Kiwi writers explore Russian experience

Two novels provide insights into the Cold War and after.

NBR columnist Nevil Gibson speaks with Fiona Rotherham.

Two novels provide insights into the Cold War and after.

NBR columnist Nevil Gibson speaks with Fiona Rotherham.

Russia’s decision to sanction a further 32 Kiwis this week does not reflect the long-standing relationship between the two countries. The use of sanctions against individuals at this scale – New Zealand has hundreds on its list of banned Russians – is a relatively new diplomatic tool.

The mayors, columnists, and others in the latest list were not members of the diplomatic corps, public service or government, as is usually the case; they had supported or expressed criticism of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine on February 24.

This is a new twist to the historic ties, which in the 20th century started with the formation of the Communist Party of New Zealand in 1921 in the wake of the Bolshevik Revolution. It was initially part of the Australian party and became an autonomous affiliate of the Comintern in 1928.

While the party’s ideology and membership remained a minority faction in the labour movement and academia, its political influence was sufficient for the wartime Labour government to open a legation in Moscow in 1943.

It was one of only a handful of overseas posts in the fledgling foreign service, which had three in the US, including one at the UN in New York. The Moscow presence did not survive the early period of the Cold War, with the National government closing it in 1950, only for Labour to reinstate it as an embassy in 1973.

Mindovsky House, built in 1903, was the New Zealand Embassy in Moscow from 1973-2015.

Public interest in the Soviet Union from the 1930s had overcome the ‘Russophobia’ invasion fears that were a feature of the late 19th century. But – without any economic relationship, except for a brief Ladas for butter deal – the ties were limited to ‘friendship’ societies and cultural events.

New Zealand diplomat Gerald McGhie, a former ambassador in Russia, noted the Ministry of Foreign Affairs learned little from its 40 years of running the Moscow post. (His account is included in an authoritative collection of essays listed in the recommended reading below.)

Radical change

The post-Soviet era from the 1990s produced radical change, with Russia opening its borders to foreign travellers and the promise of economic prosperity bringing democratic reforms. That proved elusive, at least for Russia and most parts of the former Soviet Union except those closest to Europe.

In the past week, as a warmup to a daunting new 850-page biography of Vladimir Putin, I turned to the insights of two New Zealand novelists who have set stories in the Soviet Union and Russia.

Sarah Quigley in Berlin.

Sarah Quigley’s The Conductor (2011) is a fictional account of an event that has produced a dozen or more books, including two recent non-fiction titles. This is about composer Dmitri Shostakovich’s Seventh Symphony, which he started during the siege of Leningrad that lasted from 1941-44, and was performed there on August 9, 1942, as a morale booster and symbol of defiance to the Nazi invaders.

The microfilmed score was also smuggled to the West where it was performed in New York a few weeks earlier with similar purpose. At the time, Shostakovich was considered one of the world’s greatest living composers. At 75 minutes, and Shostakovich was a stickler in his instructions for conductors, the symphony was also one of the longest.

Quigley, who is based in Berlin and has published five other novels, focuses her attention on a small group of Leningrad’s musical fraternity. The title refers to the conductor of the city’s second-string Radio Orchestra, which stayed in the besieged city after the Philharmonic had relocated to Siberia.

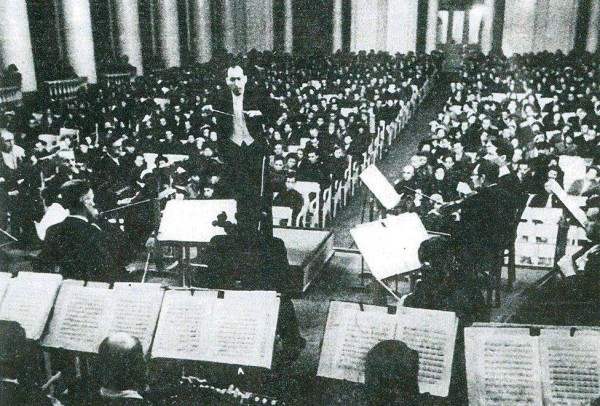

‘The Conductor’ Karl Eliasberg at the Leningrad concert on August 9, 1942.

Midway through the composing, and several months into the siege, Shostakovich and his family were evacuated from Leningrad to the safety of Kuibyshev (now Samara), where the symphony was first performed on March 5, 1942.

Varying interpretations

Its importance in the history of music has long been debated, with interpretations running from Stalin’s own view to its reception in the West. Though Quigley’s provides the reader with some technical details, it is her vivid characterisations, descriptions of the siege’s human toll, and the desperation of its emaciated citizens that stand out.

I will spare readers the terrible conditions in which the Radio Orchestra prepared for their concert, which was broadcast live and also heard through loudspeakers around the city. Intelligent conversations occur throughout the novel, such as one musician noting the paradoxes and contradictions affecting the lives of all Russians, including Shostakovich himself.

“Think of the music that would never have been written if he hadn’t been willing to compromise. To duck for cover when necessary, strut when commanded, and steer the fine line between integrity and common sense.”

As the city was battered daily by German bombers and food reduced to soggy bread made of wheat found dumped in water, Shostakovich continued his work.

“Anything composed in response to such extreme circumstances is a complex thing … It’s miraculous to compose a symphonic work of this scale in the middle of such hardship,” another colleague says.

Reading this today you can’t help but think of battered Ukraine and the irony of Russians being the perpetrators.

Rosetta Allan in St Petersburg during her writer's residency.

Rosetta Allan’s The Unreliable People (2019) is also inspired by real-life events, though the story and characters are fictional.

It is set in three time periods, the earliest being 1937, when thousands of ethnic Koreans were deported from eastern Siberia to central Asia, where they were ordered to continue their rice-farming in barren lands.

Work ethic

Faced with the expansion of the Japanese empire, Stalin distrusted these “unreliable people”, as the Koryo-saram (Koreans) were known. But their work ethic enabled the survivors of the “ghost trains” – so-called because of the deaths involved – to build thriving communities of some 500,000, who are today spread throughout seven of the former Soviet republics.

The second time period is 1974, when an infant Koryo-saram is abducted from her home in Kazakhstan and taken by train to Vladivostok. But the kidnapper, who turns out to be her aunt, has a change of mind mid-journey and sends the child back.

The final period is the mid-1990s, when the girl is an arts academy student immersed in the post-perestroika era of Russian youth exploiting their freedoms just like their equivalents in the West. This includes experimentation in artistic expression as well as in their private lives.

Allan weaves her small cast of characters into a story with embellishments that are the hallmark of modern creative writing courses. These include ancient Korean legends and dances, sex trafficking and orphanages for radiation-deformed babies, nonconformist art installations, and a non-binary person who claims to be the result of a brother-sister merger in the womb.

In contrast to Quigley’s linear narrative, with dialogue in conventional quotes, Allan writes in reported speech, laden with descriptive similes that add little to an intriguing tale that overcomes its dependence on coincidences.

These flourishes are based on extensive research, including the author’s three weeks in Russia as the first New Zealand writer at the St Petersburg Art Residency, which is in a building that also houses the Centre for Nonconformist Art.

Her time did not include an ability to master the language, though it did inspire her to write poetry. You learn a lot about the city’s layout and features, something Quigley can afford to ignore. Allan has separately written she plans to return. This is a hope that must remain on hold, not just for Allan but all others to whom Russia holds a strong fascination.

Disclosure: Nevil Gibson visited Moscow and Vladivostok for a week as a government-invited journalist in September 1990. In the following year, Mikhail Gorbachev announced the dissolution of the Soviet Union.

The Conductor, by Sarah Quigley (Vintage).

The Unreliable People, by Rosetta Allan (Penguin).

Recommended reading:

Lenin’s Legacy Down Under: New Zealand’s Cold War, edited by Alexander Trapeznik and Aaron Fox (Otago University Press, 2004).

Leningrad: Siege and Symphony, Brian Moynahan (2014).

Symphony for the City of the Dead, MT Anderson (2017).

Nevil Gibson is a former editor at large for NBR. He has contributed film and book reviews to various publications.

This is supplied content and not paid for by NBR.

Sign up to get the latest stories and insights delivered to your inbox – free, every day.