Looking back from a film festival fiasco

OPINION; Why a 50-year-old cultural institution faces an uncertain future.

OPINION; Why a 50-year-old cultural institution faces an uncertain future.

In 2019, the New Zealand International Film Festival attracted a quarter of a million attendances to its 155 features from 47 countries at 13 centres around the country.

Today, that festival’s future is in doubt, after a near million-dollar loss in 2021. Covid-19 is being blamed but I believe that’s only part of the explanation.

In 2020, as the global lockdown hit cinemas and film production, the NZIFF pioneered a hybrid mix of online presentation and selected screenings at 15 cinemas that were still open. The number of features fell to 79.

It was a model successfully copied by other festivals. Last year, for example, the French-language Cinemania in Montréal, Canada, had 77,000 viewers compared with 30,000 in pre-pandemic times. It sold 1500 passports compared with the previous year’s 500. This greatly increased attendance was due to making the films available to all Canadians, with English subtitles.

This year, Cinemania upped the hybrid model to 100 online and 128 theatrical screenings of 85 features over 13 days. This compared with just 63 theatrical screenings in 2018.

By contrast, the NZIFF gambled this year in postponing the traditional mid-July start of the festival to October and ditching the hybrid model in favour of theatres only. The decision proved disastrous. A three-month lockdown forced a complete cancellation in Auckland and Hamilton, while attendances in Wellington, Christchurch, Dunedin, and eight other centres failed to cushion the financial blow.

Poor attendances

The poor attendances cannot have been due to the lack of a quality offering. The Christchurch programme ran to 100 features, including several dozen must-see award winners that are the core of any festival.

What had changed was the direction and marketing of the festival from a path it had followed for some 50 years, since the first Auckland International Film Festival staged in 1969 (and which I attended). That was followed soon after by Wellington, eventually morphing into the New Zealand International Film Festival, as it was known until recently.

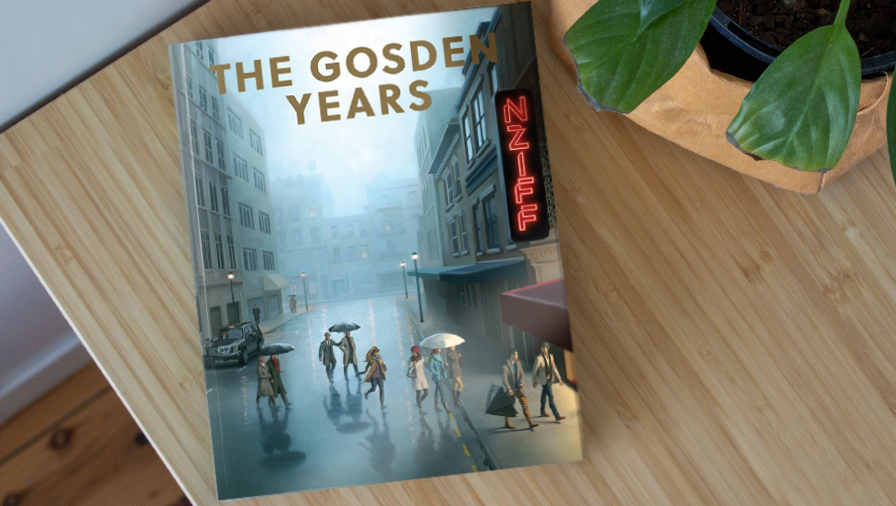

The history of these festivals, and their origins in earlier attempts, is told in The Gosden Years, a $50 glossy, coffee table book edited by Dame Gaylene Preston and Tim Wong. It is compiled from the writings of Bill Gosden, who died in 2020.

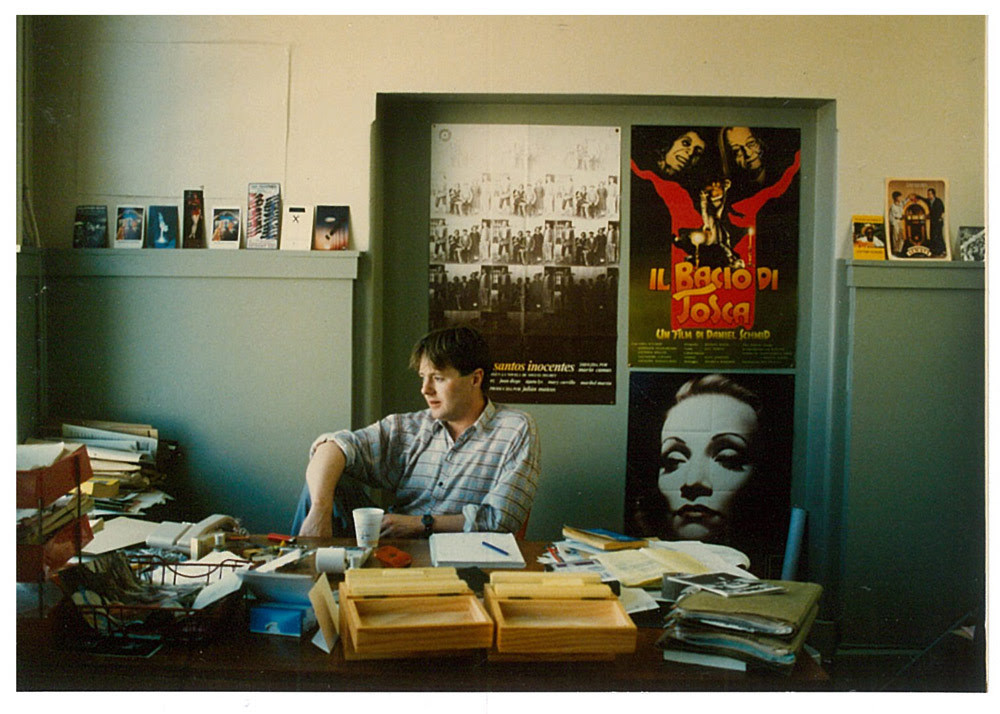

He started work at the NZ Federation of Film Societies in 1979. Two years later, he replaced Lindsay Shelton as director of the Wellington International Film Festival, then in its 11th year.

Its most celebrated attraction was Ermanno Olmi’s The Tree of Wooden Clogs.

Original impulse

It was the kind of film that prompted Gosden to write: “The impulse that brought the first Wellington and Auckland festivals to life was the desire to see movies that weren’t making it to New Zealand.”

Later, introducing the 1998 programme, he wrote of a “magnificent selection of films about blood sports, bad fathers, sexual masochism, addiction, racist politics, sexism and cruelty in the workplace, murderous homophobes, prisoners on death row, children who murder, brain-damaged accident victims, to be or not to be, the Holocaust and, to cap it all, a documentary about the ageing process.”

Festival fans will acknowledge not much has changed in the content of the world’s best films, and nor should it. But compare Gosden’s targeting with that of his successor, whose intentions were described as follows in one newspaper interview: “High on his wish list is reaching audiences who aren’t usually represented among the urban middle class, and slightly older fans.”

Therein lies the explanation, I believe, of why the festival has become a cultural victim, in economic terms, of the class war against the middle class. It has happened in other arts, such as opera, and in attempts to abolish concert radio, where the core purpose and audiences are ignored in favour of an agenda to undermine long-standing values. The success of writers’ festivals, also Covid-affected, is that they target a known and reliable market without hidden agendas.

Many battles

Gosden and his colleagues understood this, and fought many battles in an industry where commerce, art, and community standards clash at many levels. Not the least of these is government intervention through censorship and a revenue grab that imposes costs on all movie screenings.

In the early 1990s, Gosden was publicly attacked by the censor for “objectifying women” and as a result she banned Henry; Portrait of a Serial Killer. It was the beginning, Gosden writes, of a cultural war about “cancelling” films that “demean” people.

In 2002, the Society for the Promotion of Community Standards tried stop the opening night screening of a Mexican film, Y tu mama también, through an injunction that was overthrown only hours before start time. Today that film, directed by Oscar winner Alfonso Cuaron, wouldn’t cause a blink compared with what’s available on TV or Netflix.

Meanwhile, the theatrical side had undergone dramatic changes from a regulated two-chain system tied to particular distributors into an open market that could compete with home viewing of video cassettes and DVDs.

The quality of cinemas improved, after Hollywood-controlled distributors said they would favour investment in multiplexes, and entrepreneurs such as Barrie Everard spotted opportunities in full-time arthouse cinemas.

Upgraded theatres

Gosden supported these moves, leading to the upgrades of the Embassy in Wellington, where Sir Peter Jackson staged a Lord of the Rings world premiere, and the Civic in Auckland.

After the millennium, the industry went through more dramatic changes with the switch to digital production and projection. Cans and spooling of film were replaced by digital devices, vastly reducing costs and enhancing accessibility.

Filmgoers could access overseas reviews online to see what was available, and video stores were booming. The festivals responded by greatly increasing their selection. The 2006 programme, for example, ran to 228 pages in A5 format, compared with 2019’s 100 pages in A4. If anything, the festivals became bloated by adding many extras such as animation, Ant Timpson’s Incredibly Strange, and the promotion of shorts.

While the initial Wellington festival in 1972 offered just nine films, opening with Eric Rohmer’s Claire’s Knee, no-one could possibly see more than a proportion of the 160 features screened in 2013 or the 177 in 2018.

Not all foreign

Although the festivals were primarily about foreign films, and seeing the best of the world’s other cultures, Gosden gave generous access to the local industry, even if it wasn’t fully justifiable on commercial grounds.

The festivals, before 2020, were self-supporting at up to 95%, with a top-up from government agencies to promote the output from the heavily subsidised production sector.

In particular, Gosden tracks the festivals’ support for Preston, from her Mr Wrong in 1985 through to My Year With Helen in 2017, as well as for Jane Campion, from Sweetie and Angel at My Table in 1990 to this year’s The Power of the Dog, which, while filmed here, is set in Montana.

But Gosden’s lesson is that the focus of an international festival should be on the key audience proposition to see the best of the world’s cinema, not a prop for local producers.

Of course, some meet both criteria, as Campion and others showed with The Dark Horse, The Rehearsal, and Poi E. So did Jackson’s Heavenly Creatures back in 1994.

The uncertain future

The future of an international film festival for New Zealanders, as opposed to one promoting cultural change to fulfil desired outcomes, remains to be seen. It will need a huge injection of funds. The worst outcome would be a government bailout with strings attached. Overseas distributors won’t be impressed by the lack of commercial nous shown by Gosden’s successor, who has since resigned and returned to the Netherlands.

As for frozen-out Auckland festival fans, there is some compensation in Timpson’s ‘In the Shade’ festival over a fortnight in late January at two independent but less than perfect cinemas. He has selected a whopping 35 foreign features from the Christchurch NZIFF programme and added another 17. That leaves 27 foreign features, by my count, that may or may not surface again now that all cinemas are open.

Festival buffs should note that no less than 20 titles from both lists are in Sight & Sound’s top 50 of 2021 chosen by 100 world critics. If Timpson and his colleagues succeed, he would be an appropriate person to carry on Gosden’s legacy.

The Gosden Years: A New Zealand film festival legacy, by Bill Gosden. Edited by Gaylene Preston and Tim Wong (VUP).

Nevil Gibson is a former editor at large for NBR. He has contributed film and book reviews to various publications.

This is supplied content and not paid for by NBR.

Sign up to get the latest stories and insights delivered to your inbox – free, every day.