Imperial lamb: British to the backbone

How marketers sold colonial products in the Home country.

NBR columnist Nevil Gibson speaks with Hamish McNicol.

How marketers sold colonial products in the Home country.

NBR columnist Nevil Gibson speaks with Hamish McNicol.

Attempts to rebut the positive contributions of empires to world history have generally failed to gain traction. Monty Python summed it up in the Life of Brian sketch: “What have the Romans ever done for us?” Turns out they provided aqueducts, sanitation, roads, irrigation, medicine, education, wine, public baths, safety, order, and peace.

A good scholarly guide to how empires have shaped the world is Samir Puri’s The Great Imperial Hangover (2021), which covers the triumphs and tragedies of the Chinese, Ottoman, Mughal, Russian, and Western European empires.

Puri was born to Indian parents in colonial Africa and is a scholar at the International Institute for Strategic Studies in Singapore. He spent an early part of his career at the British Foreign Office. He was part of a diplomatic mission after Russia’s first invasion of Ukraine in 2014 and an academic at King’s College London and Johns Hopkins in the US before moving to Singapore.

With that experience and worldview, he would be surprised to find a New Zealand government-funded arts organisation could label the works of Shakespeare as part of an “imperial canon” and had no role in “decolonising Aotearoa”.

Shakespeare (1564-1616) died more than a century before the first signs of a British Empire, which didn’t emerge until after the Seven Years War, 1756-63, and was first established in North America, the Caribbean, and India.

Until then, the putative empire existed only as a maritime commercial network. These facts of economic history are largely irrelevant to those who want to fit the past into a contemporary framework.

Some have pointed out the post-modernist thinking behind the arts funders’ decision to wipe out the “whole idea of a materially and imaginatively recoverable past – a past with the power to influence both the present and the future,” as Chris Trotter put it.

“The post-modernists hate the idea of History as both tether and teacher – fettering us to reality, even as it reveals the many ways our forbears have responded to the challenges of their time.”

In this scenario, Shakespeare’s works must be downgraded and rejected because they connect us to the past and, like all the other great cultural achievements, reveal timeless insights into the human condition.

Kenneth Branagh as Boris Johnson in This England.

No better example of this was demonstrated in Sky UK’s excellent six-part miniseries This England, in which Boris Johnson, played by Kenneth Branagh, constantly quotes Shakespeare while dealing with political pressures in the public arena as well as in his private life.

It is in this context that I read Selling Britishness: Commodity Culture, the Dominions, and Empire, by Felicity Barnes, a senior lecturer at the University of Auckland and specialist in colonial history. This is a colourful account of how, from the mid-1920s, the Western world embraced the consumer society and how three settler colonies of the British Empire (Australia, Canada, New Zealand) marketed their goods in the ‘Home’ country.

But this goes further than the consumer-led democratisation of society that followed Thorstein Veblen’s analysis of the Gilded Age of the late 19th century or the post-World War I marketplace, in which a variety of goods competed to attract buyers. History is no longer just a record of economic transaction but has a cultural context.

“Consumption is a … lightning rod for new ideas of self and subject, of gender and class, of nationality and community, of race and place,” to quote from Getting and Spending (1998). In this broader picture, the three Dominions created an “imperial success story” – imperial being a synonym for ‘Britishness’.

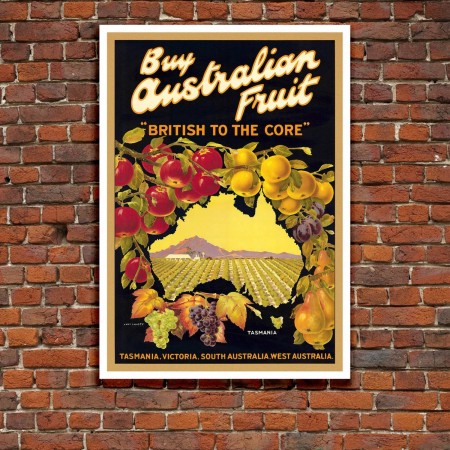

“New Zealand lamb and dairy products filled British shop windows; specialty Canadian ‘empire’ shops plugged wheat, apples, bacon and even macaroni; and Australian fruit and butter appeared on British cinema screens,” Barnes writes.

Dr Felicity Barnes. Photo: Elise Manahan

Marketing ploys included birthday cards from ‘Uncle Anchor’, aerial banners reading ‘Canada Calling’ and touring Australian cricketers extolling the virtues of Antipodean apples.

The advertising industry boomed and budgets in Britain nearly doubled during the interwar period from £31 million in 1920 to £59m in 1938. The industry attracted New Zealand’s leading agency, Ilott Advertising, which set up a London branch in 1926. It closed in 1967 as its role declined and so did the sale of British consumer goods in New Zealand.

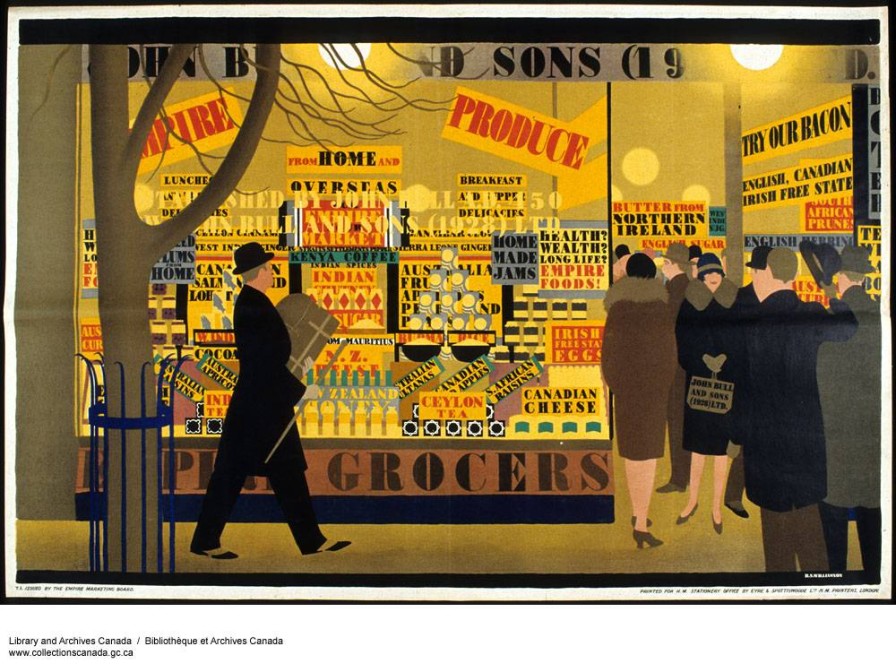

Empire Marketing Board poster in the 1920s.

A key organisation was the Empire Marketing Board, a British government-funded initiative that economic historians described as ineffective in its basic role. But to cultural historians, it is a goldmine because it successfully promoted the idea of an empire that was “racist and gendered”.

The board was wound up in 1933 after seven years, marking an end to free trade in the global economy. The rise of protectionism was to blight world progress until the tariff-reducing Gatt in 1947 and subsequently the World Trade Organisation in the 1990s.

After 1932, Britain had adopted ‘imperial preference’, which had little impact on the Dominions’ marketing campaigns. New Zealand’s promotion of dairy products was far more effective than the EMB’s efforts.

These campaigns shared a form of identity, Barnes notes. “Australian sultanas, Canadian cheese, and New Zealand lamb were not only all ‘British’, they were ‘British’ in the same way.” Consumers didn’t respond to notions of Empire, rather they preferred a “cosy, domesticated version of Britishness”. Hence Australian butter was “all British” and New Zealand lamb was “British to the backbone”.

Australian fruit was an ingredient in the King’s Christmas cake.

One of the EMB’s successes was the ‘King’s Christmas cake’, launched in 1927. It contained Australian dried fruit, Canadian apples, and New Zealand suet, among other ingredients. One displayed at Australia House weighed in at three-quarters of a ton.

The three Dominions all depended heavily on the British market for their export products, whether consumer oriented or commodity products such as wheat, wool, and cloth. Britain took 80% of New Zealand exports from 1901-39, while for Canada (which also had the large US market next door) it was 33-50%, and 40-50% for Australia.

The British market was sophisticated and no pushover for producers. The Dominions had to compete against other countries as well as wholesale and retail-level buyers who wouldn't hesitate to reject stale or shoddy goods.

It was the same for British manufacturers, despite popular beliefs, according to Barnes: “Newer research [by historians] has challenged the assumption that Britain’s colonies acted as ‘featherbeds’ for poor British products, concluding instead that ‘empire markets were frequently demanding and difficult’ …”

Trade was disrupted by spats such as the 1934 attempt by Australia to protect its small cotton industry. Grocers in the textile towns of Bolton and Lancashire responded with boycotts of Australian butter.

Barnes identifies racist overtones in the “complex interplay of marketing, hygiene and whiteness” in the promotion of fruit and the lack of Indigenous elements, except in tourism.

“Dominion commodity advertising made little use of Indigenous motifs in its designs, and even less of Indigenous people.” An exception was Australia’s use of the boomerang.

Gender issues are also not overlooked. An Australian white male standing against a sun-drenched landscape was prominent in promoting the fruits of fertile, virgin land, echoing the the explorers who preceded the settler-farmers.

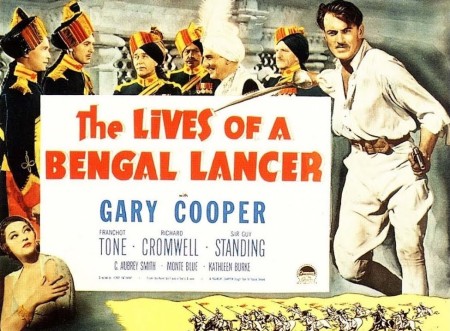

Gary Cooper starred in Britain’s most popular movies in 1935.

Imperial themes ran hot in the cinemas, the main form of popular entertainment in the 1930s. The Lives of a Bengal Lancer (1935) outgrossed Fred Astaire’s Top Hat in British theatres. The Dominions provided the promotional shorts supporting the feature programme.

These came from the equivalents of the New Zealand National Film Unit, and included The Meat We Eat (1931), sponsored by the NZ Meat Producers Board. Another, Meadow to Market, began with Māori in traditional costume cooking on an open fire, emphasising the progress to modern industrial processes.

“The linear sequence of process film meant that colonisation could be reinterpreted and compressed, packaged away in a few frames of film while the audience’s attention was redirected to bucolic farming scenes.” This also applied to the shift from farm to factory and from “pioneering days to the present”.

While this academic framework is an essential part of scholarship today, the rich detail and anecdotes from the past are a valuable contribution to wider knowledge of how New Zealand earned a living from exporting food. The book has extensive notes, sources, and index. The cover, by the way, is Frank Newbould’s The Good Shopper (1935) and hangs in the Manchester Art Gallery, which has a world-leading collection of industrial paintings.

Selling Britishness: Commodity Culture, the Dominions, and Empire, by Felicity Barnes (Auckland University Press).

Recommended reading: The Great Imperial Hangover, by Samir Puri (Atlantic Books, 2021),

Nevil Gibson is a former editor at large for NBR. He has contributed film and book reviews to various publications.

This is supplied content and not paid for by NBR.

Sign up to get the latest stories and insights delivered to your inbox – free, every day.