Political games: Who’s the real threat to democracy?

Thriller points finger at New Zealand’s alt-right.

NBR columnist Nevil Gibson speaks with Calida Stuart-Menteath.

Thriller points finger at New Zealand’s alt-right.

NBR columnist Nevil Gibson speaks with Calida Stuart-Menteath.

Academic research has long proven election years in Western democracies bring out the worst in politicians. So far, this is holding true in this country as the official campaign approaches.

The politicians in power are making poor decisions without thought of the costly consequences. Those seeking power make outrageous claims on public credibility with promises they can’t, or won’t, fulfil.

I rechecked my 2020 review of Professor Garett Jones’s 10% Less Democracy – made just before that year’s general election – and found all its predictions came to pass. In fact, they were exceeded, as no-one expected Labour would win an outright majority.

In those pandemic years, the fears Jones held about politicians exercising too much power over the bureaucracy and the courts were exceeded. The result is that conditions are ripe today for a landslide defeat of 1975 or 1990 proportions.

In most democracies, these events would be excellent fodder for political novels. But New Zealand is an exception. The library shelf of such fiction is short. The landmark until this year’s blockbuster, Elizabeth Catton’s Birnam Wood, was CK Stead’s Smith’s Dream, published in 1971.

It caught the paranoia of the time: the war in Vietnam had energised the left against American efforts to hold back communist and nationalist rebellions; a conservative government led by Keith Holyoake was grappling with the first economic decline in two decades after the loss of guaranteed commodity markets in the UK and a global oil shock.

DVD cover of Sleeping Dogs (1977).

Stead’s response was that a right-wing populist, backed by American military might, would seize power. The novel’s adaptation into a movie, Sleeping Dogs, in 1977 proved a hit with its man-against-the-system plot while Robert Muldoon was hitting his stride as a red-baiting, pro-American populist.

In real life, a right-wing coup in New Zealand’s future was always going to be a myth. The opposite, a leftist over-reach of government power, was and still remains more likely. This is unexplored territory for New Zealand writers, the notable exceptions being Bob Jones’s satires of socialist fantasies in the early 2000s and an outlier, the anonymously written and published The Spin (1996).

(The talented literary sleuth Steve Braunias failed to solve the riddle, though his analysis suggests another talented writer, Simon Carr, who worked for Act in its earlier heyday and produced The Dark Art of Politics (1997), which had similar cover art to The Spin. Carr was also features editor at NBR before returning to the UK where he wrote parliamentary diary columns.)

These anti-socialist texts never became required reading in academic circles. Stead’s daughter Charlotte Grimshaw satirised the ruling class of the neoliberal years in several novels, notably Soon (2012), but they lacked the strong political content of their American and British equivalents.

The latest to join the fray is Riley Chance, a pseudonym for Roger McEwan, who has been a lecturer at Massey University and works as a part-time management consultant. He has an interest in the alt-right and its conspiracy theories that have thrived here since the Covid-19 pandemic and the Government’s response, with lockdowns and mandatory vaccination as a condition of employment by the state.

The Democracy Game is a thriller that melds recent events and real personalities with fictional characters and a fast-moving plot about a populist political movement backed by overseas money interests. The protagonist is a radical feminist journalist employed by Radio New Zealand in Palmerston North but whose agenda runs much wider than changing wire copy to fit a far-left perspective.

Palmerston North author Riley Chance.

Until I looked into the real identity of ‘Riley Chance’, I figured the author was female, as most of the story is told from the radio journalist’s view – that society’s biggest enemies are males in business who are “wealthy, arrogant, egocentric and dim”. These men are typically real estate agents and car dealers, who are dabbling in politics because they see a threat to private enterprise unless an alt-right organisation, ProtectNZ, gains political power. It can only do this if it has a charismatic leader who commands popular support.

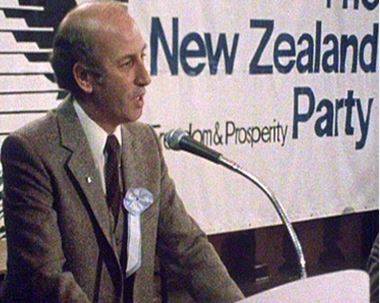

New Zealand Party leader Bob Jones in the 1984 election campaign. Source: TVNZ.

In the New Zealand context, that could be Jones’s New Zealand Party of the 1980s or, more recently, the clutch of groups that were present at the occupation of Parliament grounds in February 2022. However, we soon learn ProtectNZ is not a spontaneous reaction to unpopular political decisions.

Instead it is manipulated by foreign backers and a cabal of well-heeled men reminiscent of attempts by the Exclusive Brethren to influence Don Brash and the National Party.

Their first action occurs at a public rally where a Manchurian Candidate-style attack is made on the leader to elicit public sympathy. But the journalist, who witnesses the attack, digs deeper, helped by a genuine foreign element – a former US secret agent who is lying low in Golden Bay.

They spring the man who delivers letter box threats to the journalist’s home, and trace these actions back to the sinister forces behind ProtectNZ. Along the way, the journalist spouts her contempt for all things masculine, while the writer name drops examples of dodgy people, organisations, and superfluous explanations that are commonly produced by creative writing circles.

These pop up with intriguing inconsistency. A trio of leaders at the February 2022 parliamentary protest are referred to only by their surnames, as are Peter Thiel, Michael Bloomberg, and the Wright family, who sponsor Sean Plunket’s The Platform. Surnames only also apply to Trump adviser Steve Bannon and Putin’s ideological muse Aleksandr Dugin. Both are inaccurately described as “leering rich twats”. By contrast, full names are given to suicide cult leaders Jim Jones and David Koresh.

Hobson’s Pledge, the Free Speech Union, and The New Zealand Initiative are all referenced as akin to alt-right activists. This is the journalist’s advice on running an election campaign: “A subtler way is to use social media, scripted populist messages, marketing, and shitloads of money to convince people their way of life in under threat, that the media are evil, and mythical Tesla-driving greenies are the enemy.”

The problem, she goes on, is that the contest is rigged. “Trump did it in the US, Bolsonaro in Brazil, and dark money helped Brexit over the line. We think domestic terrorism is about the nutters shooting up mosques, and it is, but the same twisted alt-right hatred and money is lurking behind ProtectNZ.”

Surprisingly, this amazing display of naivety is told to a sympathetic SIS agent, who helps in the hunt for the villains. Such statements detract from some genuine page-turning action as the plot reaches its climax. Overall, this is a low bar for any thriller and ensures Catton is in no danger of being dislodged any time soon.

The Democracy Game, by Riley Chance (Copy Press Books).

Nevil Gibson is a former editor at large for NBR. He has contributed film and book reviews to various publications.

This is supplied content and not commissioned or paid for by NBR.

Sign up to get the latest stories and insights delivered to your inbox – free, every day.