How Bill Gates did it his way

A revealing look at the Microsoft co-founder’s childhood and early business years.

Source Code: My Beginnings, by Bill Gates.

A revealing look at the Microsoft co-founder’s childhood and early business years.

Source Code: My Beginnings, by Bill Gates.

Microsoft’s reaction to the trillion-dollar bite that Chinese AI company DeepSeek took out of the valuations of the tech titans was to quote a mid-19th century economist.

According to The Economist, Satya Nadella posted on X: “Jevons paradox strikes again! As AI gets more efficient and accessible, we will see its use skyrocket, turning it into a commodity we just can’t get enough of,” along with a link to the Wikipedia page for the economic principle.

William Jevons had observed that technological gains in efficient use of coal had led to the increased consumption in a wide range of industries. He argued that, contrary to common intuition, technological progress could not be relied on to reduce fuel consumption. But it did lead to increases in real incomes and accelerated economic growth, further increasing the demand for resources.

In the case of DeepSeek, which has claimed to be much cheaper and more efficient than existing AI systems, Nadella was suggesting the demand for data centres, Nvidia chips, and even nuclear power reactors would consequently also be greater.

Microsoft chief executive Satya Nadella.

This logic would have impressed Microsoft’s co-founder, William Gates III, better known as Bill, who had a similar vision for a computer on everyone’s desk at a time when they were large multi-million-dollar machines locked away in dust-free buildings.

The first of three planned volumes of his autobiography, Source Code, produced the same response in me as tennis star Andre Agassi’s Open (2009), one of the best of any books on sport. Most business autobiographies aren’t as revealing and are full of spin – not to mention clichés.

The brilliance of Open and Source Code is their self-effacing honesty, despite big egos. They are harsh critics of themselves but seldom blame others for their failures. Open was ghostwritten by Pulitzer Prize-winner JR Moehringer, while Gates has a list of acknowledgements to writers, researchers, and editors that rival the credits in a Marvel movie. The only thing missing is an index, which should be added to any future editions.

The result is a book that could rival Open’s one million copies sold, while not reaching the celebrity status of Barack and Michelle Obama (a combined nine million copies). My recommendation is that Source Code should primarily be read by parents with gifted but difficult children.

Gates did not become the world’s richest man for a couple of decades by accident or luck. But he was born in the right place at the right time. Mid-1950s America was booming in the post-World War II era, based on industrial progress and the opening of university study to service personnel.

Bill Gates snr, Mary Maxwell Gates, and Bill at his 1994 wedding.

His parents, William Gates snr and Mary Maxwell, were both brought up in Christian Science families that settled in Seattle. While the couple did not practice that religion, this wholly American denomination, founded in 1879, valued the primacy of the mental world and self-sufficiency to the point of rejecting some forms of medicine.

William snr, also known as Bill, came from a working-class background but he used his military service to gain a law degree. He established his own law firm, now called K&L Gates, advising on major business deals. He turned down the opportunity of becoming a judge so that it wouldn’t compromise Mary’s use of her business degree to advance a career in administration and charities. She came from a family of bankers and later was a director of several major financial companies, head of the United Way of America charity, and member of a university council.

They lived in a neighbourhood of heavily degreed lawyers, accountants, business owners, rocket scientists, and engineers. Boeing, the aerospace giant, was a big employer.

The Gates family had high hopes for their third Bill (or ‘Trey’ as they called him, the term for 'three' in cards) despite his difficulties in school. While obviously bright, he was disruptive in classes, obsessive in his learning, and lacked some social skills.

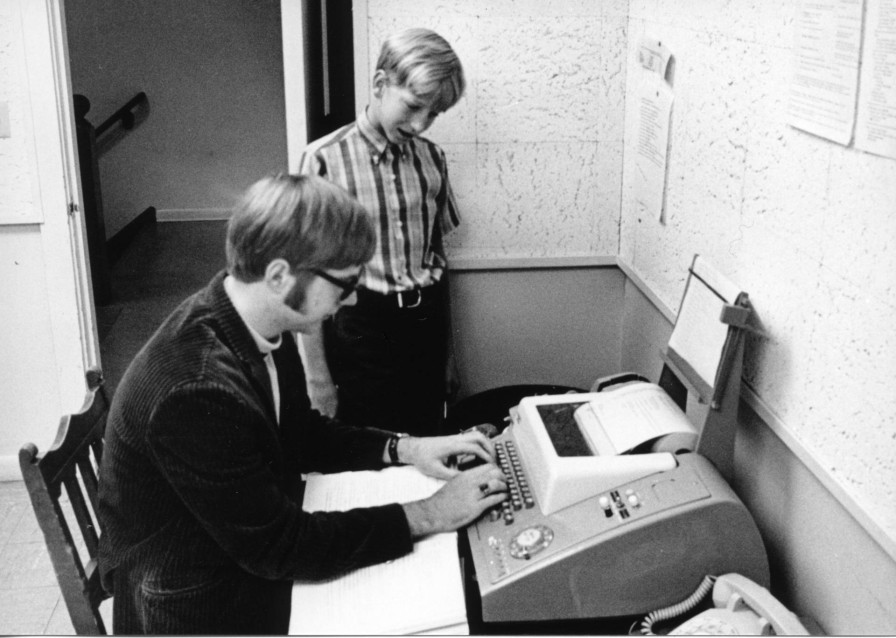

Bill Gates, 13, with Paul Allen, seated, at Lakeside. Photo: 1969-70 school yearbook.

His characteristic rocking motion while seated was an early habit. Today, those characteristics would immediately be recognised but not back then, as the young Gates progressed through to a private high school, Lakeside. It employed a lot of well-qualified male teachers.

The term autism is not mentioned in the book, though Gates has admitted as much in interviews. It did mean his parents and two sisters had to adjust to his unconventional behaviour, some of which Gates apologises for in retrospect. Much about this period of his life comes from the people he grew up with and help make the book so emotionally engaging.

Lakeside got its first DEC (Digital Equipment Corporation) minicomputer in 1968 when Gates was 13. It was the same year I started work in an industry that strongly resisted changes in technology.

While this held back my introduction to computers for many years, Gates and his handful of friends plunged into all-night coding sessions as teenagers. He climbed out his bedroom window late at night to work at a commercial bureau while it wasn’t in use.

It would be wrong to describe the young Gates as nerdy. He was no good at pure maths and spent a lot of time hiking in the nearby mountains, even if he used the time to do coding solutions in his head. He liked to drive fast and purchased a Porsche as soon as he could afford one.

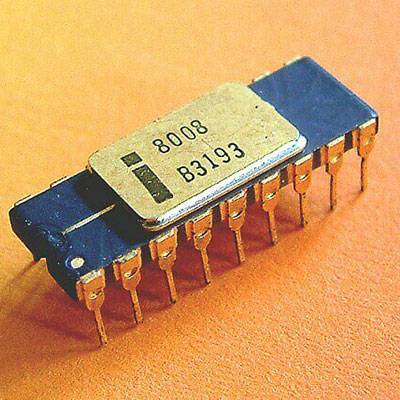

Intel 8008 microprocessor.

Gates and his closest collaborator, Paul Allen, believed micro-computers had the same disruptive potential for growth as DEC had delivered to mainframes, then dominated by IBM.

Intel’s invention of the 8008 chip for microprocessors led to the first machine that looked like a personal computer. The Altair was made by a startup called MITS but had limited functions and too many switches.

Gates, then 16, and Allen, 19, bought an 8008 chip for US$360 (US$2400 today), a big investment. But their idea of putting a Basic software program into the microprocessor soon made the Altair the hottest product for electronic hobbyists.

Allen got a job writing software at MITS, based in Albuquerque, New Mexico. Microsoft was already on its way, with Allen moving to DEC in Boston. Meanwhile, Gates was not far away, having chosen Harvard for his degree studies. His extra-curricular coding business almost got him expelled for illegally working on a top-secret machine provided by the US military.

Gates describes Microsoft's business plan as follows: “We could start small, like DEC did … expand, become consultants … all the while writing software for that new universe of microprocessors that Intel had recently pioneered.”

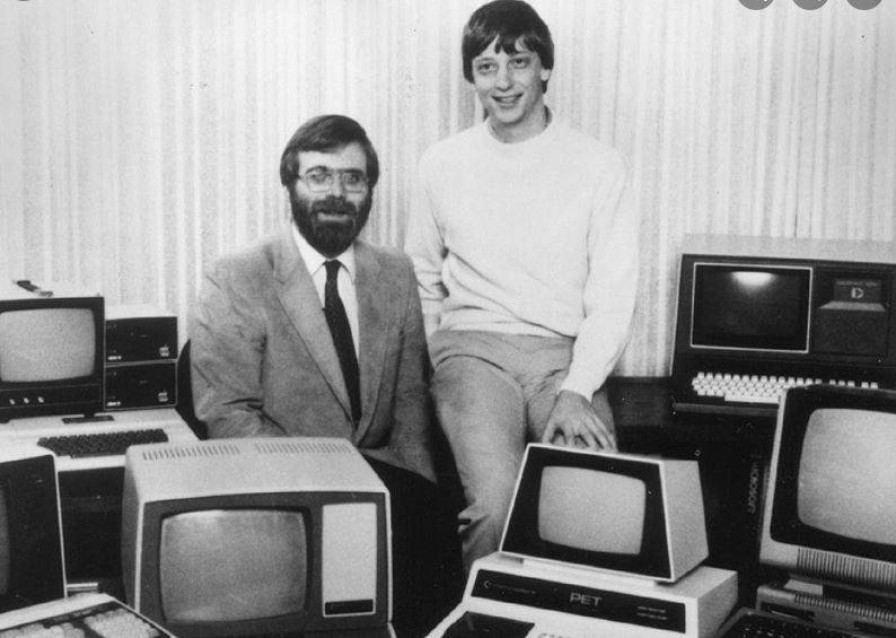

In their relationship, Allen was the visionary entrepreneur, full of ideas. Gates was the anchorman, with attention to detail and all that it took to run a business. This gave him a 60-40 share of what was to become the most valued company in the world.

But Microsoft remained a software company in an industry where hardware was king. It was dependent on MITS paying royalties, which it did only sporadically due to piracy, and other hardware suppliers also wanting programs. The breakthrough came with the Commodore PET 2001 and some hardnosed negotiations that finally ended the crippling association with MITS.

Paul Allen and Bill Gates with the Altair 8800.

The book closes in 1978, with Gates in his early 20s and undecided on his studies at Harvard. New clients such as NCR and Radio Shack were pleading for programmes. Gates squeezed back some of Allen’s shareholding to allow a new partner, Steve Ballmer. The small company of just 20-odd employees moved north to Seattle, just far enough from Silicon Valley to keep secrets.

Allen died in 2018 after quitting the company in 1983 because of a degenerative disease. Microsoft went public in 1986, Ballmer succeeded Gates as chief executive in 2000, and Nadella replaced him in 2014.

Gates is no longer the world’s richest man. In fact, he is down to 16th on the Forbes list at US$106.3 billion, but seventh on Bloomberg’s at US$164b. (The difference, according to Microsoft’s Co-Pilot, is that Bloomberg has only 300 billionaires on its list and updates them daily based on market data. Forbes has a larger list and incorporates other assets in its calculations.)

Microsoft remains a US$3 trillion business, just behind Apple at US$3.4tr as the world’s most valuable company. How that happened is part two of the Gates trilogy.

Source Code: My Beginnings, by Bill Gates (Allen Lane/Penguin Books).

Nevil Gibson is a former editor-at-large for NBR. He has contributed film and book reviews to various publications.

This is supplied content and not commissioned or paid for by NBR.

Sign up to get the latest stories and insights delivered to your inbox – free, every day.