Maurice Shadbolt: A man of his time

OPINION: The life, works and loves of New Zealand’s first full-time professional writer.

OPINION: The life, works and loves of New Zealand’s first full-time professional writer.

The cure for child poverty may be more money but it will take more than cash to reverse falling literacy rates. In the past week, a Ministry of Education action plan has been rejected by a wide range of critics, including teachers. They range from the Education Hub think tank, Māori academic Melissa Derby, and former teacher Caleb Anderson to charter school founder Alwyn Poole, Richard Prebble, and Alan Duff.

All, to one degree or other, partly blame the ministry itself for this alarming drop by international standards. The ministry is accused of opposing tested teaching methods; rejecting Western notions of science, mathematics, and literacy; and not putting an emphasis on reading.

Education Hub’s latest report shows reading levels since 2009 have fallen faster than in comparable countries, and the proportion of students at the highest levels has also declined. At year eight, 44% of pupils perform below the curriculum level.

Derby rejects literacy as a solely Western competency and that Māori striving for excellence in reading and writing is not a modern-day act of colonialism. Literacy is the best way for individuals to improve their future prospects.

Poole, in a series of open letters to the Secretary for Education, questions the ministry’s competency to narrow the gap between the top 10 secondary schools and the lowest 42, ensuring easy pickings at the bottom of society for criminal gangs and a lifetime of low-paid work.

The latest National Reading Survey by Horizon Research shows the number of adults who read or started at least one book fell from 86% to 85% in the past 12 months. For 10 to 17-year-olds, it was 94%, down from 97% in 2017. Reading habits was worse among men, with 79% picking up a book in the past year, compared with 81% in 2018 and 84% in 2017. Women’s reading habits have remained steady since 2018.

Publisher’s plea

Allen & Unwin’s New Zealand publisher, Michelle Hurley, says sales of New Zealand fiction are “dismal” compared with the Australian market, where the company is based.

Just two fiction titles featured in the top selling New Zealand titles in 2021: Auē (first published in 2019) and To Italy With Love. As a result, Allen & Unwin is offering a $10,000 advance to a prospective novelist.

The country’s top literary award, the Jann Medlicott Acorn Prize for Fiction, is worth $60,000 and will be announced on May 11. Three of the four shortlisted authors are women, reflecting the market’s strong feminine skew.

Hurley is aiming to attract writers of commercial, as opposed to literary, fiction – “well-written, propulsive, character-driven novels” in all genres.

“The kind of book that if you have to put it down, all you want to do is pick it back up, and that when you finish, you’ll tell your friends about it.”

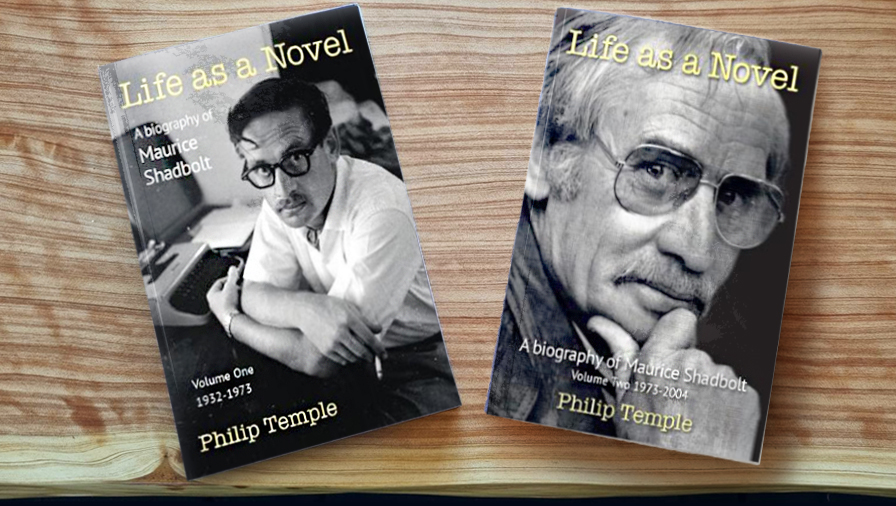

This is not a pipe dream. New Zealand has been here before, and the evidence lies in the second volume of Philip Temple’s Life as a Novel, a biography of Maurice Shadbolt.

Shadbolt always wanted to earn a living as a writer, an ambition that eluded most others who did it as a sideline to teaching or other job. His talent first emerged in the 1950s, when in his 20s he was selected with four others, Gordon Dryden, Hone Tūwhare, Conrad Bollinger, and Noel Hilliard, in a Young People’s Club competition to attend a Communist Party-inspired Carnival for Peace and Friendship in Sydney.

University dropout

Shadbolt dropped out of university, travelled to Eastern Bloc countries and, at 27 in London, had a collection of short stories, The New Zealanders, accepted by Victor Gollancz Ltd, the publisher with distinctive yellow jackets. He was in good company; other New Zealanders being published in London included Ian Cross (The God Boy), Janet Frame (Owls Do Cry), and Sylvia Ashton-Warner (Spinster).

Back home from his first OE, Shadbolt became, in Temple’s words, New Zealand’s first full-time professional author. A local edition of The New Zealanders was successful and popular Kiwi fiction was on a high, with Barry Crump’s A Good Keen Man and Hang on a Minute Mate selling 100,000 copies.

After a Burns fellowship in Dunedin, and establishing himself back in Auckland, Shadbolt embarked on novels that drew heavily on his background in a peripatetic Irish farmer-settler family that lived in 40 houses in both rural and urban settings.

Among the Cinders, his debut novel, had a teenage boy at its centre while the expansive Strangers and Journeys (1972) was published in Shadbolt’s 40th year. He was the country’s most travelled writer, turning out Shell Guides, lucrative assignments for Reader’s Digest and National Geographic, and the bestselling coffee table book, Gift of the Sea, with photographer Brian Brake.

Shadbolt’s fiction started to incorporate topical issues, such as nuclear testing in French Polynesia and Hokianga’s dolphin Opo, while a commission in 1975 from the NZ Listener on the Bill Sutch espionage case ran to 12 pages, a pioneering example of long-form journalism.

In 1979, the Reader’s Digest published a lengthy piece on Arthur Alan Thomas that was instrumental in Prime Minister Robert Muldoon granting a pardon six weeks later, while the Air New Zealand crash on Mt Erebus was the subject of another.

Reputation enhanced

Shadbolt’s reputation was further enhanced by his pioneer epic The Lovelock Version, completed during one of his regular stints in London, where all of his books were prominently reviewed. He was praised for his storytelling and style, with favourable comparisons with American realists such as John Steinbeck, Ernest Hemingway, Nathaniel West, and Thomas Wolfe, as well as contemporaries John Updike, Norman Mailer, John Barth, EL Doctorow, and the South American Gabriel García Márquez.

Academic recognition was less effusive, as Shadbolt was seen as too commercial for serious literary study, though one likened his novels to the classic works of Walter Scott. Research for the chapter on Gallipoli in The Lovelock Version led to a TV series in the early 1980s. Before becoming a full-time writer, Shadbolt had worked on newsreel documentaries, though the medium did him little justice (the only features to be completed was a German adaptation of Among the Cinders and a version of the play Once on Chunuk Bair).

Gallipoli: The New Zealand story was controversial, as Shadbolt felt his script was toned down because of the involvement of Sir Leonard Thornton as presenter. Shadbolt had access to diaries, letters, and interviews of many veterans, and wanted their views reflected rather than the military’s top brass.

Once on Chunuk Bair revived the debate over the death of Wellington war hero William Malone by British ‘friendly fire’, which Shadbolt had learned from collaborator and military historian Christopher Pugsley. In a review, Mervyn Thompson described the play as “the birth of a nation”. It changed the mythology surrounding Anzac Day. The ructions continued when Shadbolt published the veterans’ interviews and other sources that were dropped from the TV production.

Meanwhile, he was deeply immersed in his New Zealand Wars trilogy, with fictionalised versions of three central figures, Te Kooti (Season of the Jew), American adventurer Kimball Bent (Monday’s Warriors), and Hōne Heke (House of Strife). All presented a strong and positive view of Māori resistance.

With reprints and revisions of earlier works, international versions, and sales of movie rights, Shadbolt in the early 1990s became one of the country’s top 5% of earners and was at the “peak of success”. The first of two memoirs, One of Ben’s, immediately sold 11,000 copies on publication in 1992.

Turning point

This emphasis on the colonial past gave New Zealanders a new understanding of how their nation was forged by two races. It was also a turning point in Shadbolt’s own thinking, as he pushed back on a more radical interpretation that demanded separate racial sovereignty and denigrated the contribution of European settlers.

“This is a new fundamentalism as fervent as the Christian and Moslem kind,” he wrote, rejecting the word ‘pākehā’ as no longer useful in a multicultural country that was part of a globalised world.

Shadbolt never flinched from an argument on this or other issues, some of which remain relevant today. Temple’s highly detailed account tracks Shadbolt’s involvement in various literary disputes, as well as public protests against the Vietnam war and the Springbok rugby tour. But it’s his private life that will draw readers interested in more salacious stuff.

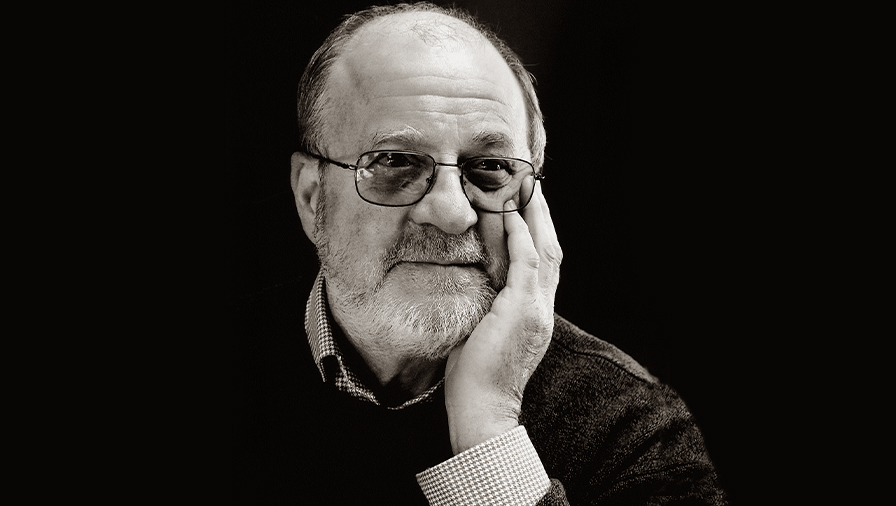

Temple makes full use of Shadbolt’s private journals as well as interviews with many of those who knew and lived with him. Biographies of literary figures rarely overlook their frailties and vices.

Early on, Temple describes Shadbolt as a man of his time: “The writer as creative hero, entitled to women and drugs, drifting into sexual and alcoholic addictions and violence.” The parallels with others before him are tempting – Charles Dickens, Karl Marx, and HG Wells come to mind, as do Hemingway, Mailer, Jack Kerouac, William Burroughs and, more recently, Philip Roth.

Shadbolt had four wives – Gill (nee Heming), Barbara Magner, Bridget Armstrong, and Elspeth Sandys, all prominent in their own fields – and many affairs, including with opera star Beverley Bergen, artist Andrea Stevens (Robinson), and sisters Marilyn Duckworth and Fleur Adcock.

These relationships, parenting five children, and a workaholic lifestyle put a heavy toll on Shadbolt’s physical and mental health. In 1997, like his mother Violet, he was diagnosed with dementia, and he died at a rest home in Taumarunui in 2004, aged 72.

Temple’s task has taken nine years and he adds to an impressive collection of recent books about New Zealand writers. They form a sound foundation for any course that enhances literacy skills, not to mention potential movies. Moves are also under way to restore Shadbolt’s residence in Titirangi, Auckland, which he bought in 1964, as a writer’s retreat to match Colin McCahon’s nearby one for artists.

Life as a Novel, A biography of Maurice Shadbolt. Volume One, 1932-1973. Volume Two, 1973-2004, by Philip Temple (David Ling Publishing).