Modern-day wisdom from the Ancient World

OPINION: The Stoic philosophers developed new ways of coping with life's troubles.

OPINION: The Stoic philosophers developed new ways of coping with life's troubles.

A popular feature in the world’s oldest magazine, The Spectator, views topical issues through the lens of the philosophers of ancient Greece and Rome.

For example, last week Peter Jones used Aristotle to assess whether Vladimir Putin was a tyrant. Aristotle (384-322BC) tested four distinctions: Was he subject to law? Did he rule for a set time, or for ever? Was he elected? And did he rule over willing subjects?

Aristotle noted that tyrants suppress all views contrary to their own; destroy rival power bases, surrounding themselves with “toadies and flatterers”; and have “no public interest except what is conducive to his private ends”.

Obviously, Putin fits all these categories nicely, as does China’s Xi Jing-pin. Donald Trump does not.

While the British readers of The Spectator are likely to study classics at expensive schools and top universities, this is not the case in New Zealand, where such teaching is largely absent.

However, a small academic industry still counters the dominance of post-modernist thought. One is devoted to the Greek school of the Stoa Poikile, or painted porch, where successors to Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle debated the key philosophical issues of the day.

Unlike their contemporary philosophic schools, such as the Epicureans and Cynics, the Stoics retain their original dictionary meaning. Stoicism is commonly used to describe Ukrainians, who are under constant Russian rocket attacks. The same goes for the multitude of frontline workers coping with the Covid-19 pandemic.

The Oxford Companion to Philosophy provides this definition: “Stoicism placed ethics in the context of an understanding of the world as a whole, with reason being paramount in both human behaviour and in the divinely ordered cosmos.”

Ethical foundation

This ethical foundation has survived philosophic discussion down the centuries, being absorbed into Christianity and still alive today in quotes by politicians, priests, and others in public life.

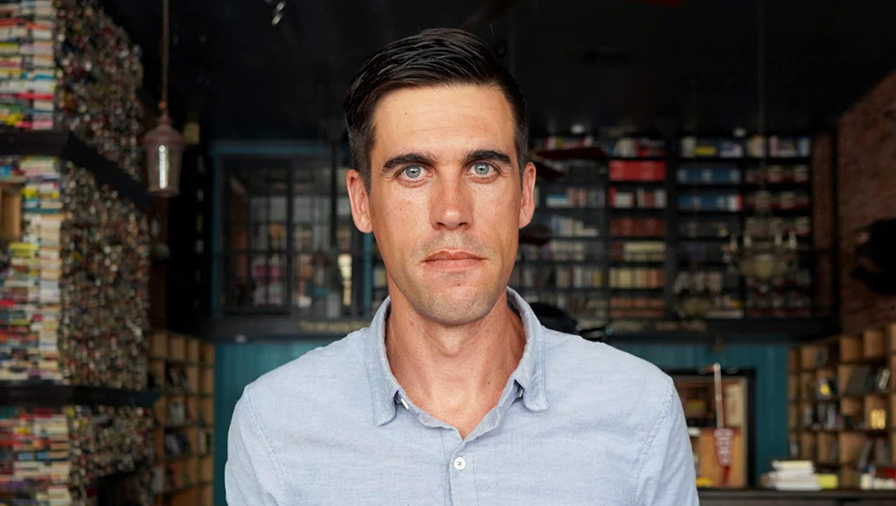

Ryan Holiday, a Texan author and owner of a bookshop, The Painted Porch, has devoted his career to promoting Stoicism as a way of life for anyone who wants to make the world a better place, or just be fulfilled as an individual.

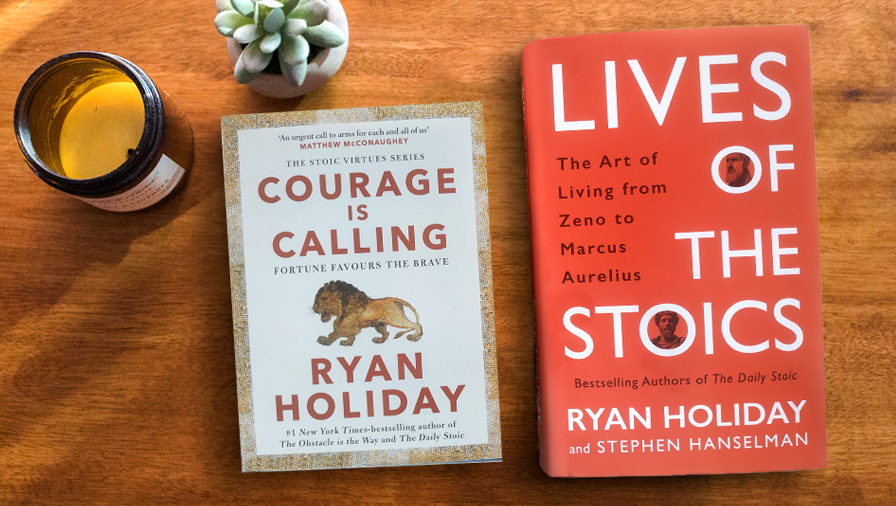

He has written eight self-improvement books, the latest of which is Courage is Calling, a collection of 65 short chapters illustrating examples of this Stoic virtue in acts of heroism and how to overcome fear. With co-author Stephen Hanselman, Holiday produced The Daily Stoic: 366 Meditations on Wisdom, Perseverance, and the Art of Living (2017). It includes new translations of works by Stoic writers such as Seneca, Epictetus, and Marcus Aurelius. The eponymous website claims 300,000 subscribers to its daily email meditation.

Their latest book, Lives of the Stoics, moves away from the devotional mode to historical, with 26 profiles, from the school’s founder, Zeno (334-262BC), to its most powerful practitioner, Roman Emperor Marcus Aurelius, who died in 180AD.

Zeno was eight when Aristotle died in 322BC, and from Crates the Cynic reputedly learned the virtues of continence and self-mastery. Zeno’s arrival in Athens was due to a shipwreck that ruined his family’s merchant fortune, to which he responded by adopting a life of resilience and self-discipline, as well as being indifferent (apatheia) to misfortune and suffering.

Holiday and Hanselman describe Zeno as Stoicism’s prophet, choosing Judaic/Christian biblical terms, with Cleanthes as the apostle. Zeno came from today’s Cyprus and Cleanthes from Asia Minor (Turkey). They both gravitated to Athens, which had a population of 25,000 citizens and hundreds of thousands of slaves.

The Stoics thrived with their rules for practical living against the other schools, which favoured more abstract thinking. Stoicism could be applied to commerce and politics as well as private morality among the well-heeled.

Rise of Rome

Roman power was beginning to eclipse the Greek states, imposing a huge financial penalty on Athens in a dispute against one of its neighbours. This was reduced thanks to the fifth leader of the Stoa, Diogenes (230-142BC), whose diplomacy and networking was persuasive.

Diogenes, originally from Babylon and not to be confused with Diogenes the Cynic, articulated rules for a market economy, with concepts such as caveat emptor and pointing out the impossibility of full disclosure in transactions.

“The seller should declare any defects in his wares … but the rest, since he has goods to sell, he may try to sell to the best possible advantage, provided he is guilty of no misrepresentation,” as chronicler Cicero later put it.

After its birth in democratic Greece, Stoicism matured into a pragmatic guide for citizens of the Roman republic. For example, Panaetius (185-109BC), born in Rhodes, was widely travelled and soon became influential among Rome’s elite.

Holiday and Hanselman describe Panaetius as a “weaver,” who tied together Stoic and Roman ethical perspectives, while also ensuring its provinces were treated with respect. He did this through missions to Egypt, Cyprus, Syria, parts of Greece, and Asia Minor.

This globalist outlook was later reflected in Marcus Aurelius describing himself as a “citizen of the world” and the lack of provincial thinking among the Stoics. For modern-day progressives, Stoicism is also relatively free of gender, racial and sexual biases, while putting an emphasis on individual agency.

Political intrigue

Cicero (106-43BC) was influential in spreading Stoic ideas, though not fully embracing them himself. He returned to Rome aged 29 after a decade’s study, becoming heavily involved in political intrigue that eventually led to the death of Julius Caesar and the republic turning into one-man rule.

Cato, Rome’s ‘Iron Man’, was counted among the Stoics, as was his daughter, Porcia (Portia in Shakespeare’s account), the only woman profiled in the book. She later married Brutus, who told her of the plot to kill Caesar after she displayed her Stoic resistance to pain with a self-inflicted wound.

The Stoic most remembered today, apart from Marcus Aurelius, is Seneca (4BC-65AD), a Spaniard who survived through the earliest five emperors when the Roman empire had a population of 45 million. After one period in exile, which occurred frequently among the Stoics, he was recalled by Agrippina to tutor her son, Nero.

She killed Claudius, elevating Nero to emperor at 16. Nero proved a poor pupil, murdering his mother, half-brother Britannicus, and anyone else who stood in his way. Seneca eventually escaped Nero’s grasp after the Great Fire of 64AD destroyed Rome, hoping to spend the rest of his life writing and in contemplation. But Nero caught up with him, forcing his suicide, a fate shared by many of the Stoics.

But if their lives were cut short, their ideas survived until the reign of Marcus Aurelius (121-180AD), the philosopher king who most reflected the four Stoic virtues first articulated by Zeno: courage, temperance, justice, and wisdom.

Marcus Aurelius was the grandson of Hadrian, who had engaged as a tutor the most prominent of the late Stoic philosophers, Epictetus, a former slave, soldier, and general. None of his writings survived but a student later published eight volumes of his lectures.

Marcus Aurelius ruled Rome during the 15-year Antonine Plague that killed five million, and border wars that lasted 19 years. The loss of eight of his 13 children before they reached adulthood weighed heavily on his best-known work, Meditations, which was published in 167AD and remains key Stoic text.

Cicero summarised Stoicism’s ethical outlook as “to learn to philosophise is to learn how to die”. Or, as explained in AC Grayling’s The History of Philosophy (2019): “If you are not afraid of death you are ultimately and completely free, because you always have an escape from the intolerable. Freedom from the oppression of anxiety and fear, and from desiring what one cannot oneself achieve or gain, is happiness itself.”

That is bound to keep Stoicism relevant in troubling times.

Courage is Calling, by Ryan Holiday (Profile Books) and Lives of the Stoics, by Ryan Holiday and Stephen Hanselman (Profile Books).

Nevil Gibson is a former editor at large for NBR. He has contributed film and book reviews to various publications.

This is supplied content and not paid for by NBR.

Sign up to get the latest stories and insights delivered to your inbox – free, every day.