How today’s wars are won and lost

ANALYSIS: Two military experts, including former CIA director David Petraeus, survey the past seven decades of world conflicts.

WATCH: NBR columnist Nevil Gibson speaks with Calida Stuart-Menteath.

ANALYSIS: Two military experts, including former CIA director David Petraeus, survey the past seven decades of world conflicts.

WATCH: NBR columnist Nevil Gibson speaks with Calida Stuart-Menteath.

In early 2020, when Western intelligence warned that Russia was preparing an invasion of Ukraine, few European politicians considered such an action was possible. Others, too, thought such a conflict was unlikely.

When the warnings turned into reality in late February, I was told mid-year by New Zealand’s leading foreign policy commentator that it would be “over by Christmas”.

This reaction was understandable. No-one likes wars in an age of 24-hour TV coverage that thrives on the plight of victims. The most-heard reaction is to call for ceasefires to prevent a “humanitarian crisis”.

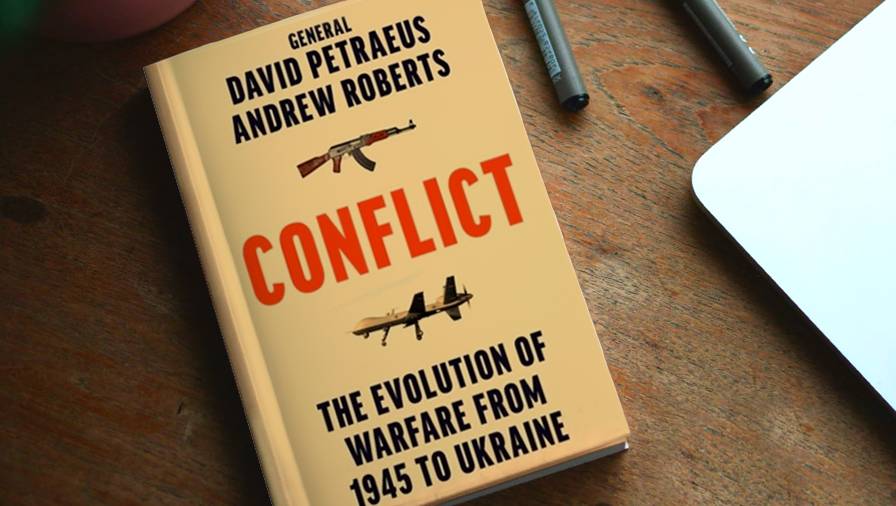

This is a profoundly misguided reading to how conflict has evolved in modern times. Much-different scenarios are presented in Conflict, a history of warfare since 1945 by two of the world’s best military minds, retired US General and former CIA director David Petraeus and UK historian Lord Andrew Roberts, biographer of Napoleon and Churchill, among others. It runs to more than 500 pages, including nearly 100 of maps, notes, and sources.

General David Petraeus.

Lord Andrew Roberts, author of ‘Napoleon’.

Though their account ends at the Russian invasion of Ukraine, it is relevant to the war that has hogged the headlines for the past four weeks – Israel’s response to a surprise attack by the Gaza-based Hamas, a group in the jihadist tradition of Al Qaeda and Islamic State.

Significantly, it occurred on the 50th anniversary of the Yom Kippur war of 1973, when Israel was also caught napping on a Jewish religious holiday.

Earlier, in 1967, Israel scored a comprehensive victory over invading Arab forces in the Six-Day War. Petraeus and Roberts recall a statement by then president Chaim Herzog, who noted, “Israeli Command tended to credit itself with many other achievements that were in some cases more a result of Arab negligence, lack of coordination, and poorer command at the higher level, than of Israeli effectiveness.”

This over-rating of past successes has parallels with the October 7 attack, which also called into question the performance of Israeli intelligence. The difference was that the targets were civilians rather than military forces.

A woman at a Lisbon, Portugal memorial to fallen Israelis in the October 7 Hamas attack.

The authors observe: “Yom Kippur was a reminder that deterrence only works when it threatens overwhelming punishment.” That still applies today when, by 20th century standards, the world is largely peaceful at 3.5 deaths in 100,000 through war in 2022, compared with an average in the 20th century of 30 per 100,000.

After 1945, deterrence was provided by nuclear weapons. The two bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki weighed 14 and 20 kilotonnes respectively. Rapid development soon amounted to the equivalent of one million tons and the threat of mutual annihilation. Yet, under the nuclear umbrella, conflicts continue in several parts of Africa, the Middle East, Asia, and Central America (against drug cartels).

In the late 1940s and 1950s, wars were largely fought by nationalists or insurgents against imperial powers. Maoist Chinese communist forces fought for several years against those of Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek until 1948. Weakened by their fight against the invading Japanese, Chiang’s army was no match for Mao’s guerrillas backed by the Soviet Union.

An armistice was signed but no treaty officially declared an end to the Korean war.

Korea was the next theatre, as the anti-communist forces regrouped under the fledgling United Nations and fought the Chinese and Soviet-backed communists to a standstill. That was one case where a ceasefire occurred, an armistice was signed, but no formal peace treaty was made. Technically, the war is unresolved, leaving Korea divided between two hostile regimes.

The state of Israel was declared in 1948, with the UN supporting Jewish self-determination at the expense of the displaced Arab population. Events in Kashmir in 1948 paralleled those in Israel, with a Muslim majority seeking to join Pakistan but foiled by India, which still uses force to suppress the population.

From these mid-century wars, Petraeus and Roberts provide the three Rs of successful guerilla insurgencies: revenge for a real or perceived wrong; renown (for a cause) that gives meaning to their lives; and the desire to provoke a reaction from the enemy. A fourth R, religion, adds another potent ingredient to the mix.

These elements can work both ways. The British Empire-backed Malay Muslims fought a successful battle against an ethnic-Chinese communist uprising, while the Indo-Chinese and Algerian nationalists defeated the French imperialists.

The Cold War played an important role in these post-colonial wars. The best example was Vietnam, where the US and its allies fought unsuccessfully for more than a decade to resist communist control of the decolonisation process.

Prussian military theorist Carl von Clausewitz.

The failure was to ignore one of the precepts of the 19th century Prussian military theorist Carl von Clausewitz to politicians and commanders: that of establishing “the kind of war on which they are embarking; neither mistaking it for, nor trying to make it into, something that is alien to its nature”.

The lessons of Vietnam, recognised by Henry Kissinger and others, failed to be applied in Afghanistan, Iraq, and Syria, where insurgents scored highly on the four Rs. Petraeus provides excellent analyses of these wars, where the military action was initially successful but failed to be capitalised on in the political follow-up.

The complexities of Afghanistan defeated the Soviet occupiers in 1979 as the Americans provided superior technology to the mujahadeen. But, 22 years later, the ‘War on terror’ after the 9-11 attacks on New York and Washington DC failed to establish a government strong enough to repel the Taliban for a second time.

Amid these failures were successful examples of “overwhelming force” and high morale to defeat an enemy: the UK’s expulsion of Argentinian invaders of the Falklands in 1982; the Nato bombing of Serbia that ended the Balkans wars in 1995; and the hard-won defeat of the Islamic State caliphate in 2019.

In their conclusions, the authors say the world is not likely to see an end to major wars involving large conventional forces, much less an end to small-scale insurgencies, terrorist campaigns, and guerilla warfare.

High morale has been critical to Ukraine’s resistance to Russian invasion.

The Russo-Ukrainian war dispelled the notion that future wars will be resolved as quickly as the Gulf War of 1990-91. Like Israel, Ukraine cannot afford to lose an existential threat or be betrayed by poor leadership.

Just as important are the non-military objectives that complement and augment battlefield operations. The authors are aware that, despite their focus on conventional warfare, other forms of conflict persist. These include cyberwarfare; major criminal activities, such as the drug cartels in Mexico; and the use of information warfare, where the moulding of public opinion can be critical to maintaining or defeating morale.

Though they often start on the back foot, democracies have one advantage: dictatorships tend to crack under the stress of sustained war as they face a foe that has popular support, higher morale, and can muster larger resources in the long run.

Above all, the authors emphasise the role of deterrence and the need for the democratic world to remain vigilant in keeping the peace. It is hard for any book about warfare to be positive. But an understanding of how it is conducted in the past, present, and future is critical to greater understanding of modern realities.

Conflict: The evolution of warfare from 1945 to Ukraine, by General David Petraeus and Andrew Roberts (William Collins).

Nevil Gibson is a former editor at large for NBR. He has contributed film and book reviews to various publications.

This is supplied content and not paid for by NBR.

Sign up to get the latest stories and insights delivered to your inbox – free, every day.