Palmer’s law: There must be a better way

Scholars and colleagues pay tribute to our greatest modern-day lawmaker.

Scholars and colleagues pay tribute to our greatest modern-day lawmaker.

It is hard to believe many New Zealanders think their liberal democracy is in a state of crisis or decline. Real democracies, which first emerged in the 19th century, are rare and should be treasured by their fortunate citizens.

The Economist Intelligent Unit’s Democracy Index is due for its annual update. In 2024, it found while almost half of the world’s population live in a democracy of some sort, only 7.8% are in “full democracies”. More than a third (39.4%) live under authoritarian rule.

Two new democracies were recorded in 2023 – Paraguay and Papua New Guinea were upgraded from “hybrid regimes” to “flawed democracies”. The number of “full democracies” was unchanged at 24, with Greece being promoted while Chile fell out of this exclusive club.

It won’t be any surprise to hear that the top-three English-speaking countries are New Zealand (4), Canada (6) and Australia (9). All were founded by the British Empire, and their democratic ideals were embodied from the earliest days of colonisation.

The Freedom House Democracy Index ranks New Zealand at sixth, Canada 10th and Australia 11th. The only non-European country in the top 20 is Japan.

Citizens in other colonised continents were not so fortunate. Only two of the other 21 full democracies in the EIU index, Costa Rica and Uruguay, are not in Europe, which was home to the 19th century’s imperial powers. By the 1870s, all corners of the world were accessible by steamship and soon linked by undersea telegraphy cables.

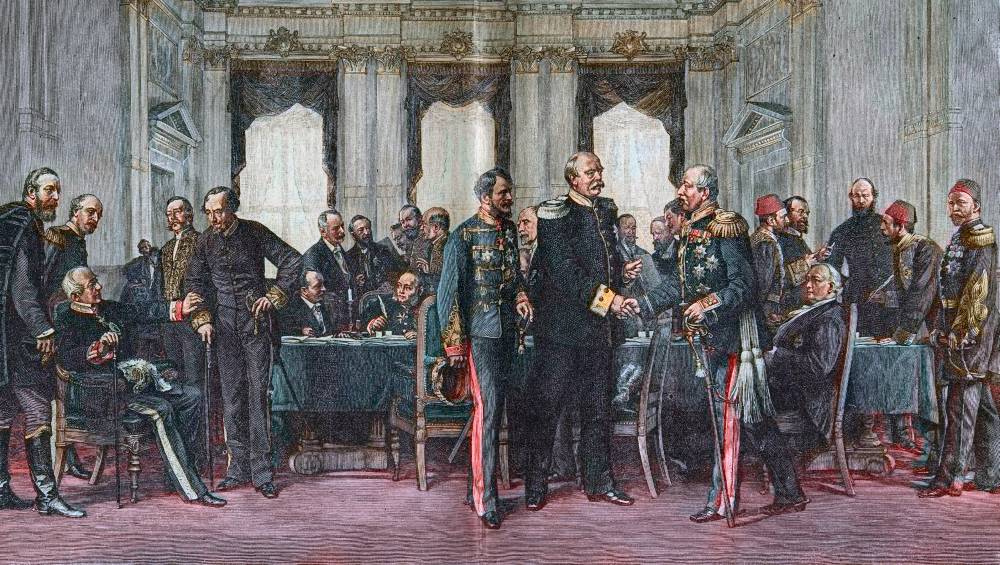

The opening of the Suez Canal brought the Indo-Pacific and Asia closer to Europe, boosting trade and commerce, as well as migration. Africa was carved up among the imperial powers at a conference in Berlin from 1884-85. But full democracy did not take root there, as it had in North America and Australia.

Artist's impression of Berlin Conference on Africa 1884-85.

Full democracies are characterised by their high scores in electoral process and pluralism, functioning of government, political participation, political culture, and civil liberties. They also have other qualities, best defined by Auckland academic Elizabeth Rata.

“‘Democracy’ gives us a system of parliamentary sovereignty, of law, of regulation. It recognises that our common humanity justifies equal rights. Those rights belong to the individual citizen, not to the group.

“The word ‘liberal’ gives us the freedom to be different – as individuals and in voluntary associations based on a range of shared interests – culture, heritage, language, sport, music, religion, politics, and so on.”

Liberal democracies are not perfect. The rush of titles on democracy’s flaws and ways to fix them is testament to continuing concerns. This column has reviewed some of them: Autocracy Inc, Liberalism and its Discontents, The Great Experiment, 10% Less Democracy, and The Good State. These were written by political analysts, historians and legal experts, not to mention, of course, practitioners in their autobiographies.

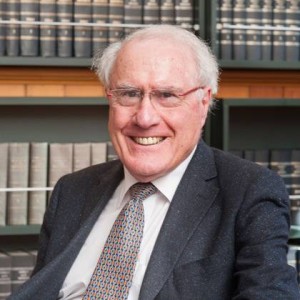

Sir Geoffrey Palmer.

The doyen of New Zealand experts is Sir Geoffrey Palmer, though he is by no means alone. He has recently become vociferous that “elections are not enough to ensure a peaceful and secure democracy”; and that steps be taken to “enhance the performance of democratic systems so that decisions affecting many people are made carefully, with more accountability and transparency”.

Palmer’s 12 suggestions should be well known; many have widespread support and won’t be listed here. They come with his unmatched experience as both an international expert on constitutional law and a politician who was responsible for some of the greatest rewriting of laws in any government.

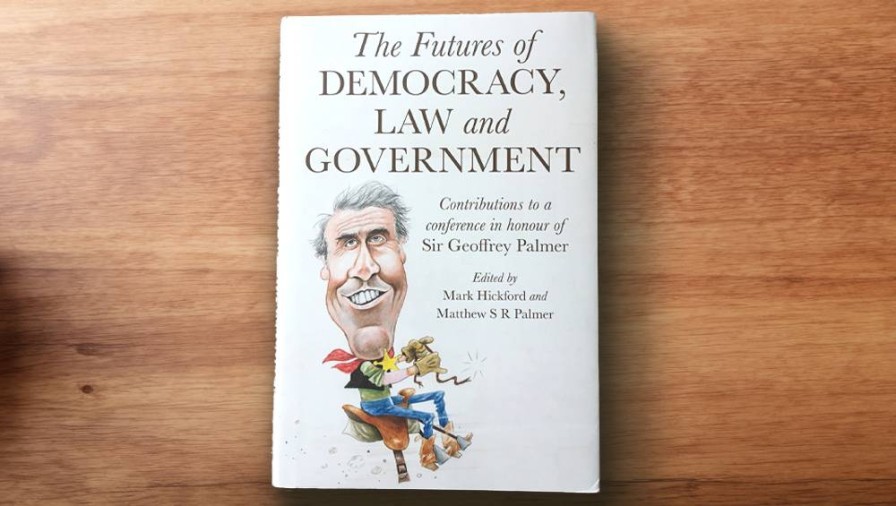

In October 2022, to mark his 80th year, Victoria University staged a conference at which scholars and colleagues paid tribute to his legacy. An edited version of proceedings is now available. The Futures of Democracy, Law and Government, edited by barrister Dr Mark Hickford and Palmer’s son, Justice Matthew Palmer, who was appointed a Judge of the High Court in 2015 and of the Court of Appeal in 2024. Both have long been associated with Victoria's law school at the level of dean and pro vice-chancellor.

The book comprises 13 contributions from well-known figures in politics, the public service and the law, as well as an introduction by the editors and a commentary by Sir Geoffrey himself.

This is a formidable volume that is copiously footnoted but is not beyond the reach of informed or interested readers. It covers five main topics: politics and policy, the Treaty of Waitangi, constitution and law, human rights, and international governance.

Sir Robert Muldoon.

Palmer summarises his views on democracy’s flaws by arguing the law should be superior to parliament, which can fall victim to the dictatorship of executive power (as it did under Sir Robert Muldoon). Generally, most MPs are incapable of handling big and bold reforms, made worse by the decline in standards of the public service and the Press Gallery, whose job is to hold the powerful to account.

The list goes on: “The adversarial politics that characterise the Westminster system is not adept at dealing with long-term issues beyond the next election.” In addition to my list above, Palmer provides a dozen titles on the decline of Western democracy and the failure of a rules-based system of international law.

His former colleagues in the Fourth Labour Government, David Caygill and Margaret Wilson, highlight the practical problems facing cabinet ministers and the implementation of party policies.

Wilson laments Labour’s embrace of neoliberalism against the will of party members, while Caygill relishes the challenge of attempting the impossible: the bottomless demands of the voting public for a health system that can never be fulfilled, or the inevitable tradeoff between the environment and the use of resources. His plea: “… the most urgent task of governments is to confront the public with the inexorability of their demands and essential need for difficult choices.”

Commissioner for the Environment Simon Upton.

Simon Upton, a former National minister and now Commissioner for the Environment, further describes the frustrations of protecting the environment while not crushing the hope of economic growth. He supports a second chamber to review legislation as select committees are incapable of the task.

Emeritus Professor Jonathan Boston again embarks on his crusade for a “managed retreat” to defeat rising sea levels based on modelling climate change into the next century. The cost of this social (and physical) engineering is beyond the fiscal resources of any government or society, as is the effort to reduce emissions.

In his erudite contribution, American law professor Jonathan Carlson contrasts the success of international cooperation to ban ozone-depleting gases with the failure of the climate change lobby. He blames this on the decision to put the costs of carbon emission reductions on only rich nations, while letting the majority off scot-free. “That lack of reciprocity fatally undermined the ability of Convention parties to negotiate any effective emissions-reduction agreement.”

Colin Keating, a diplomat, public servant and former Secretary of Justice, makes the most startling revelations by describing how he and a colleague at the UN signed New Zealand up for a series of international treaties without any serious debate among political parties or the public.

He considered, in the light of the 2022 occupation of Parliament grounds that had occurred earlier that year, New Zealanders had displayed “an excessive sense of individualism and an aggressive sense of entitlement [to] claim the shadow human rights without recognising the substance of them”.

Activist law professor Dr Claire Charters and legal historian Dr Alex Frame take differing sides over the Treaty of Waitangi, with the former backing the Waitangi Tribunal’s 2014 ruling that chiefs did not cede sovereignty to the British Crown. This widely believed claim is not based on evidence that would persuade a reputable historian such as Paul Moon.

Frame presents the historical context of sovereignty since 1840, including the emergence of a “third culture” to blend two peoples into a single nation. He also refers to a petition in 1883 that opposed the Treaty being subject to Parliament.

Chief Justice Dame Helen Winkelmann.

In her presentation on Palmer’s legacy, Chief Justice Dame Helen Winkelmann reveals that Māori feared the Treaty’s incorporation into a written constitution or Bill of Rights would make it a legal rather than political instrument.

Sir Kenneth Keith, a long-time colleague, confirms how the Bill of Rights resulted from Palmer changing his mind about the need for laws to limit the absolute powers of Parliament. A former student of Palmer’s, Professor Dean Knight of the Victoria law school, provides another perspective: that of Palmer as a communicator and teacher.

One of his recent books is a Survival Guide on civics, co-written with his grand-daughter, Gwen Palmer Steeds. In my experience, Palmer never rejected an argument with the media and was always available to put his case, though never as pithy as one might prefer.

For a time after leaving politics, Palmer co-founded a public law practice with Mai Chen, who calls for greater recognition of the growing diversity in the population. Barrister and author Jack Hodder (of The Capital Letter fame) notes “the tendency of senior judges to engage in conscious social engineering in interpreting legislation, changing the common law and deciding cases”.

His is a rare voice against that of Palmer’s, backed by a quote from Welsh jurist JAG (John) Griffith, who believes the law is no substitute for politics. “They [laws such as the Bill of Rights] merely pass political decisions out of the hands of politicians into the hands of judges or other persons.”

At $70 in hardback, this is a handsome volume that Palmer well deserves. It may not be as widely read as his other books, but it has valuable insights into how the intellectual legal mind works on issues that continue to be debated, albeit at a less rarefied and informed level.

The Futures of Democracy, Law and Government, edited by Mark Hickford and Matthew SR Palmer (Te Herenga Waka Press).

Nevil Gibson is a former editor-at-large for NBR. He has contributed film and book reviews to various publications.

This is supplied content and not commissioned or paid for by NBR.

Sign up to get the latest stories and insights delivered to your inbox – free, every day.