Pacific time: The past and future of Island nations

ANALYSIS: Historian examines colonial legacy of some of the world’s most dependent countries.

WATCH: NBR columnist Nevil Gibson speaks with Calida Stuart-Menteath.

ANALYSIS: Historian examines colonial legacy of some of the world’s most dependent countries.

WATCH: NBR columnist Nevil Gibson speaks with Calida Stuart-Menteath.

Seven of the world’s 15 most aid-dependent countries are islands in the Pacific. Research by the Lowy Institute, a think tank in Sydney, showed the region received more than US$40 billion in development assistance between 2008 and 2021, or an average of about US$3b a year.

It surged to a record US$4.8b in 2021, at the height of the pandemic, but was unevenly distributed. Papua New Guinea (PNG), which has 85% of the 14 island states’ population and accounts for 73% of the region’s GDP, gets about 43% of total funds.

The Solomon Islands receives 13%, and the rest (44%) is dispersed among the other 12. Per capita funding is highest in the micro-states of Niue, Palau, Tuvalu, and Nauru. The average Pacific economy receives about 14% of their GDP in loans and grants, the highest for any region in the world. This increases to 33% when PNG is excluded.

The trend is accelerating and has more than doubled since the US$2b total in 2008. The largest donor is Australia, followed at a distance by the Asian Development Bank, China, New Zealand, and Japan.

The pandemic was a major factor, but so are geopolitical pressures. China’s funding has eased back to focus on those it considers allies, while those who haven’t switched their diplomatic allegiances from Taiwan have benefitted from extra funding from other sources.

Since Lowy established the Pacific Aid Map, the upper middle-income countries (Fiji, Tonga, Marshall Islands, Palau, Tuvalu) have had steady increases, while the poorest (PNG, Solomon Islands, Vanuatu, Samoa, Micronesia, Kiribati) have had bigger spikes thanks to the entry of China. It has favoured the Solomons and Kiribati since they cut ties with Taiwan, but has generally pulled back its funding.

Despite being among the world’s most aid-dependent countries, the 14-nation bloc punches well above its weight in diplomatic clout, thanks to its votes in the UN. Climate change has enabled them to become ‘first recipients’ as existential victims of rising sea levels.

Leaders of the 14 Pacific Islands plus Australia, French Polynesia, New Caledonia and NZ at the 50th annual meeting in Tuvalu, 2019.

Though these claims have been challenged by some researchers, they have produced deals to guarantee migration or full relocation. Australia recently agreed with Tuvalu to take 280 people a year of its 11,000 population in a security pact. One condition was that Tuvalu maintained its recognition of Taiwan.

The US made a similar climate change and migration deal with Marshall Islanders, a third of whom already reside in America. The main reason for migration wasn’t primarily climate change, but opportunities in “education, health , work, and family connections,” according to a research unit.

The Pacific bloc’s diplomatic clout was also exercised in the UN by its opposition to a Jordanian-sponsored General Assembly resolution calling for an immediate ceasefire in Gaza on October 27. Six countries – Fiji, Marshall Islands, Micronesia, Nauru, PNG, and Tonga – voted ‘no’ along with 14 other nations, including the US and Israel. Palau abstained along with Kiribati, Tuvalu, and Vanuatu. Samoa did not cast a vote. Australia also abstained but New Zealand voted in favour.

The Lowy analysis concluded that climate-linked aid fell well short of estimated adaptation requirements and noted a “growing focus from donors on tackling gender inequality and empowering women”. In Fiji and PNG, rates of female participation in the labour force were roughly half that of men. Worse, UN reporting “suggests upwards of 60% of women and girls … have experienced violence at the hands of partners and family members”.

The World Bank says the average long-run GDP per capita would be 22% higher if the region’s gender employment gap was narrowed.

Surprisingly, New Zealand’s role in the region attracts little attention in the wider public debate. One eminent scholar with Samoan parents, Professor Damon Salesa, is among those who want this to change. He is vice-chancellor of AUT, having previously been an associate professor in Pacific studies.

Dr Damon Salesa.

He held a similar position at the University of Michigan after getting his first degrees at the University of Auckland and then as a Rhodes scholar at Oxford. Among his achievements was Racial Crossings (2012), based on his thesis about inter-racial marriage in the Victorian British Empire.

In 2017, when the Jacinda Ardern-led Labour Party was elected promising a better deal for all, including Pacific Islanders, Salesa wrote optimistically of New Zealand’s future as a Pacific-oriented country in Island Time. Islanders’ political representation, which was restricted to Labour, was greatly diminished at the last election compared with Māori, who have MPs in all main parties.

Salesa changes the focus to historical perspectives in his latest book, An Indigenous Ocean, which comprises 15 chapters. Most of them were previously published in academic journals. The language is less inclusive and framed in the culturally contentious method of “decolonisation”, which British historian Robert Tombs describes as a variant of anti-Westernism.

Tombs is one of a conservative group who have pushed back on the trend by Indigenous scholars to denigrate anticolonial nationalists such as Nehru and Jinnah, who wanted their countries to be modelled on modern democracies.

The ‘decolonisation’ project opposes the Enlightenment and values based in the democratic liberal tradition. In Island Time, Salesa points out New Zealand, as a one-time colonial power in the South Pacific, signed no treaty and gave “no special legal commitments or other guarantees for the rights, wellbeing, and support of Pacific peoples who live here [New Zealand]”.

In comparison with migrants from Asia and elsewhere, he notes: “Pacific people seem to suffer poorer outcomes more often than others, and to a degree that others don’t.” This occurs even “when policies and practices have specifically been designed to improve them [emphasis in the original].”

One reason was New Zealand’s practice, after it became a colonial power after World War I, to run its mini empire ‘on the cheap’. Apart from the salaries of unelected officials, places such as the Cook Islands were left to survive on a self-sufficient basis.

By contrast, Samoa, formerly a German colony based on a plantation economy, received more resources as mandated territory under the League of Nations. This period included the disastrous influenza outbreak in 1918 that killed thousands, and the fatal shooting of eight participants in a Mau a Pule protest march in 1929.

This parsimony was reflected in a reluctance for public works, and even public health, compared with New Zealand’s own rapid development in the inter-war period. This resulted from the differing objectives of a settler society and its needs. The colonial administrations were authoritarian and run along military lines with no aspirations to democracy.

World War II brought conflict among the major powers to the heart of the Pacific, with long-lasting effects. The introduction of Western products – “alcohol, firearms, gasoline, electricity, and condoms” – hit New Zealand’s little empire “like a combination of body blows”, according to Salesa.

Economically, the islands were more a burden than a benefit, due to the costs of remoteness and unreliable shipping. Unlike Britain, the market for imported consumer goods from New Zealand lacked scale, while attempts to develop export products and cash-crop economies were unsuccessful. In 2006, a trade balance in favour of New Zealand produced a surplus of more than $1b.

Salesa’s historical analysis is excellent and is little changed from when it first appeared in The New Oxford History of New Zealand (2009). Subsequent chapters cover a range of topics, notably the influence of the maritime environment and mass migration to New Zealand from the 1950s.

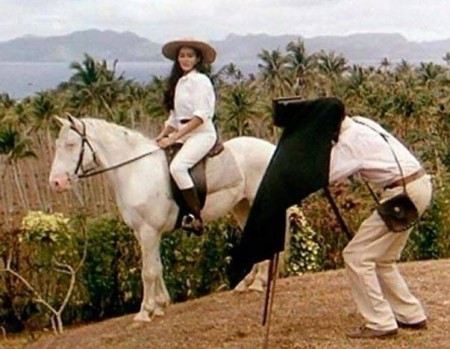

Barbara Carrers as ‘Queen Emma’ Coe in theAustralian-made TV

miniseries Queen of the South Seas (1988).

Some essays segue into historical anecdotes, such as the (now American) Samoan-born Coe sisters, Emma and Phebe, who used their commercial and linguistic skills to play crucial roles in German-controlled northern New Guinea before 1914. They were typical of ‘half-castes’, who had a distinct role in Samoa as intermediaries in the colonial administration.

The role of religion in Samoa demonstrated the merging of different beliefs and its continued cultural importance. “There was room within ancestral Samoan theologies for new gods, even an omnipotent new Atua [God]. There was room within Christian theologies, too, for the ancestral Samoan deities.”

Another segue examines the influence of Hollywood cowboys, particularly in the writings of Albert Wendt. “… their ready violence and masculinity, their music, their sense of romance and cosmic justice, were recognised … as transcendent figures.”

Not just in Samoa: a New Zealand example was played by Billy T James in the movie version of Came a Hot Friday (1985), though he was a figure of fun rather than the more serious proposition of a renegade with a potentially dangerous and mythical status. (The cowboy hat appears to be a fixture for some Te Pāti Māori MPs, too.)

These essays broaden our knowledge of some collective experiences of Pacific peoples that are usually overlooked in a general history. They are also a reason why this scholarly volume should reach a wider audience. It is also another of the publisher’s high-quality hardbacks with an index and extensive source notes, though regrettably no photos.

An Indigenous Ocean: Pacific essays, by Damon Salesa (Bridget Williams Books).

Island Time: New Zealand’s Pacific futures, by Damon Salesa (BWB Text, 2017).

Nevil Gibson is a former editor at large for NBR. He has contributed film and book reviews to various publications.

This is supplied content and not commissioned or paid for by NBR.