North Korea’s sinister sister lies in waiting

Kims’ dynastic double act exploits West’s kow-tow.

NBR columnist Nevil Gibson speaks with Fiona Rotherham.

Kims’ dynastic double act exploits West’s kow-tow.

NBR columnist Nevil Gibson speaks with Fiona Rotherham.

Western aid agencies depend for their survival on hungry people and the guilt of the rich world. The blame lies on capitalism and its colonialist practitioners.

Another related explanation is that too many people and too little food results from natural disasters caused by climate change, which is another outcome of capitalism and Western prosperity. Efforts by scholars to disprove these notions are swept aside if they don’t accord with political ideologies that oppose private ownership and big business.

In 2018, Alex de Waal, executive director of the World Peace Foundation and a research professor at the Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy at Tufts University in Boston, published Mass Starvation: The history and future of famine. It compiled the best available estimates of global famine deaths from 1870 to 2010 and used that data to analyse trends.

According to de Waal: “Famine is a very specific political product of the way in which societies are run, wars are fought, governments are managed. The single overwhelming element in causation – in three-quarters of the famines and three-quarters of the famine deaths – is political agency.”

It’s no surprise the three major cases of deaths from mass starvation in the 20th century occurred under socialism: three million in Stalinist Ukraine (the Holodomor) between 1932 and 1933; some 18 million Chinese in Mao Zedong’s Great Leap Forward (1958-62); and as many as 3.5 million in North Korea (1994-98) out of a then population of 22 million.

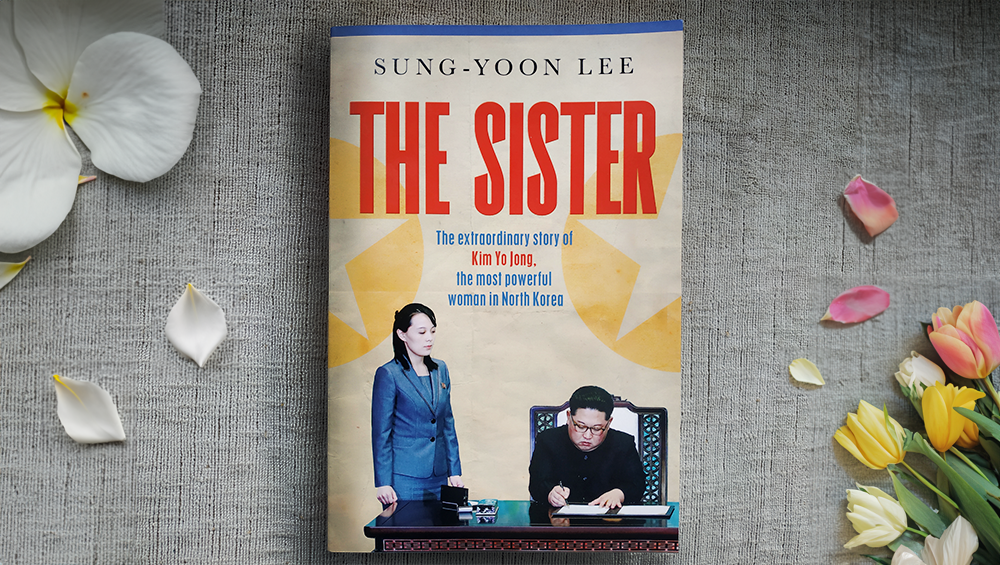

A BBC documentary last month, endorsed by Unicef, said a deadly famine had returned to North Korea due to strictly enforced Covid-related border closures that prevent food imports as well as fertilisers and farm machinery. A former teacher at the Fletcher School, Sung-Yoon Lee (Western style name),* wrote The Sister to explain how North Korea uses famine as a tool of social control and oppression, while also blackmailing the outside world.

(Note: spelling of names and use of hyphens (or not) in this review are as per the book.)

South Korean-born Sung-Yoon Lee is an academic in the US.

In the words of former dictator Kim Il Jong (Korean style name) in 1996: “[T]he food problem should be solved by socialist means. If the [Communist Workers’] Party lets the people solve the food problem themselves, then only the farmers and merchants will prosper, giving rise to egotism and collapsing the social order of a classless society.”

Kim turned food shortages and pervasive hunger into a means of fundraising, Lee asserts. “Over the next decade, hundreds of millions of dollars’ worth of free food poured in from South Korea, the US, and the UN. However, despite aid, UN agencies found approximately one-third to half of the North Korean population – about eight to 12 million – to be suffering from undernourishment.”

This remains the case today, putting North Korea among the world’s five least-nourished countries, according to a 2022 UN report (The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World). In a 2019 ranking compiled by Lee, North Korea ranked fourth after the Central African Republic, Zimbabwe, and Haiti. Yet, compared with these countries, “North Korea stands alone as an industrialised, urbanised, and completely literate society not beleaguered by insurgence and civil strife.”

Lee describes this as “deliberate starvation” that reinforces the total power wielded by a single family, the Kims, who have ruled North Korea since the end of World War II. The Sister differs from other studies of North Korea by focusing on the emergence of Kim Yo Jong, the younger sibling of Kim Jong Un, the nominal dictator and grandson of the dynasty’s founder Kim Il Sung.

Kim Yo Jong uses her platform to abuse world leaders.

Lee, who was born in Seoul, has had a distinguished academic career and is considered one of the top advisers to the US government on Korean issues. He has also travelled to North Korea and observed the Kims at close range. Although this is his first book, he has been widely published in journals and newpapers, as well as appearing at congressional hearings.

He presents Kim Yo Jong as a combination of Lady Macbeth, Madame Mao of China’s Gang of Four fame, and the Empress Dowager Cixi, who ran China in the late Qing dynasty from 1861 until her death in 1908.

Although lowly ranked in the Korean bureaucracy, as head of its propaganda and agitation arm, Kim Yo Jong’s existence was largely unknown until her first major public appearance in 2018 as the leader of North Korea’s delegation to the winter Olympics in Pyeongchang.

Lee gives detailed account of the so-called Mount Paektu Bloodline, which began with Kim Il Sung, who had two official wives. Kim Jong Il rose to become the heir apparent, taking five wives or mistresses, four of whom produced a total of seven children. In 1971, he and his father had sons, both of whom were later executed in dynastic intrigues worthy of the Ottomans or a Shakespearean drama.

One of Kim Jong Il’s partners, Ko Yong Hui, was born in Japan but was repatriated to North Korea in her teens with her family in 1962. Before her death from cancer in 2004, she had three children, Jong Un and Yo Jong, and an older brother, Jong Chol, who is best known for his interest in Elton John and plays no serious role in politics. All were educated (under pseudonyms) at an international school in Geneva, Switzerland, where coincidentally Lee first encountered their older half-brother, Kim Jong Nam, as a student in 1980.

Kim Jong Il, who died of a heart attack in 2011 aged 69 or 70. (His birth date is disputed.).

The death of Kim Jong Il in 2011 left a potential power vacuum in the Paektu Bloodline, not to mention other power players in the military and bureaucracy. But his succession plan gave the 27-year-old Jong Un enough confidence to seize the reins. Within in a year or so, five of the seven senior officials who accompanied the hearse at the funeral parade had been purged.

Lee likens Un’s grooming of his sister as akin to that of enforcer, saying: “She had already mastered the dark arts of psychological manipulation, strategic deception, fake peace overtures, hostage-taking, torture, and ad hominen name calling.”

Kim Yo Jong helps her brother Kim Jong Un sign a joint statement after a summit with South Korean President Moon Jae-in in September, 2018.

These are described in detail up to the present day. Her youthful looks and arrogant body language have fooled many foreign politicians, the most hapless being former South Korean President Moon Jae-in, whose appeasement policies were rewarded with her “foul language delivered with a sneer”. These insults have continued since the 2022 election of President Yoon Suk Yeol, who has taken a less friendly approach and been more supportive of his American ally.

In the past three years, Kim Yo Jong has stepped up her enforcement duties “as chief censor, spokeswoman, mocker, and threat-and-malice dispenser” while her enemies engage in kow-tow.

Her brother – whom President Donald Trump once labelled ‘little rocket man’ – continues to test intercontinental ballistic missiles and nuclear weapons under Chinese and Russian protection, runs major criminal drug rackets, floods the world with counterfeit US$100 bills, and wages cyberwarfare against all-comers, safe in the belief South Korea and its allies consider they have more to lose in any breakout of hostilities.

The Sister: The extraordinary story of Kim Yo Jong, the most powerful woman in North Korea, by Sung-Yoon Lee (Macmillan).

Nevil Gibson is a former editor at large for NBR. He has contributed film and book reviews to various publications.

This is supplied content and not commissioned or paid for by NBR.

Sign up to get the latest stories and insights delivered to your inbox – free, every day.