Looking back, looking forward: My year in books 2024

ANALYSIS: NBR's reviewer recaps his favourites from a year’s reading and anticipates ones to come.

Nevil Gibson ponders the heavy weight of having to read, read, read...

ANALYSIS: NBR's reviewer recaps his favourites from a year’s reading and anticipates ones to come.

Nevil Gibson ponders the heavy weight of having to read, read, read...

If there’s a common theme running through the past year’s reading, it’s that lessons from the past are best digested through the leisure of slow thinking.

The pressure of absorbing large amounts of information in the shortest available time must be the major curse of modern living. It has created a generation addicted to TikTok videos and a decline in what is disparagingly called ‘legacy’ media.

But getting the best out of the latest technology still depends on literacy and the ability to communicate effectively. Book writers and publishers have not yet succumbed to an apocalyptic fate.

Would Boris Johnson have attracted an audience prepared to pay $495 to hear him in person if he didn’t have a book to promote? That it runs to nearly 800 pages – which Amazon.com calculates as 15.25 hours’ reading – is testament to the pulling power of a book, no matter how it is presented.

For my part, I have put Unleashed aside for summer reading along with several others, mentioned further down this column.

Getting the best out of the latest technology still depends on literacy and the ability to communicate effectively.

Ian F Grant.

The bulk of my reading in 2024 was dedicated to New Zealand non-fiction titles and a sprinkling of historical fiction sent to me by the authors, some of whom self-published. As middle-aged men, they found it hard to resist the juggernaut of female book editors and buyers. If men have become non-readers of fiction, they have only themselves to blame.

But male writers held their own in non-fiction. Ryan Bodman’s social history of rugby league was judged winner at the Ockham Book Awards. Its class-based, socio-economic approach stood it apart from run-of-the-mill sports books and suggests other codes, affinity groups, and leisure pursuits could do with a similar historical analysis.

The more-the-better formula also featured in Ian F Grant’s second volume of his newspaper history, Pressing On, which covers the years 1921 to 2000. If you’ve ever worked on a paper, you will find it mentioned here along with many stories ranging from corporate manoeuvrings, to closures and launches.

The economy came under scrutiny in two widely differing accounts: New Zealand Herald business editor at large Liam Dann’s popularised primer BBQ Economics, and Brian Easton’s In Open Seas. The latter brings his historical analysis of the economy up to the 2017-23 period under a Labour Government. Originally a self-published e-book, Easton informs me it is now available in a hard copy version.

The wider business scene produced one surprise and NBR exclusive, Digi-Tech founder John Reid’s exposé of his fraud trial back in 2004 as well as two insider accounts of the Environmental Defence Society and the living wage movement. Reid’s A Few Bad Men is controversial, to say the least, and names those he considers guilty of a cover up and corruption. Strangely, they have failed to respond to his damaging accusations.

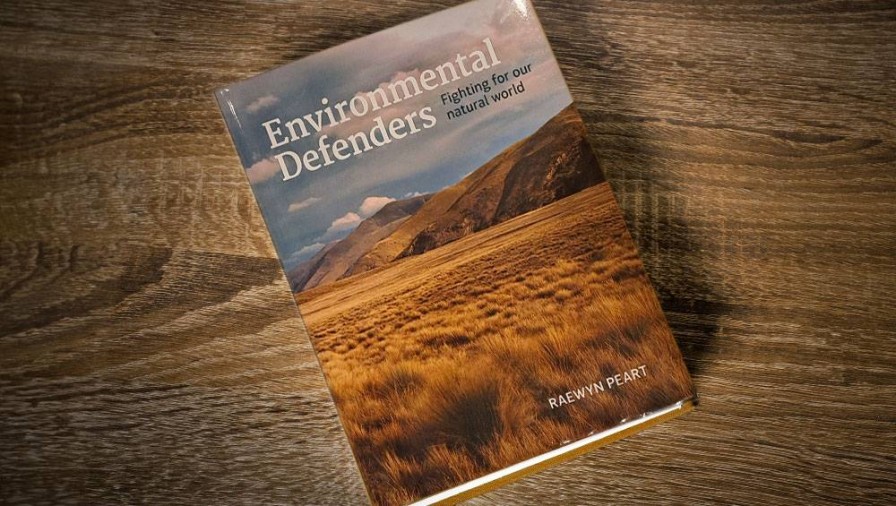

By contrast, Raewyn Peart’s Environmental Defenders and Lyndy McIntyre’s Power to Win were less impassioned in their balance and research for their respective causes.

On the political front, the only memoir of note, Derek Quigley’s Challenging the Status Quo, showed the benefits of hindsight. He emailed me from Madrid, where he lives in retirement, to rebut my comment about his lack of radical zeal by attaching a recent paper on defence issues in the Pacific and alerting me to a forthcoming one on family violence. His approach to both topics is to promote practical outcomes rather than the theoretical, which was a hallmark of his politics.

Professional men writing historical novels in their near retirement may be unpopular with publishers. But this didn’t stop three of them impressing me this year.

Auckland lawyer Dermot Ross chose Ernest Hemingway as his muse for Hemingway’s Goblet, a reimagining of the writer’s summer in Spain in 1925 through the eyes of a contemporary and his modern-day descendant.

Dunedin accountant Christopher Worth continued his World War II trilogy The Rabbit Hunter with his fictional hero embroiled in the Battle for Crete, while Manukau District Court judge Alan Goodwin delved into the adolescence of Britain’s most famous scientist, Sir Isaac Newton, for Greene Lyon.

Big ideas and big concepts dominated the book world outside New Zealand. The most compelling business book was Gary Stevenson’s The Trading Game, a true morality tale about the rise and fall of a financial trader, a self-styled street-smart guy with a photographic memory and gift for mathematics.

Hannah Ritchie.

The history of information network up to the age of artificial intelligence was the subject of Nexus, by Yuval Noah Harari, an Israeli polymath and one of the founders of the bestselling big-idea genre. Not the End of the World, by English data scientist Hannah Ritchie, provided a welcome fact-based antidote to climate change alarmism, and showed it was possible to achieve sustainability without sacrificing living standards.

Anne Applebaum’s Autocracy, Inc: The Dictators Who Want to Run the World outlined an authoritarian network that poses far more danger to the Western democracies than the free-market Atlas conspiracy.

For another publication, I reviewed William Dalrymple’s The Golden Road: How Ancient India Transformed the World. He describes how, through trade, missionaries, and sometimes conflict, India’s soft power expanded into Central and Southeast Asia for a millennium and a half from about 250BC up to the arrival of the British Raj. Dalrymple’s anti-colonial views make him reluctant to give credit to the scholars who uncovered and preserved the artifacts of ancient India’s Buddhist culture and its invention of mathematics.

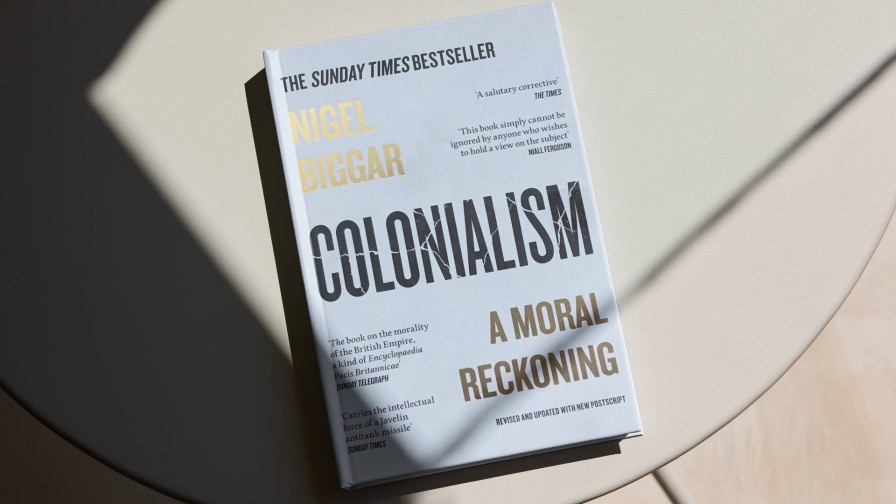

Leading the pushback for a more balanced assessment of the British Empire is English clergyman and ethicist Nigel Biggar, whose Colonialism: A Moral Reckoning also examines the high human cost of regimes that resulted from decolonisation in the late 20th century.

Apart from Johnson’s behemoth autobiography, I have lined up some heavyweight reading for columns in the new year. I will finish off Josephine Quinn’s 500-plus-page How the World Made the West, covering 4000 years of human history.

For would-be and practising executives, Steve Vamos’s Through Shifts and Shocks lists lessons learned from working at Xero, Microsoft, and Apple. Wellington KC Daniel Kalderimis has personal insights in Zest: Climbing from Depression to Philosophy on how to have a more fruitful life.

I will also check out, at the suggestion of a former Victoria University colleague, Ian O Williamson’s edited collection of academic essays on the workplace. It is part of the ‘Critical Conversations’ series published by the Johns Hopkins University Press. Williamson was Pro Vice-Chancellor and dean of Victoria’s school of business and government. He is now dean of the Paul Merage School of Business at the University of California, Irvine.