Polymath photographer; curious case of Kiwiana

ANALYSIS: Two curators explain pictures from New Zealand’s past.

Leslie Adkin: Farmer Photographer, by Athol McCredie, and Kiwi: A Curious Case of National Identity, by Richard Wolfe.

ANALYSIS: Two curators explain pictures from New Zealand’s past.

Leslie Adkin: Farmer Photographer, by Athol McCredie, and Kiwi: A Curious Case of National Identity, by Richard Wolfe.

The 17th century is known as the Age of Reason for laying the foundations of the modern world in business, science, medicine, philosophy, culture, and much else. It was an era when clever tradesmen made remarkable discoveries.

An example was Dutch drapery retailer Antonie van Leeuwenhoek, whose hobby of making lenses to view fabrics and threads led to the discovery of microbiology. While he forwarded his findings to the Royal Society in London and was elected as a member, he worked as an amateur completely outside the prevailing scientific system.

He inspired a tradition of practical polymaths such as Robert Hooke, Robert Boyle, naturalist Jan Swammerdam, and botanist Joan (Johan) Huydecoper. Isaac Newton, the most famous English scientist of his time, developed many of his early theories on calculus, optics, and the law of gravity while housebound on the family farm.

This ethos continued with European settlement in New Zealand. Samuel Butler farmed the Canterbury high country but also wrote extensively. He is best remembered for his satirical novels, including Erewhon, and his advocacy of Darwin’s theories of evolution.

George Leslie Adkin, known as Leslie, spent much of his life as a farmer near Levin but is recognised for his contribution to the sciences of geology, archaeology, and ethnology. His main interests were tramping in the nearby Tararua ranges and photography, which in the early 19th century was an expensive hobby.

Before Kodak’s invention of roll film in 1888, photography was largely a commercial business done in studios. Film popularised the snapshot but produced low-quality pictures. For that reason, serious photographers stuck with glass plates and tripod cameras until the 1930s.

The Adkin and Herd families at the wreck of the Hydrabad, Waitārere Beach, 1909.

Amateurs such as Adkin were rare. Photography was costly in time and resources. Six plates produced only 12 shots before a bulky camera could be reloaded under darkroom conditions. Each shot could take several minutes to prepare.

In 1911, aged 22, Adkin produced his first scientific paper, on the geology of the Ohau River, though he had no formal qualifications. During the 1920s and 1930s, he recorded numerous expeditions into the Tararuas, all illustrated with superb photographs that also made their way into the illustrated magazines of the day.

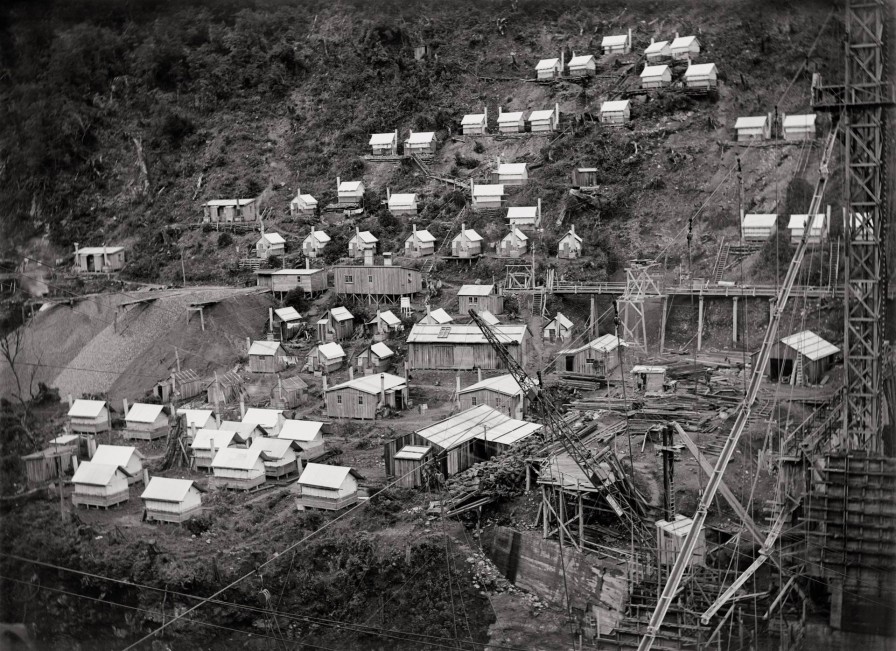

Among them was the construction of the Mangahao hydro dam from 1920 to 1924. It was a complex project, comprising two dams and three reservoirs with tunnels and pipelines covering 4.8km.

Mangahao dam workers’ huts, 1924

In 1929, Adkin’s photographs of Māori life for a local history book, Te Hekenga, attracted the interest of Elsdon Best, the country’s leading ethnologist. Best commissioned a more definitive work on the history of Māori places names in Horowhenua. This was published to great acclaim in 1948. A second book, The Great Harbour of Tara [Wellington], followed in 1959.

Adkin handed over his farm to his son Clyde in 1945 and moved with his wife Maud Herd to Wellington where he was employed at the then Geological Survey as a lowly paid palaeontologist’s assistant.

After his death in 1964, Adkin’s extensive trove of more than 6000 negatives and 200 Māori artefacts ended up at the Dominion Museum (now Te Papa). But it took several years before photography curator John Turner recognised the real treasure in Adkin’s carefully documented collection.

These were not his largely unpeopled landscapes but his private photographs of family life. Turner judged these as the country’s best examples of artistic personal images. A key feature was an informality that could not be matched in the studio photography that dominated the historical record up to World War II.

Maud Herd and Leslie Adkin, 1913. A string was used to trip the camera shutter.

Many featured accomplished musician and painter, Maud Herd, as muse and model. Their families were close friends, and Adkin tracked their joint outings before and after the couple married in 1915. Then came their children, Nancy and Clyde, growing up in a new generation. The pictures ranged from domestic chores, farming activity, cultural pursuits, and beach picnics, to community celebrations by both Pākehā and Māori.

The pictures were displayed in popular exhibitions held throughout the country. Adkin’s life was recorded in a biography, An Eye for Country (1997), by Anthony Dreaver.

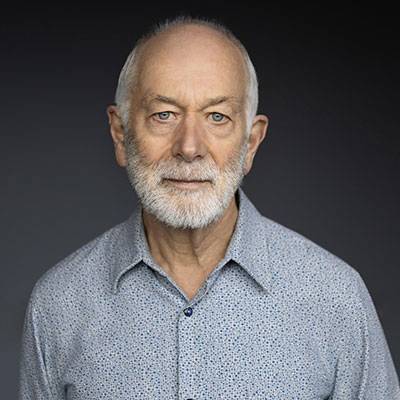

Te Papa curator of photography Athol McCredie.

Te Papa’s curator of photography, Athol McCredie (Brian Brake, 2010; New Zealand Photography Collected, 2015; and The New Photography, 2019), takes this a stage further in Leslie Adkin: Farmer Photographer. This remarkable, 244-page coffee table book showcases more than 150 photographs in stunning monotone detail, mostly from the private collection and not previously published.

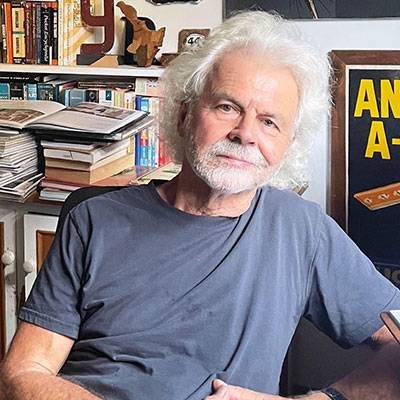

A more modest contribution to the coffee table genre is Richard Wolfe’s Kiwi: A Curious Case of National Identity. It, too, is the work of a museum curator (now a full-time author) and shows how hungry the early colonists were for knowledge about unique flora and fauna.

Among the first organised bodies to pursue the scientific tradition was the Auckland Mechanics’ Institute, established in 1841. Wolfe observes: “[P]ublic libraries, museums and other educational facilities [were] hallmarks of a civilised society.”

The institute sought books and specimens about this flightless bird, known for its nocturnal habits. But the first full post-mortem examination of a kiwi was published in a Wellington newspaper that same year, and the first live specimen, a female, was sent to London in 1851.

Richard Wolfe.

Already, the colony’s “most remarkable bird” was of great interest in London, where it was described as the remnant of a family of gigantic wingless birds that were “fast disappearing by the exterminating spread of the colonists”.

By 1840, half of New Zealand had been deforested by fire. The kiwi was also threatened by introduced predators, including rats from the Pacific Islands.

The story of how this unusual bird became a synonym for all citizens is a fascinating read. It was adopted by dozens of businesses in brand imagery and used to name ships, horses, sports teams, financial schemes, and even a prime minister (‘Kiwi’ Keith Holyoake).

The first ship called Kiwi was launched in 1849. Ten years later, another was an early client of New Zealand Insurance, which had a kiwi in its logo until 1987. BNZ put one on a banknote in 1898, the same year the Post Office issued a six-penny stamp. This was followed by the Reserve Bank’s one-pound note and two-shilling florin coin in 1934.

The first trademark using a kiwi was granted to drug company Kempthorne Prosser in 1877, by which time it had been applied to a range of household products, chemicals, and fertiliser. KP’s legal defence of its trademark until 1927 had kept the internationally marketed and Australian-made Kiwi shoe polish brand out of New Zealand, though the product was available under another name. Meanwhile, Kiwi polish sold in some 170 countries.

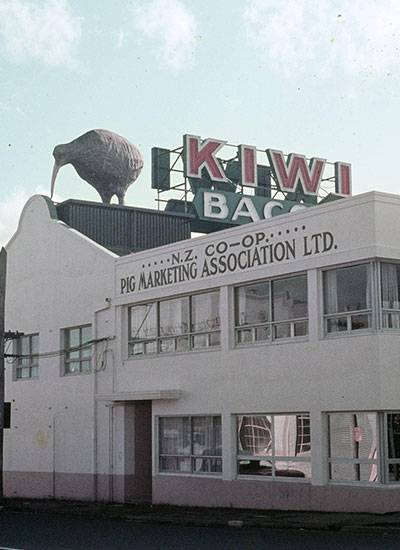

The Kiwi Bacon factory, Auckland,1980.

No longer protected, the kiwi became ubiquitous on every conceivable product used in homes, on farms, and in offices. One of the more unlikely associations was with bacon and ham. Giant kiwi models adorned five factories owned by the NZ Co-operative Pig Marketing Association, photo here courtesy of Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections.

The kiwi was embraced by troops in both world wars but was not officially part of the New Zealand Defence Force uniform until 1970. In the 1980s, the financial and business sectors chose the name ‘kiwi’ when the dollar was floated as a tradable currency. This was accompanied by a ‘kiwi’ share in the privatisation of Telecom (1987), the formation of Kiwibank (2001), a super scheme (2007), and the renationalisation of the railways (2008).

A whole chapter is devoted to the renaming of the Chinese gooseberry vine to kiwifruit by a horticultural company, and how it became a multi-billion-dollar export industry.

Wolfe once co-curated a ‘Kiwiana’ exhibition, a term he helped to invent. It now refers to the collection of objects and ways of doing things that became established during the periods of prosperity in the 1950s and 1960s.

Unfortunately, the eponymous bird hasn’t fared as well, despite sterling preservation efforts. Millions of kiwi populated these islands before human settlement. It’s now estimated the stable population is about 68,000. This compares with 26 million sheep and more than half a million registered dogs. While this book is an easy read, it is backed up by historical sources, bibliography, and index, making it one worth keeping.

Leslie Adkin: Farmer Photographer, by Athol McCredie (Te Papa Press).

Kiwi: A Curious Case of National Identity, by Richard Wolfe (Oratia Books).

Nevil Gibson is a former editor-at-large for NBR. He has contributed film and book reviews to various publications.

This is supplied content and not commissioned or paid for by NBR.

Sign up to get the latest stories and insights delivered to your inbox – free, every day.