Learning from Lawrence in lockdown

A feminist critic rises to the challenge of a dead white male.

NBR columnist Nevil Gibson speaks with Fiona Rotherham.

A feminist critic rises to the challenge of a dead white male.

NBR columnist Nevil Gibson speaks with Fiona Rotherham.

I’m told by university lecturers that few of their students turn up for their classes any more. Instead, they stay at home and watch them online at their leisure.

Traditionalists will lament the loss of face-to-face learning and wonder whether it means a decline in the quality of degrees.

Of course, high education institutions throughout the world have long been delivering lectures online, giving wide access to some of the world’s best brains. But deserted lecture theatres also mean fewer students spending their days on campus, indulging in intellectual and other pursuits.

While the lack of debating ideas and socialisation may be a loss, solitary activities such as reading have not lost their relevance. Writer, literary critic, and cultural historian Lara Feigel has no doubts about the importance of books in her life.

Professor Lara Feigel.

“When I picture a world without books – when I worry, for example, that my son doesn’t read – I picture a world with less openness to the otherness of other minds,” she says.

Feigel, who is professor of modern literature at King’s College London, goes on to say: “… what books have given me is not just a capacity for empathy but something madder and more destructive: a willingness to dwell with my own capacity for negative feeling, for doubt, sadness and anger.”

They have given her the ability to accept failure, whether it be in her career, marriage, or having children, and “shown a way to integrate the madness and destruction into a liveable life”.

I cannot imagine anyone, particularly a student of literature, who wouldn’t want to attend a lecture by Feigel, who has written books on literature, cinema, and politics, 1930-45; a study of Doris Lessing (Free Woman, 2018); the lives of writers in wartime London (The Love-Charm of Bombs, 2013) and post-war Germany (The Bitter Taste of Victory, 2016); and a novel, The Group (2020), which updates Mary McCarthy’s 1963 classic.

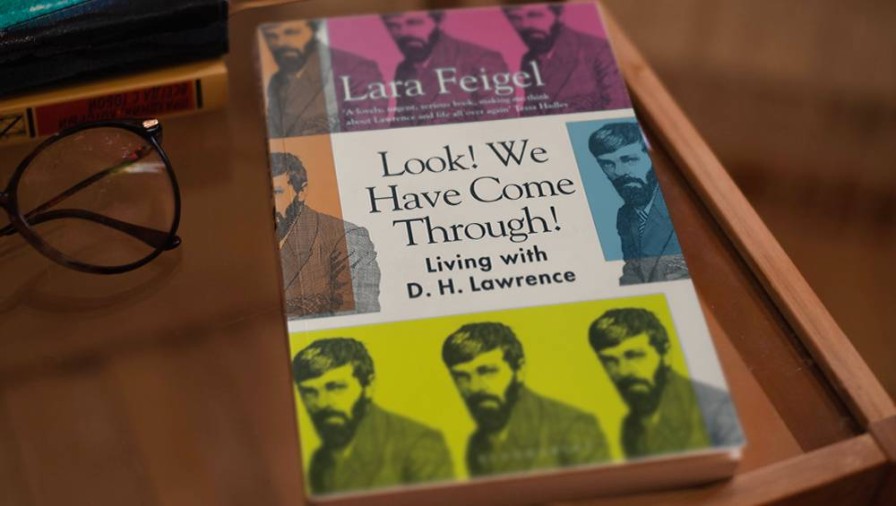

Feigel’s latest mix of literary criticism, biography and personal memoir is Look! We Have Come Through! It’s about early 20th century novelist DH Lawrence. The title is taken from one of his early book of poems.

For someone whose reading at university in the 1960s was heavily into Lawrence and the more contemporary Lessing, Feigel is hard to resist. Both were considered radical in their day but today do not fit easily within academia’s post-modernist framework. They may even be unknown or forgotten.

Feigel confesses she was underwhelmed by Lawrence when she was an undergraduate at Oxford in the 1990s. But a marriage separation, two young children, a new partner, and enforced seclusion in the English countryside during the lockdowns of 2020 and 2021 enabled her to tackle a long-overdue project.

Lawrence’s reputation after his death in 1930 had been cemented by critics such as FR Leavis as one of Britain’s greatest writers. In just 20 years, Lawrence produced 11 novels, nine volumes of short stories, 900 pages of poetry, and eight plays.

His profile received another boost in 1960 when his final novel, Lady Chatterley’s Lover, written in 1927, was published in its unexpurgated version after an obscenity trial. Film and TV adaptations peaked in the 1980s, exploiting Lawrence’s notoriety rather than his literary achievement.

As male dominance of academic literary scholarship declined in the 1970s, feminist critics such as Kate Millett ridiculed Lawrence as a misogynist and pornographer.

When she turned 30 in 2012, Feigel started to doubt the feminist critique she had absorbed at university, finding much to admire in Lawrence’s female characters, particularly those in The Rainbow and Women in Love. She is not alone; some female writers have used Lawrence as inspiration for characters in their own novels.

DH Lawrence and Frieda Weekley in Mexico 1923.

The biggest influence in Lawrence’s life was his German-born lover and later wife, Frieda Weekley (née von Richthofen), whom he first met in 1912 when he was a struggling writer of 27 and she was a married woman of 33 with three children. Like Lessing, Frieda abandoned her family to become a ‘free woman’. She travelled with Lawrence to Germany and Italy, where he finished the final version of Sons and Lovers, published in 1913.

Feigel explores their lives and copious writings through eight chapters, each reflecting different intellectual and physical aspects. These start with Lawrence’s response to Frieda’s knowledge of Freud, that the unconscious resides in the body rather than the mind; and that wilfulness – the desire to have power over others – is wrong, even though he urges people to fight back.

These chapters reveal Lawrence as a “self-taught intellectual who wanted to engage with the largest minds of his day but was also disposed to be contemptuous and truculent”. Feigel wonders about her own ‘wilfulness’ as she manages two young lives in the lockdown.

Chapters on sex, parenthood, and communal living reveal ideas on not over-identifying with children and animals, because there are other feelings that allow for freer relationships. These “open us to the constantly shape-shifting nature of desire and the mutability that sets up in our relationships”.

Lawrence rejected the domesticated marriage his parents and grandparents had. The couple in The Rainbow submit themselves to a relationship of conflict and flux, Feigel states. “They want a new kind of coupledom [with] a modernity that has yet to be born.”

Contrary to myth, Lawrence was opposed to the eroticism of pornography, hated promiscuity, was homophobic despite his fascination with it, and despised body parts. He wasn’t sympathetic to Frieda’s attempts to gain access to her children, a quest in which she was supported by Katherine Mansfield.

Mansfield and John Middleton Murray were close friends with the Lawrences, and even joined them in Cornwall for a brief experiment in communal living. That was in 1916 but Lawrence’s temper drove them back to France. The ‘community’ of two couples is the basis for Women in Love, which was turned down by four publishers in 1917 but, like The Rainbow before it, survived attempts to suppress it.

After being harassed and forced to leave Cornwall by the military due to their anti-war views, the Lawrences left England permanently in 1919 to live abroad, travelling to Australia, the US, Mexico, France, and Italy, where Lawrence died in 1930. Frieda remarried in 1950 and died at their Taos ranch, New Mexico, in 1956.

Feigel moves on to Lawrence’s views on religion and the apocalypse, subjects that drew him to ancient Mexican traditions for secular solutions to his notion of Christianity’s failure; and to his embrace of nature, accepting its “strangeness and destructiveness even as he celebrates it”.

Comfortable at both church and synagogue, Feigel says this side of Lawrence enabled her to recover the process of prayer, and accept the contradictions in his rejection of democracy in favour of a kind of “aristocracy of the elite”, that people are not born equal, and other largely unfashionable notions.

“I want literature and culture to open up a space where it’s possible to be passionately polemical, whether rightly or wrongly, or a Lawrentian mixture of the two, without feeling boxed in by each other’s voice,” she states.

Her year of ‘living with Lawrence’ left her hopeful “that I can find a way to live with contradictions while still finding truths that I can believe in enough to live by”. This is not likely to generate similar emotions among readers but it’s persuasive enough to make you want to turn back to Lawrence to see what you missed the first time.

Look! We Have Come Through! Living with DH Lawrence, by Lara Feigel (Bloosmbury).

Nevil Gibson is a former editor at large for NBR. He has contributed film and book reviews to various publications.

This is supplied content and not paid for by NBR.

Sign up to get the latest stories and insights delivered to your inbox – free, every day.