governor-General of Sierra Leone, signed one with tribal kings in West Africa, known as the Sherbro Treaty after one of them. It, too, had three simple provisions that ceded sovereignty in return for the rights and privileges of British subjects.

The wording closely resembled that of the one signed at Waitangi 15 years later. These were not “cobbled together”, as some have suggested, and are not subordinate to translations into native languages. (In The English Text of the Treaty of Waitangi, reviewed here, Ned Fletcher reveals the careful preparation of the Colonial Office, which had far more experience in dealing with such matters than anyone else at the time.)

Keith also reminds us that it was politicians – not judges – who decided to backdate the Waitangi Tribunal’s purview to 1840, a move described by a judge and later president of the International Court of Justice, Rosalyn Higgins, as “one of the most radical social experiments of our time…”

Sir Kenneth Keith, back left, joined the International Court of Justice in 2006. President Rosalyn Higgins, the only woman, is in the front row.

Keith’s handling of this and other issues shows the importance of context as well as detail in deciding cases. This is how he sums up his philosophy: “One feature of good teaching, research and scholarly writing, of judging and reforming the law and the constitution, is the movement back and forth between particulars and generalities, or the facts (including legislative facts over time). Principles or standards may appear from the complexities of the details and may then be tested for their strength against those details.”

He goes on to illustrate this with a 1963 judgment, Ridge v Baldwin, by Lord Reid in a case concerning natural justice, following the dismissal of a chief constable without him being informed of the reasons or given a chance to defend himself.

The House of Lords overthrew a Court of Appeal decision that held natural justice did not apply to administrative decisions, in this example by a non-judicial body (the police).

Keith states how Reid’s decision “swept away much conceptual baggage” that was behind a common law decision made 30 years earlier. Reid’s ruling was initially negatively viewed by some New Zealand legal commentators. But given Reid had cited cases going back 400 years, the courts soon fell into line and firmly established natural justice as a core principle.

The change of mind on a Bill of Rights, mentioned earlier, is another example of Keith at his best in explaining the need for simplicity in the law and access to official information. The Bill was first proposed in the 1960s to complement several UN conventions of human rights.

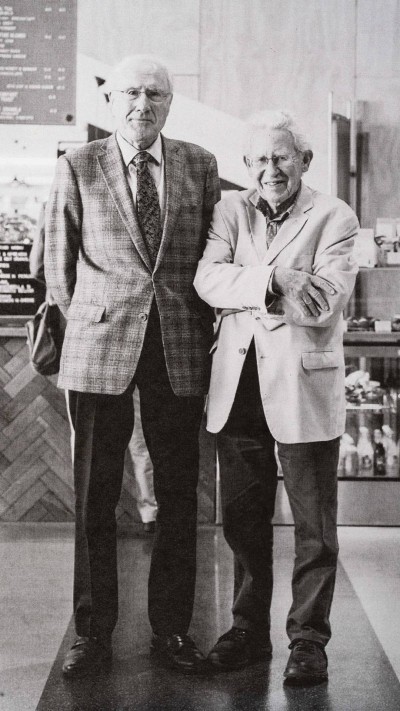

Close colleagues Sir Geoffrey Palmer and Sir Kenneth Keith.

At a series of public lectures, most speakers from the NZ Law Society and the Māori Council to academics and the Solicitor-General were opposed. Two, Richard Mulgan and Geoffrey Palmer, had recently returned from overseas study (Oxford and Chicago, respectively) to Victoria University’s political science department.

Among the grounds for opposition were that judges did not have the political legitimacy and were not experienced in the areas of law and policy that would arise. A key feature was that the courts could overturn legislation that breached stated rights.

Keith’s epiphany followed his studies at Harvard, where he learned about recent US Supreme Court cases where the courts could provide protection through a bill of rights. He participated in the drafting the eventual Bill of Rights Act, giving an insider’s view of how it evolved from a white paper prepared in 1985 by Palmer as Minister of Justice and passed into law when Palmer was Prime Minister in the final year of the Fourth Labour Government.

While this was the most controversial topic experienced during his career, Keith steers clear of being controversial by his practice of seeking the widest possible evidence and range of views. The National opposition voted against the Bill of Rights but would not dare to repeal it today even as the issue of judicial activism remains alive.

Keith states that New Zealand judges “had become more comfortable in making use of international material to gain a wider contextual view, especially when interpreting legislation”. He was among the leading practitioners of this, culminating in him serving a nine-year term on the International Court of Justice from 2006 to 2015.

He does not directly comment on trial cases he judged, but he does relate his time as a litigator when he was part of New Zealand’s case against French nuclear testing at the ICJ in 1974. Throughout, he maintains a detachment that is always outward-looking in justifying any course of action. It's a valuable legacy for someone who has lived a life in the law that encompasses more facets than perhaps any other New Zealander.

Without Fear or Favour: A life in the law, by Kenneth Keith (Te Herenga Waka University Press).

Nevil Gibson is a former editor-at-large for NBR. He has contributed film and book reviews to various publications.

This is supplied content and not commissioned or paid for by NBR.