Passionate about business? Don’t even think about it

Business school researchers give advice on what work’s best.

The Conversation on Work, edited by Ian O Williamson.

Business school researchers give advice on what work’s best.

The Conversation on Work, edited by Ian O Williamson.

There’s no end to the ingenuity of researchers seeking ways to improve the running of a business or organisation.

The Bartleby column in The Economist reached out to the late Dutch American primatologist Frans de Waal, who died last year. His books Chimpanzee Politics (1982) and Mama’s Last Hug (2019) are anthropomorphic studies that compare human and animal behaviour.

Bartleby quotes the latter book, revealing how animals signal submissiveness to their more powerful counterparts. Monkeys and apes use a teeth-baring grin as a signal of submissiveness. Hanuman langurs, a type of monkey, present their hindquarters.

“Spotted hyenas of both sexes (yes, both) have a habit of displaying erections to acknowledge that they sit lower down the pecking order. Chickens invented the very concept of pecking orders,” the column goes on, citing the office equivalent of everyone laughing at a joke by the most senior person in the room.

“Seen from a distance, it might look like the filming of a Netflix special. Inside the room, it’s much more likely to be a display of deference than an outbreak of genuine hilarity.

“The spotted hyena would not survive for long in most organisations. But patterns of deference and dominance are as natural for humans as they are for other animals, and the workplace is no exception.”

Spotted hyenas would not last long in most organisations.

The column goes on to explain the good and bad in hierarchies and why it is advisable, to keep your job, of being “alert to quietly submissive workplace behaviours”.

I mention this to illustrate the value of The Conversation on Work, part of a series linked to the global news website in which academics expose their research in op-ed-length articles suitable for newspapers.

New Zealand has its own The Conversation website, which like the others is edited by journalists to avoid academic jargon and obscure language.

The Conversation on Work comprises some 35 contributions from the United States website, though some of the authors are from European universities and, in one case, Australia’s CSIRO, a government science and research agency.

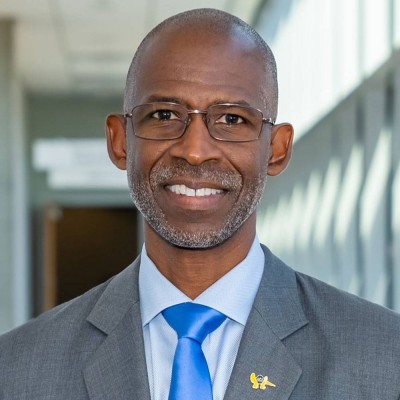

Ian O Williamson.

The book has no New Zealand content apart from its editor, Professor Ian O Williamson, having recently been a pro-vice-chancellor and dean of the Wellington School of Business and Government at Victoria University. He is now the dean of the Paul Merage School of Business at the University of California (Merage is an American billionaire who co-founded Chef America Inc).

Williamson groups the column-length essays under four headings: How work has changed; The workforce of the future; The future workplace; and Technology and work. He also writes a brief introduction to each section, suggesting major books on the topics mentioned.

In several cases, the contributors wrote those books. Williamson’s preface alone has 26 references to books and academic articles, indicating this small volume’s wide scope of the latest in business school research.

None specifically links human and animal behaviour, but advice is given on “workplace courage” – the art of whistleblowing: when to speak up against the boss and reasons why many are reluctant to do so.

Themes of change traced back to the disruptions of the Covid-19 pandemic run through many contributions. Perhaps too many, but this is because the columns are selected from a period when this was a major research topic.

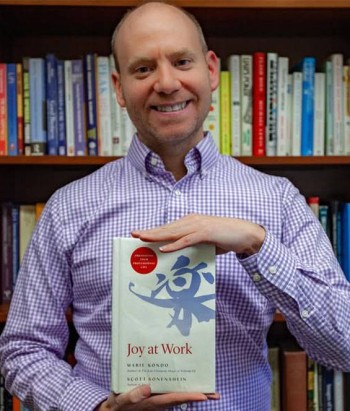

One reason is that the pandemic “accelerated a development that began years ago, when workers realised they needed to take more responsibility in directing their careers,” observes Scott Sonenshein, of Rice University in Texas and author of Joy at Work.

Scott Sonenshein.

Employees seized opportunities for greater job mobility and the freedom of remote work. “[A] new model is emerging that reflects concerns over a slowing economy and a more uncertain future,” Sonenstein continues, citing the rise of career port folioing.

This topic is examined in more detail by other contributors, including the need to acquire new and different skills as well as “side hustles” to boost incomes and reduce the risk of layoffs.

The ‘gig’ economy also gets a lot of attention, mainly for its ability to offer more control than ‘traditional’ jobs, though the downside is the lack of benefits. It must be emphasised that the research is mainly based on the American workplace, where employment law is more liberal, and the rewards for success are greater.

Some contributors are at what could be considered the woke-ist end of the spectrum, with an emphasis on sustainability and climate change issues; others critically examine the use of DEI (diversity, inclusion, and equity) training programmes as being counterproductive.

Instead, employers are urged to reject “talent blind” hiring and skills programmes in favour of ways that better recognise an individual’s worth. For potential employees, advice is offered on preparing CVs and online short-course programmes from reputable providers.

The author of The Trouble with Passion (2021) – Michigan University Associate Professor Erin Cech – warns of the dangers, urged by many entrepreneurs, in ‘following your dreams’. She argues the “passion principle” doesn’t necessarily lead to fulfilment.

Indeed, she argues, it’s one of the most powerful forces leading to overwork, mental breakdown, wage exploitation, inequality, and does more harm than good. Remember, this is based on research, not heroic thinking. New Zealanders were once labelled the ‘passionless’ people (by Gordon McLauchlan in his 1976 book), so maybe that will hold us in good stead.

Erin Cech.

And, following another topic in the book, and though New Zealand is not credited, the four-day week is given the thumbs up, thanks to its widespread adoption by Iceland for its benefits to work-life balance. NBR Lister Andrew Barnes is still spreading that word through 4 Day Week Global.

Related advice is given on ways to avoid burnout by managers and workers, and the benefits – in a world where remote and hybrid working is more common – of the “liminal space” of commuting as a break between work and home life. One researcher found that, even driving in congested traffic allows time to avoid thinking about work and other stresses, to focus on the immediate job at hand.

Modelling of the Los Angeles economy, before the fires, showed the impact of remote working. Companies were gravitating more to the centre, as office space and parking needs contracted, while workers would push out further into the suburbs.

House prices would therefore rise more in the outer areas, while rentals eased in the centre. This finding, applied to Auckland, could result in some different conclusions than current thinking.

One interesting topic is the impact of social activism in the workplace, recently an issue here on whether executives and workers should join the Treaty of Waitangi hikoi on company time.

In the US, employees make issues out of climate change, the use of software for military purposes, sports professionals protest about racism, and publishing house staff decide whether authors are acceptable.

Bhaskar Chakravorti.

Naturally, no book on the future of work can ignore the impact of technology, notably artificial intelligence (AI), which looms over a quarter of the contributions. But a historical perspective, from Tufts University’s Bhaskar Chakravorti, takes a sobering view on the productivity outcomes.

Advances – such as personal computers, the internet, and digitised word processing – have not delivered the same leaps forward as, say, electricity or the internal combustion engine. He notes the productivity surge in the second half of the 1990s from the worldwide web, and that from the Apple iPhone in 2007, have not been sustained.

Even the spurt from Zoom-style technology during the pandemic in 2020 has dissipated, he shows, as has the hype surrounding autonomous cars and pizza-making robots, not to mention AI replacing dozens of jobs.

Instead, he says: “It is safe to say that many of today’s predictions about AI technology’s impact on work and worker productivity will prove to be wrong”, as they have in the past.

But one thing isn’t likely to change, according to Thomas Kochan and Elisabeth Reynolds of MIT: “[I]ndustry leaders these days say they need tomorrow’s workforce to be filled with people who can think analytically and creatively, work well together in teams, and adapt readily to near-constant change.”

This has implications for business schools, as companies such as Amazon are imparting these skills internally to its own workforce, believing universities are still teaching skills designed for the previous industrial revolution.

The Conversation on Work, edited by Ian O Williamson (Johns Hopkins University Press).

Nevil Gibson is a former editor-at-large for NBR. He has contributed film and book reviews to various publications.

This is supplied content and not commissioned or paid for by NBR.

Sign up to get the latest stories and insights delivered to your inbox – free, every day.