Orwell, the sniff test, and fake news

ANALYSIS: The life of a man who got up everyone’s nose.

NBR columnist Nevil Gibson speaks with Calida Stuart-Menteath.

ANALYSIS: The life of a man who got up everyone’s nose.

NBR columnist Nevil Gibson speaks with Calida Stuart-Menteath.

The ‘sniff test’ is a favourite tool for journalists wanting to throw doubt on the veracity of statements, claims, and policies, especially ones they don’t like.

It was used by former prime minister Dame Jacinda Ardern when it was revealed Air New Zealand was, legitimately, doing some engine repairs for the Saudi Navy. Others have applied it to Three Waters and other government policies that override traditional notions of democracy.

Journalists fall into the trap of failing this test when they publish one-sided accounts that blame the Government, big business, or someone else for a person’s plight when it’s mainly their fault.

‘Fake news’ should not pass the sniff test; so much so that governments here, near, and everywhere else want to ban it, or at least set up a body to look for it.

A proposed Australian Communications and Media Authority wants to hold Google, Facebook, and TikTok, among others, to account for spreading fake news in the form of misinformation or disinformation when it may cause serious harm. Something similar is being planned for New Zealand. So far, it has been strongly resisted by the Free Speech Union.

Readers shouldn’t need to be told the difference between these two types of harmful information. It used to be known as propaganda and, during the Cold War, those who lived the West knew it when they saw it.

One reason was George Orwell, whose ability to sniff out fake news was unmatched. But – unlike governments, who were the main offenders at twisting language and words to mean their opposite – Orwell called them out.

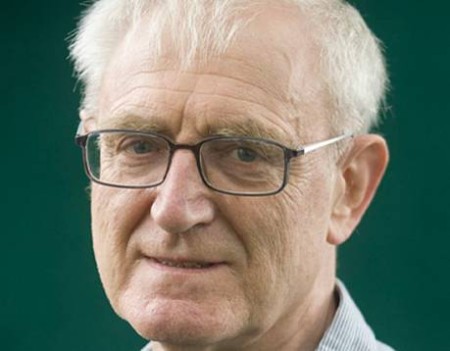

Professor John Sutherland.

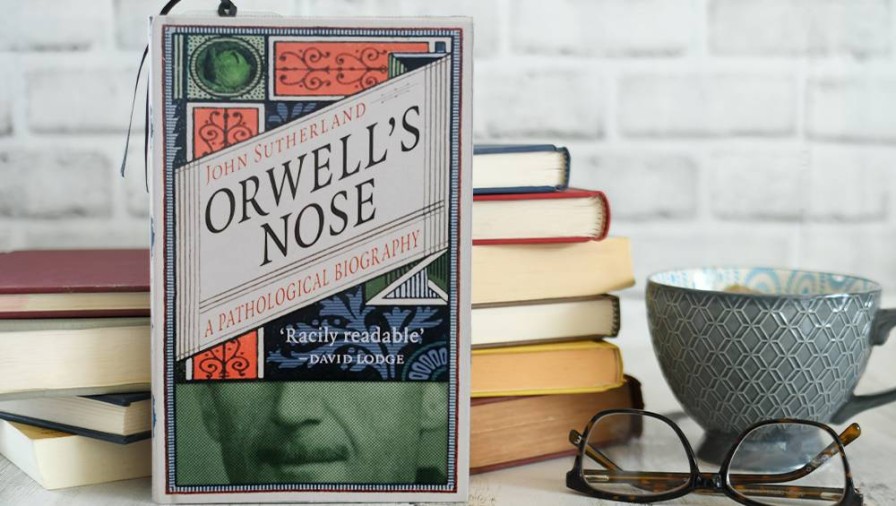

Which brings me to Professor John Sutherland’s Orwell’s Nose, a small but perfectly formed book that came out a few years ago without much publicity. In fact, books on Orwell keeping coming more than 70 years after his death in 1950.

This year alone, the Orwell industry has produced DJ Taylor’s Orwell: The New Life, a revised version of his Orwell: The Life (2003), the largest and most definitive of at least seven biographies; Masha Karp’s Orwell and Russia; and Anna Funder’s Wifedom, about Orwell’s treatment of his first wife, Eileen Blair (née O’Shaughnessy, later Orwell).

Karp sheds light on how Orwell’s ideas of totalitarianism took root in Russia and remain there today. Funder’s focus is on Orwell’s misogyny and its impact on Eileen. Though based on Eileen’s letters to a friend, much of it is fictionalised and does little to burnish Orwell’s reputation as a person.

Misogyny is not an uncommon trait among male writers in recent history. The German dramatist Bertolt Brecht, also a fervent socialist, was infamous for claiming the work of his female partners as his own.

Orwell married Eileen in 1936 (having dropped his real name of Eric Blair) and together they went to Spain during the civil war. She ensured his survival after a near-death experience and a convalescence that included a trip to Morocco and a spell in a sanitorium for TB patients. This period produced Homage to Catalonia (1938) and Coming Up for Air (1939).

The characters in Orwell’s earlier works were thinly disguised versions of his family life and experiences at preparatory school and Eton. He showed little gratitude for both, though his parents and sisters sacrificed a lot for him to attend the UK’s most expensive school. Orwell never lost his Etonian connections, which proved valuable for the rest of his life.

Sutherland attributes the “vein of nastiness” in Orwell’s fiction to the rejection by poet and publisher TS Eliot of Down and Out in Paris and London (1933), which was written in 1928. Burmese Days, based on his brief colonial service in the late 1920s, appeared in 1934, followed by A Clergyman’s Daughter in 1935. Orwell later regretted this latter novel, which was based on events 10 years earlier.

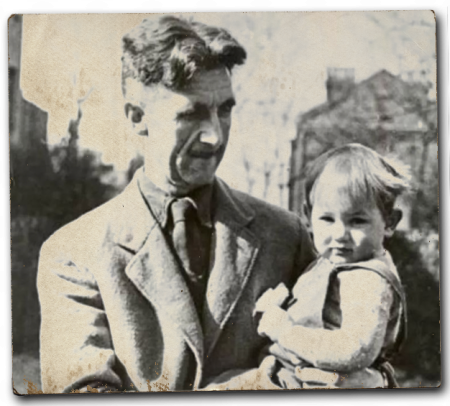

George Orwell with adopted son Richard in late 1940s.

Eileen was more ideological than Orwell, strongly supported the radical socialism of the Independent Labour Party, and is credited with sharpening his literary style. They adopted a son, Richard (later cared for by Orwell’s older sister Avril), but Eileen died a year later during surgery in 1945. By this time Orwell had become one of Britain’s foremost wartime intellectuals.

He worked for two years as a talks producer for the Indian Service of the BBC from 1941-43, and was literary editor of The Tribune, the most prominent left-wing journal of the 1940s. Lord David Astor, who like Orwell was an Etonian, engaged him as a freelance contributor to The Observer, a Sunday paper that was Britain’s leading Liberal and anti-establishment voice in the 1950s.

But his continued ill health, heavy smoking and drinking, notorious private life, and offensive body odour did not make him any more popular than Animal Farm was with his usual publishers, who were still under the influence of the Soviet Union’s sacrifices during World War II.

When Animal Farm, a savage parody of Stalinist Russia and socialist totalitarianism, was finally published in 1946 it became an instant hit, particularly in the US, at the beginning of what became the Cold War, a term Orwell had coined.

Sonia Orwell (née Brownell), left, in the offices of Horizon magazine (1950s).

Another formidable intellectual, Sonia Brownell, was Orwell’s next mistress, but not exclusively, as she also had affairs with many French philosophers. They married in 1949 just months before Orwell’s lack of concern for his health finally claimed him in 1950, aged 46.

In his racy account of these final years, when Orwell sealed his fame with Nineteen Eighty-Four, published shortly before his death, Sutherland attributes this to suicidal tendencies. “Virtually everything he did in life was bad for his lungs and lifespan.”

Sutherland refers to a couple of sentences in an essay, ‘How the Poor Die’ that Orwell wrote in 1942, intimating his revulsion at living beyond youth, and horror of living beyond middle age: “… it’s better to die violently and not too old … ‘Natural’ death, almost by definition, means something slow, smelly, and painful.”

At the beginning of his career, when researching The Road to Wigan Pier in 1936, Orwell had also labelled the working class as “smelly”. This obsession with smells, offensive as well as agreeable, resonated through everything he wrote. Sutherland mines all of Orwell’s published works for examples, linking them back to events and people on whom they are based.

This is literary biography at its quirkiest, revealing much of the unpleasant side of Orwell’s personality while giving him full credit for his mastery of “perfect prose”. Today that remains his legacy in an age when written and oral communication is more twisted than when the seminal Politics and the English Language was published in 1946.

Orwell’s Nose: A pathological biography, by John Sutherland (Reaktion Books).

Nevil Gibson is a former editor at large for NBR. He has contributed film and book reviews to various publications.

This is supplied content and not commissioned or paid for by NBR.