Julia’s world: The heroine of Orwell’s ‘Nineteen Eighty-Four’

A feminist makeover for the world’s most famous dystopian novel.

Julia, by Sandra Newman.

A feminist makeover for the world’s most famous dystopian novel.

Julia, by Sandra Newman.

The annual Booker prizes for literature are still a reliable guide to the best fiction in any year.

The latest winner, for 2023, was Irish writer Paul Lynch’s dystopian novel Prophet Song about a woman’s struggle to protect her family as Ireland collapses into totalitarianism and war. Lynch was a popular attraction at this year’s Auckland Writers Festival.

Germany’s Jenny Erpenbeck last month won the International Booker Prize for Kairos, about a love affair between a 19-year-old and a married writer in his 50s.

It has a dystopian flavour because it’s set in 1980s East Germany, where Erpenbeck lived until the Berlin Wall fell when she was in her mid-30s. (She shared the prize with Michael Hofmann, the unmatched authority in translating German to English.)

One critic, John Powers, describes their affair as “something of a metaphor for East Germany, which began in hopes for a radiant future and ended up in pettiness, accusation, punishment, and failure”.

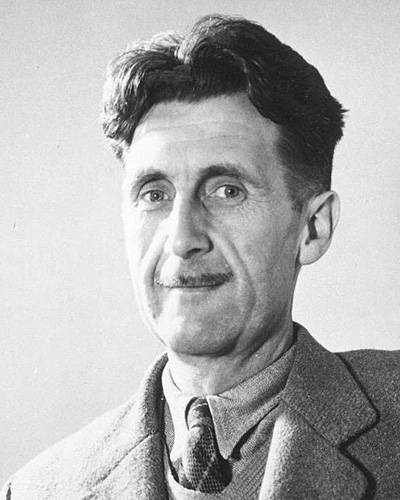

Which brings us to the most famous of all dystopian novels, George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four, published this month in 1949, six months before the author’s death.

Orwell is undergoing a modern revival, with the continuing relevance of his themes, mirrored in today’s authoritarian super-states of Russia and China in a world mired in the kind of endless warfare waged by the Islamist state of Iran.

These obvious parallels have been enhanced by feminist interest in Orwell’s private life, said to reflect his misogynist streak. Leading the pack is Wifedom, by Anna Funder, who also spoke to a packed audience at the Auckland Writers Festival.

Sandra Newman.

This has been complemented by Sandra Newman’s Julia, a reimagining of Nineteen Eighty-Four as experienced by Winston Smith’s lover, Julia Worthing (she did not have a surname in the original).

It’s a daring work, written using Orwell’s Newspeak vocabulary and closely following the story of Winston, a rewriter of archival stories for the Ministry of Truth, and Julia, who fixes the machines that churn out approved books for the citizens of Oceania. It’s one of the world’s three warring super-states and follows the doctrine of Ingsoc (English socialism).

American-born Newman, 58, spent her university years in the UK, enabling her to recreate the recognisable English setting of Airstrip One, a city resembling 1940s London during the Blitz. Newman previously wrote five novels, some with dystopian futuristic themes, but none had earned the praise of Julia. However, her third, The Country of Cream Star, was nominated for both the Folio Prize and the Bailey’s Women’s Prize for Fiction in 2015.

She was urged to write Julia by her agent with the support of the Orwell Estate. It was a concept that works brilliantly and has already been snapped up for a movie adaptation.

Julia plays a critical but relatively minor role in Nineteen Eighty-Four, and this is reflected in the two movie adaptations in 1956 and 1984. In the first, she becomes Winston’s girlfriend and is played as a 1950s blonde bombshell by Jan Sterling to Edmund O’Brien’s overbearing and imposing Winston.

Suzanna Hamilton and John Hurt in Michael Radford’s ‘1984’.

In the 1984 version, John Hurt is a more physically convincing Winston and Julia, played by Suzanna Hamilton, is a more worldly brunette. The physical side of their affair is much more explicit.

Newman takes this further by giving Julia a backstory that makes her sexually aggressive toward Winston and an instigator of their affair. Her motives and background add a strong feminist element to a character who has carefully chosen her machine fixing job to give her options that most other women, as well as men, don’t have under Big Brother.

Apart from Winston, she has easy access to other more superior males, such as O’Brien, said to be the leader of a resistance group to Big Brother. She is willing to take more risks than the older and cautious Winston, who keeps his emotions under control and his thoughts to a secret diary.

Julia’s expanded character is far more interesting, though this bulks out the story by a third more than Orwell’s original, which runs to about 250 pages compared with Newman’s nearly 400.

George Orwell.

She also provides more retrospection than Orwell’s rushed manuscript of 75 years ago, while avoiding the anachronisms. The surveillance technology, for a start, is more sophisticated than Orwell could imagine in today’s Russia and China.

Erpenbeck reminds us that the former German Democratic Republic was Newspeak at its best and the Stasi perfected the means for children to dob in their parents for thought crimes.

The digitally based internet and artificial intelligence, not imagined by Orwell or mentioned by Newman, are the perfect weapons for “vaporising” (her word) in today’s age of “cancelling” to create “unpersons” and churn out books by machine.

It’s no stretch to see a parallel in Big Brother’s omnipresent screens that observe everyone’s lives and today’s handheld devices. Orwell’s constantly circling helicopters are today’s drones.

Julia is champion of the Anti-Sex League, Big Brother’s attempt to break down romantic attraction between the binary sexes and put Party loyalty ahead of families. Yet she stalks mating partners and uses a pill to fulfil urges as men do with Viagra.

When Julia falls pregnant to Big Brother, she becomes a solo “trad wife”, as does her best friend, a new character called Vicky. In a further twist, when Julia and Winston separate after betraying each other under torture at the House of Love, the story moves on from Orwell’s downbeat ending to a even more shocking climax where Julia reunites with Vicky.

Orwell was a socialist with fears of how it would be corrupted by power. Newman gives this a feminist twist in a comment to Julia by her mother, a onetime revolutionary idealist who fought for Ingsoc before it became the patriarchal and totalitarian regime of Oceania.

“It wasn’t about Big Brother then, or any particular man – that was rather the point, I thought. But once they had power – well, then it was a throne and all fought for the throne.”

If your memory of Nineteen Eighty-Four is a little rusty, this highly relevant and exciting novel will more than restore it as well as freshen Orwell’s precautionary vision of a collective society.

Julia, by Sandra Newman (Granta Books).

Nevil Gibson is a former editor-at-large for NBR. He has contributed film and book reviews to various publications.

This is supplied content and not paid for by NBR.

Sign up to get the latest stories and insights delivered to your inbox – free, every day.