Other people’s money: exposing how frauds work

ANALYSIS: Investment analyst shows how honest commerce can be protected.

NBR columnist Nevil Gibson speaks with Calida Stuart-Menteath.

ANALYSIS: Investment analyst shows how honest commerce can be protected.

NBR columnist Nevil Gibson speaks with Calida Stuart-Menteath.

It may not be the world’s oldest profession but cheating and lying in regard to money is as old as the Bible.

Proverbs 21:23 warns, “Unequal weights and measures are an abomination unto the Lord.” Deuteronomy 25:13 recommends, “You shall not have in your bag differing weights, a large and a small.”

The first clear case of what would today be called commercial fraud, specifically a public procurement scam, is in the Second Book of Kings 12:4-8. King Jehoash tells the priests they can accept money on condition that they use it “to repair damages of the house [of the Lord] wherever any damage may be found. But it came about that in the 23rd year of King Jehoash that the priests had not repaired the damages of the house.”

In modern times, the history of fraud is usually associated with the rise of capitalism, accompanied by efforts to catch offenders and punish them. Wikipedia has listings for 40 types of fraud and their perpetrators have provided a colourful source for hundreds of books and movies.

Some of the latter will be on show on March 29 and 30 in Auckland at the NZ International Fraud Film Festival, sponsored by, among others, the Financial Markets Authority, Serious Fraud Office, a chartered accountancy firm and a law firm.

The aim, of course, is to educate the public, and those protecting them by enforcing the rules, to recognise a fraud by exposing recent examples of corruption, scams, forgeries, and cybercrime.

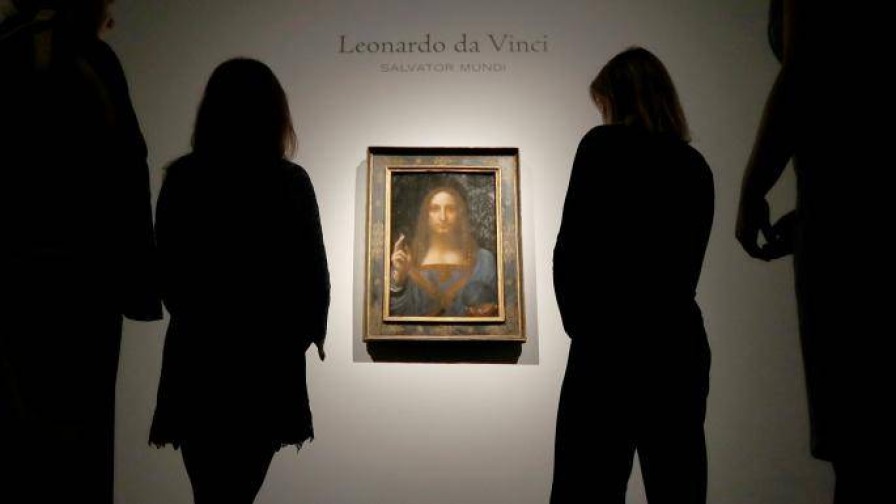

This work attributed to Leonardo da Vinci was touted as the most expensive artwork in history.

Though some titles have appeared in cinemas or on television and streaming services, others are screening for the first time. They include The Lost Leonardo (art forgery), China Hackers (cybercrime), The Talented Mr Rosenberg (dishonesty), Gaming Wall Street (corporate crime), and Nothing Lasts Forever (synthetic diamonds).

Most major frauds have provided the basis for feature movies and TV series. Among the best are The Wolf of Wall Street (Jordan Belfort), The Wizard of Lies (Bernie Madoff), The Big Short (Wall Street), Casino Jack (Jack Abramoff), Rogue Trader (Nick Leeson), Owning Mahowny (Canadian banker), and Catch Me If You Can (Frank Abagnale).

Seminal documentaries include Enron: The Smartest Guys in the Room, the long-running series American Greed and Fyre: The greatest Party That Never Happened. More recently, Netflix subscribers have had a choice of Inventing Anna (Anna Delvey), The Dropout (Elizabeth Holmes and Theranos), and The Laundromat (money laundering).

Most readers will be familiar with books on the most infamous frauds, both in New Zealand and overseas. Graeme Hunt’s Hustlers, Rogues & Bubble Boys: White-collar mischief in New Zealand (2001) is a good starting point for those seeking local content. (The NBR website also has 2903 references to stories on fraud dating back to 2010.)

For a wider view, Michael Levi’s scholarly The Phantom Capitalists (1981) and Regulating Fraud (1981) stand out, while each of the scam movies mentioned above have been based on at least one book, including self-serving ones written by the culprits themselves. Recent classics include Bad Blood by John Carreyrou, the Wall Street Journal reporter who exposed Theranos, and Billion Dollar Whale, by Tom Wright and Bradley Hope, also from the Wall Street Journal, on the Malaysian 1MBD scandal.

The book I’ve chosen this week is Lying for Money, by Dan Davies, an investment analyst and former banking regulation economist. His wide reading and personal experience combine to give a potted history of major frauds. Examples are explained in enough detail to make sense of his conclusions and recommendations without being bogged down in technical and legal language.

Elizabeth Holmes is the subject of a Netflix movie, The Dropout.

Among the most notorious are Ponzi schemes, the Great Salad Oil swindle, the Pigeon King International fraud, the fictional British colony of Poyais in South America, the Boston Ladies’ Deposit Company, the Portuguese Banknote Affair, Theranos, and the Bre-X goldmine scam. Personalities include some of those named above as well as Charles Keating, of US Savings and Loan fame, and Kray twins accountant Leslie Payne, who perfected invoices as a standover tactic.

Davies boils fraud down to four categories – “long firm” (obtaining false credit), counterfeiting, control fraud, and market crimes – that operate on the same basic principles. The only elements that change are the victims, the scammers, and the terminology.

He is more censorious than most in believing many commercial practices, such as private equity and share floats, are fraudulent by nature if not intent. He would take a hard look at the motives of the promoters of My Food Bag who sold their shares at $1.85 a couple years ago and are now worth just 25c.

He is more censorious than most in believing many commercial practices, such as private equity and share floats, are fraudulent by nature if not intent.

It’s nothing new for shares to lose such value so quickly. Shonky floats accounted for a sixth of all share floats on English stock exchanges from 1866-83 during the Victorian era. Cheats, fraudsters, and crooked bankers feature in the literary works of Dickens, Thackeray, and Trollope.

Jordan Belfort, the wolf of Wall Street, promoted worthless stocks.

Davies argues that Belfort, the promoter of worthless stocks, was jailed for breaking securities laws but his real crime was running a legitimate broking firm that facilitated companies going public when they had no likelihood of ever making a return.

Boom periods are usually end in a financial crash. “… fraud losses are dominated by large and rare occurrences [that] tend to come in waves, as a particular set of weaknesses … are found and exploited,” Davies states.

Then come the remedies, which are less about exploiting individuals’ greed and gullibility than spotting vulnerabilities in the system. “The controls and technologies of fraud prevention tend to move forward one disaster at a time.”

Dan Davies.

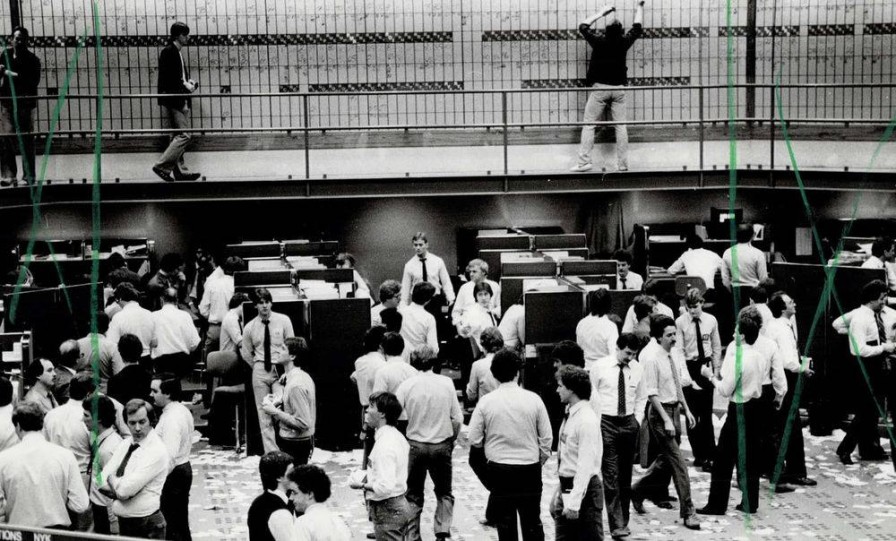

It’s not reassuring that largely honest and open societies are no better at resisting fraud than those considered less transparent and corrupt. Davies quotes the ‘Canadian paradox’ of a high-trust environment, where dishonesty is the rare exception rather than the rule. It was home to one of the world’s most notorious stock exchanges – mining shares listed in Vancouver – until it was shut down.

The Vancouver Stock Exchange, pictured in 1983, was notorious for its fake mining floats. Photo: Toronto Public Library.

This contrasts with the lack of defaults among Greek shipowners, where business is conducted among families without any resort to the law.

The high-trust model, of which New Zealand is an example, is often more open to a fraudulent activity due to a combination of complacency and lack of scepticism.

“There are very few other criminal acts where the victim not only consents to the criminal act, but voluntarily transfers the money or valuable goods to the criminal,” Davies writes.

This is the case with scams based on false promises, an intention not to pay for goods or services supplied, or a lack of official scrutiny or certification.

In his summary, Davies rejects the notion that fraud is a victimless crime. The usual outcome is that honest suppliers are bankrupted, lifetime savings are stolen, and vulnerable affinity groups or communities are torn apart.

He also finds the oft-quoted ‘fraud triangle’ of need (for money), opportunity (weak control systems) and rationalisation (explaining the need) lacking; it should be fleshed out with greater suspicion of any proposal based on fast growth and high returns.

Lying for Money: How legendary frauds reveal the workings of our world, by Dan Davies (Profile Books)

Further information: The NZ International Fraud Film Festival.

Nevil Gibson is a former editor at large for NBR. He has contributed film and book reviews to various publications.

This is supplied content and not paid for by NBR.