Intrepid internet hunter for the truth

ANALYSIS: Bellingcat founder tells how he exposes disinformation from open sources.

NBR columnist Nevil Gibson speaks with Fiona Rotherham.

ANALYSIS: Bellingcat founder tells how he exposes disinformation from open sources.

NBR columnist Nevil Gibson speaks with Fiona Rotherham.

The Disinformation Project no doubt started with good intentions – to alert people during the Covid-19 pandemic that scepticism about immunisation could be a public danger.

We now know that scepticism became a powerful political force, exacerbated by anti-vaxxers being mandated from their employment in the lockdowns.

Many were in trusted public service jobs such as healthcare, teaching, the military, and police. It led to the Government being seen as an agent that opposed free speech and dissenting opinions.

Instead of being restricted to the scientific debate over medical ethics, the Disinformation Project became associated with the wider cultural wars. These ranged from the Christchurch Call’s attempts to police the internet, to advocacy of Critical Theory in areas such as race, gender, colonialism, and other left-wing causes.

For its critics, the Disinformation Project proceeded down the same rabbit hole it accused its enemies on the ‘alt-right’ of doing: that disinformation was a tool to seduce people into extreme views and actions, potentially leading to acts of terrorism.

Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern and MC Stacey Kirk at a Christchurch Call summit on May 15, 2021. Photo: Mark Tantrum/MFAT

The muddying of language didn’t help, as the meanings of disinformation and misinformation became confused or conflated.

A while back, I reviewed two books relevant to this issue. One was Thomas Rid’s Active Measures, a history of disinformation and political warfare. The other was Cynical Theories, about the origins of cancel culture and the disappearance of open debate of ideas within universities.

Rid’s definition still holds: “The goal of disinformation is to engineer emotion over analysis, division over unity, conflict over consensus, the particular over the universal.”

He goes on to explain how disinformation exploits the difference between truth verified by facts and those based on belief. “The desired effect is to drive wedges between countries, ethnic groups, and even individuals, while undermining trust in authorities and institutions.”

As to its origins, Rid traces this back as an ideological tool of Soviet communism. During the Cold War, it was embodied in imaginary neo-Nazi organisations to foment antisemitic attacks in several countries, a fake Ku Klux Klan letter warning African and Indian UN delegates in 1960 about racial threats in New York, and a false African-America front that cast doubts on US aid in Africa.

Martin Sixsmith’s psychological history of the Cold War, The War of Nerves, devotes an entire chapter to disinformation and the Soviet aim of undermining the confidence of people in the West of their democratic institutions.

His account of fake neo-Nazi and other extremist organisations compares with today’s internet, where similar tactics are employed, but no longer in the cause of communism.

Bellingcat founder Eliot Higgins.

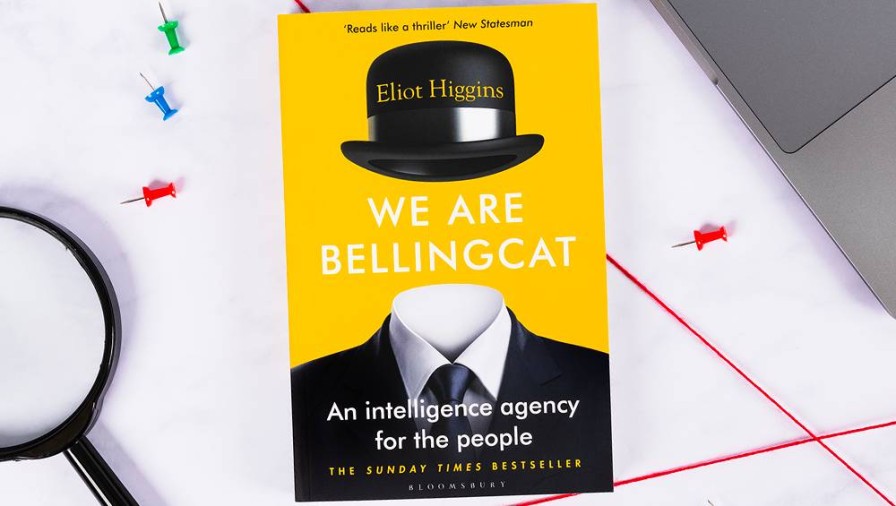

These are revealed in We Are Bellingcat, Eliot Higgins’ account of how he founded a private, open-source intelligence agency aimed at exposing ‘fake news’ and warning the news media, in particular, not to fall for “shit-posting” – the practice of exaggerating content designed to distress and mislead less savvy internet users.

A Bellingcat investigator, using techniques honed from sorting truth from fiction in the Syrian civil war and the shooting down of Malaysian flight MH17 in 2014, wrote a brief analysis shortly after the Christchurch mosque attacks in March 2019.

His paper, ‘Shitposting, Inspirational Terrorism and the Christchurch Mosque Massacre’, concluded that the killer’s manifesto was intended to dupe the news media and manipulate the public. The author, Robert Nelson, describes the online ramblings as being full of “memes and in-jokes” addressed to a “very specific crowd”.

“The fact that someone planning mass murder wanted to crack jokes with his online buddies is hard to comprehend,” Higgins states. “But this brand of ‘humour’ is familiar to those of use who grew up with message-board culture … For fascists, callous ‘humour’ had a secondary purpose. It was a way to camouflage transgressive ideas, and edge them into the mainstream.”

Higgins says Nelson’s further efforts in exposing the nature of these sites has helped shape public opinion to be more wary of ‘fake news’ than might otherwise be the case. This suggests the worst the Disinformation Project can do is to over-egg the impact of such views.

Furthermore, it should not accuse those holding mainstream opinions of becoming gullible victims and therefore capable of illegal actions, which is what some of its critics have alleged.

Bellingcat’s origins as an agency exposing disinformation through open rather than covert sources are far removed from attempts to censor or suppress views that aren’t tied to the agenda of a government or some ideology.

Instead, it was the curiosity of someone who realised the wealth of information hidden from plain sight in social media postings, leaked databases, and satellite maps.

“Paradoxically, in this age of online disinformation, facts are easier to come by than ever,” Higgins states. He launched his own blog, Brown Moses, which challenged claims by the likes of Moscow’s RT channel. The backgrounds in dubious footage were extensively checked against Google maps and other sources for verification.

His exposés were soon noticed by media such as The Guardian and the New York Times, which put his story about the Saudis funding the Free Syrian Army to buy anti-tank weapons from Croatia on the front page.

That was followed up by the confirmation of chemical weapons used by Syrian government troops, despite their denials. Famed US correspondent Seymour Hersch was one who fell for the false news that the gas had American sources.

Bellingcat confirmed the use of these chlorine aerial rockets in Syria.

The blog evolved into Bellingcat just three days before its biggest success: confirmation that a Russian Buk missile system shot down the Malaysian airliner in Ukraine air space.

The weapon was traced to Russia’s 53rd Anti-Aircraft Missile Brigade, based in Kursk, through tracking social media posts of the Russian soldiers involved, as well as pictures of the unit’s travels across the border into Russian-occupied Ukraine.

Bellingcat found this dash-cam photo of the Buk missile launcher.

The Salisbury poison attack on former Russian spy Sergei Skripal and his daughter Yulia earned more global headlines, as Bellingcat was able to name the assassins’ real identities through searches of Russian databases. Similarly, Bellingcat was able to track the movement of individuals involved in the poisoning of Russian opposition politician Alexey Navalny.

The detail of these case studies is fascinating, as is the growth of Bellingcat’s influence. It hopes to have a team of 100, half of them fulltime staff and half regular contributors, by 2030, with information published in six languages. It also has plans to widen its activities to Latin America and Africa.

Higgins says funding comes from crowd-sourcing and grateful customers, which include the Western news media. Higgins has turned the organisation from a loosely run volunteer outfit into a charitable foundation with a structure more suited to handling a substantial, professional human resource.

He sees a big use in the future of artificial intelligence to scan the vast amount of data available online, reducing the human workload, while focusing on the activities of government-backed hackers that use traditional scam or ‘phishing’ tactics. The disinformation players of the alt-right and alt-left Counterfactual Community also remain a priority target.

We Are Bellingcat: An intelligence agency for the people, by Eliot Higgins (Bloomsbury).

Nevil Gibson is a former editor at large for NBR. He has contributed film and book reviews to various publications.

This is supplied content and not paid for by NBR.

Sign up to get the latest stories and insights delivered to your inbox – free, every day.