Rare metals open door to mining’s new dawn

ANALYSIS: World struggles to supply essential minerals for ‘green’ technology.

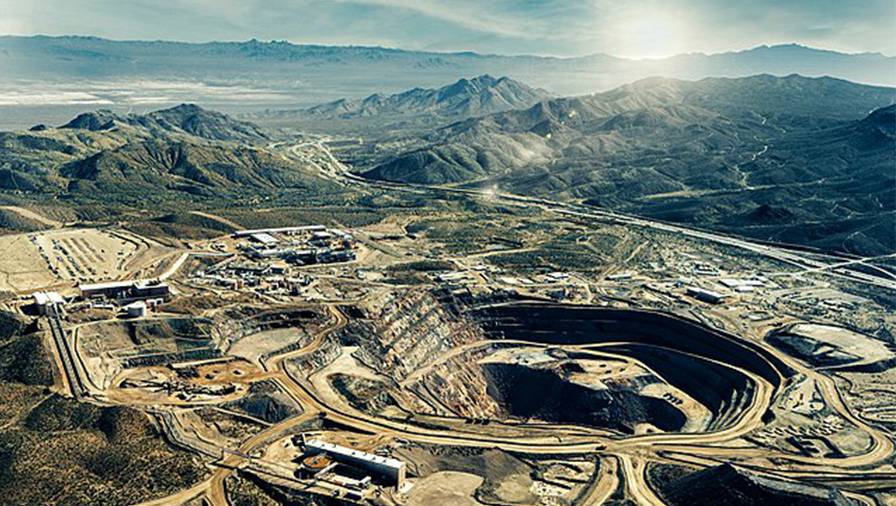

The Mountain Pass rare earths refinery at Mountain Pass, California, one of the few outside China.

ANALYSIS: World struggles to supply essential minerals for ‘green’ technology.

The Mountain Pass rare earths refinery at Mountain Pass, California, one of the few outside China.

New Zealand could be on the verge of another minerals-driven era of economic prosperity. Just as gold, coal and natural gas fuelled earlier ones, the next will be based on ‘green’ and digital technologies that depend on rare-earth elements.

A revival of the mining industry has always been the vision of Resources Minister Shane Jones, both in his times as a Labour cabinet minister and now a New Zealand First one in the coalition Government.

The release of the Draft Minerals Strategy on May 24 was a first but tentative step. In the global context, New Zealand is already well behind in supplying some of the essential ingredients of the transition away from fossil fuels.

The strategy paper is lean on detail and modest in a goal that doubles exports to $2 billion by 2035. It contains just one page on new opportunities, which include heavy mineral sands such as titanium, garnet and zircon used in metal alloys, abrasives, and electronic equipment.

Vanadium and titanium are used advanced iron and steel products, while antinomy is used in semi-conductors, micro-capacitators and retardants in batteries. In turn, the storage of energy requires lithium.

Antimony is closely associated with gold deposits and coal mining is a rich source of rare earth elements. Existing supplies of antimony are dominated by Russia and China. In fact, China has a virtual monopoly (80%) over the 17 rare earth elements on the Periodic Table. These have staggering electromagnetic, optical, catalytic, and chemical properties.

How this monopoly occurred, the damaging effects of pollution during processing, and the consequences of de-industrialisation in the West are core topics in The Rare Metals War, by French researcher and journalist Guillaume Pitron.

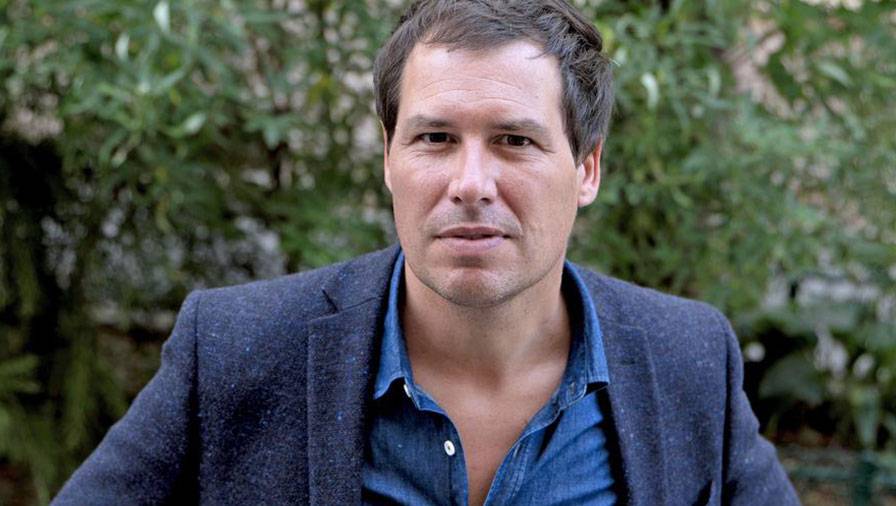

Guillaume Pitron.

The first edition, published in 2018, alerted the world to the political, economic, and social dangers of allowing the ‘green’ energy revolution to be in control of countries hostile to western democracies. The new edition is a rewrite based on five more years of research, including visits to mining sites in China, South Africa, North and South America.

Pitron’s aim is to expose the “dirty secret” of the highly polluting nature of extraction and refining rare metals. For example, the scale to obtain a kilogram of an element ranges from 8.5 tonnes of ore for vanadium up to 1200t for lutetium. Simply explained, these metals are turned into miniature magnets that create ‘green’ energy without carbon dioxide emissions.

Digital technologies then allow this power to be efficiently produced, stored, and distributed. Applications range from powering electric vehicles (EVs), solar panels and wind turbines to defence systems using precision missiles, fighter jets, and submarines.

Both rich and poor countries have endorsed decarbonised ‘green economies’ in climate change accords. Pitron argues this is fundamentally inconsistent with anti-mining campaigns because if oil, gas and coal fields are to be closed, they must be replaced by much more costly non-polluting mining techniques.

This point is not lost on Jones. In launching his report to a West Coast audience, he said: “Robust environmental protections and rehabilitation is business as usual for New Zealand’s operators – something that is considered and planned for every step of the way.”

The closed Globe Progress mine envisaged in 2030.

He cited OceanaGold, which has spent many millions on revegetation of the closed Globe Progress mine in Reefton’s Victoria Forest Park. This will be handed back to the community as a restored and enhanced asset.

Federation Mining’s Snowy River, near Ikamatua, also involves extensive environmental work and the establishment of passive water treatment ponds to ensure clean water is discharged.

A former adviser to the Labour government and ex-NBR journalist Vernon Small recently exposed the power if not the dishonesty of the anti-mining lobby: “…the previous government’s blanket ban [on mining in the conservation estate] was the result of a cock-up by Jacinda Ardern’s speech writer; the Government intended to leave the door open to some mining on stewardship land.

“The environmental lobby enthusiastically embraced the supposed ban, leaving the Government unable to go forward and unwilling to go back, condemning the issue to stasis by review for six years.”

Among the good news is that the US, France and other major mineral-producing countries signed a security pact in 2022 that aimed to reduce dependence on China. These countries included Bolivia, Peru and Chile for copper and lithium; India for titanium; Guinea and South Africa for bauxite, chromium, manganese and platinum; Indonesia for nickel and tin; and New Caledonia for nickel.

The riots in Noumea were partly due to the stress on western nickel producers by the Chinese, who typically undercut higher-cost operators to maintain their or increase their market share. Indigenous communities in many mineral-rich countries are keen to share in the spoils rather than remain banana (build absolutely nothing anywhere near anything) republics.

The Mountain Pass rare earths refinery at Mountain Pass, California, one of the few outside China.

In recent developments, the US said it was on track to establish a domestic rare earths supply chain to meet its defence needs by 2027. An OECD forum in Paris called out China and Myanmar for destructive and toxic practices in mining for dysprosium and terbium, which are essential for magnets in EVs and wind turbines.

China refines 68% of the world’s cobalt, 65% of nickel, and 60% of lithium for EV batteries, of which it is also the world’s leading producer. China’s advantages arise from controlling the entire production chain from mining raw materials in Africa, Myanmar and elsewhere through to its 90% ownership of the world’s processing capacity for rare metals.

That will need to change in the next decade with Pitron predicting production will need to double every 15 years. This means digging up more ore in the next 30 years than has been mined in the past 70,000 years. Demand for EV batteries alone will require 400 new mines for the basics, such as graphite, lithium, and nickel.

Pitron describes a Bastille Day meeting in 2016 hosted by French President Francois Hollande. New Zealand Prime Minister John Key attended, as did two “kings of the Pacific” – Filipo Katoa (since resigned) and Eufenio Takala of Wallis and Futuna.

The topic was the ‘great cauldron’ – a 20km volcanic crater said to contain a “priceless treasure trove” at the bottom of the Pacific Ocean, one of two final frontiers in the search for rare metals. France’s global maritime domain, thanks to its colonial territories, is the world’s biggest at 11.7 million sq m. So far, undersea mining for the likes of manganese nodules is in its infancy, though it has been touted for New Zealand over several decades.

An asteroid like this was valued at US$10 quintillion.

The other unexplored frontier is space, which is home to an equally vast source of rare minerals. A 2015 asteroid, known as UW-158, was estimated to contain 90m tonnes of platinum, worth some US$3.5 trillion. A more recent one, in 2021, was valued at a staggering US$10 quintillion (10,000 million trillion), more than the total global economy.

This a fact-filled book that should lighten the burden Jones carries in persuading his cabinet colleagues as well as the public to put the mining industry on steroids. The draft strategy timetable to 2040 is leisurely bureaucratic journey through data collection, funding opportunities and environment impact reports.

Pitron urges much greater urgency if the West is win the rare metals war with its commitment to high environmental and labour standards. Although it lacks an index, this book of less than 300 pages contains a 12-page bibliography, 28 pages of appendices and 45 of source notes.

The Rare Metals War, by Guillaume Pitron (updated edition). Translated by Bianca Jacobsohn (Scribe).

The Rare Metals War, by Guillaume Pitron (updated edition). Translated by Bianca Jacobsohn (Scribe).

Nevil Gibson is a former editor at large for NBR. He has contributed film and book reviews to various publications.

This is supplied content and not paid for by NBR.

Sign up to get the latest stories and insights delivered to your inbox – free, every day.