Hollywood’s century of cinematic catastrophes

Filmgoers beware: Low-flying turkeys.

Box Office Poison: Hollywood’s story in a century of flops, by Tim Robey.

Filmgoers beware: Low-flying turkeys.

Box Office Poison: Hollywood’s story in a century of flops, by Tim Robey.

When the Walt Disney Company released a live-action remake of animated classic Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, it had already been branded a flop. This was not unusual, as word gets around that movie projects, some involving several hundreds of millions of dollars, are in trouble for various reasons.

The new version, called just Snow White, had raised several red flags, some related to Disney’s commitment to DEI (diversity, equity, inclusion) before it went out of fashion under President Donald Trump.

Snow White poster, with Gal Gabot and Rachel Zegler. Walt Disney Studios.

The eponymous heroine was no longer ‘white’ but a Latino actress, Rachel Zegler. Although live action means using real people rather than animated ones, the seven dwarfs were computer generated.

The pre-release publicity turned worse when the two female leads, Zegler and Gal Gabot (as the evil Queen), verbally clashed over the Gaza conflict. Before her screen career, Gabot was an Israeli beauty queen and had served in the Defence Force. Zegler sided with Hamas.

But a flop isn’t a flop until the figures come in. On a budget of US$250 million ($416.3m), a blockbuster movie needs an audience score of about 90% and to take at least US$100m in its first weekend if released globally.

Snow White fell short on both counts, as well as getting backhanded reviews that it wasn’t as bad as expected. But it was far from being a flop in the business definition.

Its latest box office performance is approaching US$200m worldwide, making it fourth among the 2025 releases but still some distance from being profitable. It failed dismally in China, where Disney’s The Little Mermaid – with an African American cast as the heroine – also met resistance from racially conscious audiences. The tariff war may mean the China market is now off-limits.

Snow White does not meet London's Daily Telegraph film critic Tim Robey’s definition of a flop in his clickbait book Box Office Poison, covering 100 years of Hollywood’s biggest financial disasters. He chooses 26 titles, starting with DW Griffith’s Intolerance (1916).

This epic, originally two four-hour films telling four stories over 2500 years of human history, made the biggest unadjusted loss of any Hollywood production until 1954’s 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea. It ended Griffith’s filmmaking career, as flops have done to dozens of others, several of which are recounted by Robey.

Daily Telegraph film critic Tim Robey.

They included, from the 1920s, the German director Joseph von Stroheim, whose Queen Kelly (1929) starring Gloria Swanson was never completed or released. His vision greatly exceeded his budget, a problem common to most flops. Von Stroheim continued his career as an actor.

Box Office Poison has a cupboard full of anecdotes embellished by schadenfreude. The most notorious in recent times was Cats (2019), a mixed live-action and computer-generated version of Andrew Lloyd Webber’s musical.

It had the makings of a train wreck from the get-go. Lloyd Webber was so traumatised that he bought an emotional support puppy so he could attend the New York premiere in the middle of the pandemic.

He requested dispensation from an airline, which asked: “Can you prove that you really need him?” He replied: “Just see what Hollywood did to my musical Cats.” Back came the response: “No doctor’s report required.”

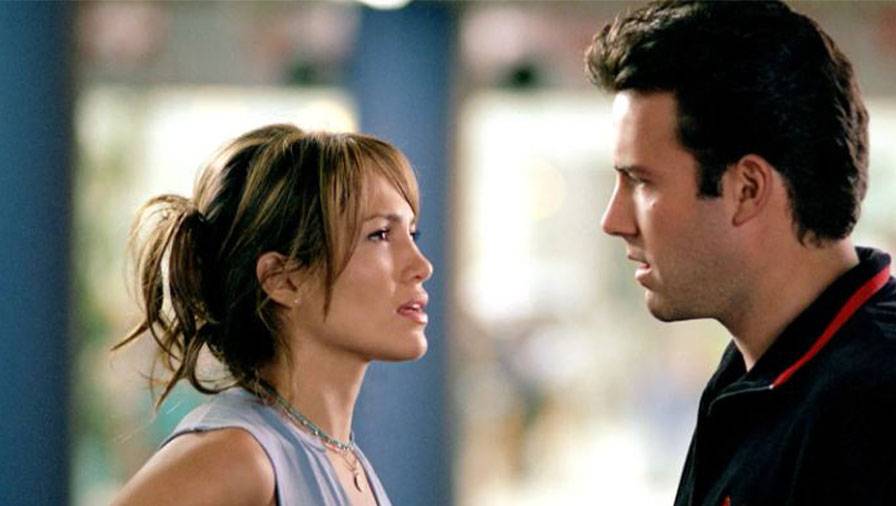

The director, Tom Hooper, never made another movie. The same fate befell Martin Brest, whose Gigli (2003) was one of the 21st century’s earliest flops. Most of the drama was in the off-screen affair, dubbed "Bennifer", between stars Ben Affleck and Jennifer Lopez. Robey blames director over-reach as well as a “faithless producer who promised him a final cut, was freaked out by bad test screenings, then strong-armed him into softening his film’s whole tone for a facile happy ending”.

Jennifer Lopez and Ben Affleck in Gigli. Columbia Pictures.

Most flops undergo similar interference when the product doesn’t meet the studio’s expectations. Warner Bros “panicked” when faced with Dan Aykroyd’s Nothing But Trouble (1991), a comedy-horror starring Chevy Chase and Demi Moore.

Originally called Valkenvania and clearly made for adults, it was bowdlerised to remove all the gross-out content that would have made it a cult success. The same occurred to the studio’s other headache at the time, The Bonfire of the Vanities, based on Tom Wolfe’s bestselling novel.

Robey describes other examples of filmmakers differing with their financiers about what was fit for public fare. All were ahead of their time.

Tod Browning’s Freaks (1932) was considered scandalous for casting disabled circus people. It has since become a cinema classic. Katharine Hepburn’s cross-dressing in Sylvia Scarlett (1935) turned off audiences. Co-star Cary Grant and director George Cukor survived this setback, but Hepburn’s acceptance by audiences had to wait for nearly a decade.

The best-known example of studios having second thoughts in the 1940s was The Magnificent Ambersons (1942), Orson Welles’s follow-up to Citizen Kane. It was an epic family drama, a staple of today's streaming TV, but ill-timed for America’s entry into World War II.

Orson Welles during the filming of The Magnificent Ambersons.

RKO tested it to an audience of bored teens, later hacking it from 132 minutes to 88. Welles could not complain, as he had fled to Brazil, possibly to avoid war service.

Robey includes only one flop from the 1950s, a golden era for Hollywood. It was an epic set in Ancient Egypt, unknown territory for even an all-rounder such as Howard Hawks. Land of the Pharaohs (1955) briefly employed William Faulkner as a screenwriter, but it lacked major stars or the prestige of Cecil DeMille’s biblical extravaganzas. Martin Scorsese recycled the plot for Casino, even shoving in a sphinx and a pyramid from the Luxor hotel in Las Vegas.

Adaptations that go astray are common among flops. Dr Dolittle (1967) as a musical ended an era of ‘roadshows’ in the 1960s that reached their pinnacle in The Sound of Music. The high-octane French thriller The Wages of Fear (1950) was remade as Sorcerer (1977) by William Friedkin, who was then at his peak with The French Connection and The Exorcist.

His career survived this budget blow-out, as did David Lynch, whose version of Dune (1984) was just as troubled. Other remakes or sequels that make Robey’s list are Speed 2: Cruise Control (1997); Babe: Pig in the City (1998), which cost three times the original; and Rollerball (2002).

The latter was nearly the end of the line for director John McTiernan, who was sentenced to a US Federal prison for perjury and involvement in an illegal wiretapping scandal.

The acclaimed Coen brothers similarly blew their reputation as efficient filmmakers with The Hudsucker Proxy (1994), which spent millions on sets but whose lack of chemistry among the cast earned the description of a “feathered fish”. Paul Newman regretted he had come out of a four-year retirement for his role. The Coens learned their lesson and rebounded with Fargo.

Tim Robbins and Paul Newman in The Hudsucker Proxy. Warner Bros.

That was not the case with Finnish director Renny Harlin, who had just married Geena Davis. She wanted an adventure-packed vehicle and chose Cutthroat Island, a pirate drama. Michael Douglas bailed on learning he would be second-string to a pirate’s daughter. MGM lost US$190m and production company Carolco, which made the Rambo trilogy, went out of business.

Harlin was later associated with A Sound of Thunder (2005), based on a short story by Ray Bradbury. Most of its budget was spent on the shoot, leaving nothing for special effects. Supernova (2000), The Adventure of Pluto Nash (2002), and Catwoman (2004) all sank without a trace, and are hard to find in any online source.

Prodigious producer Joel Silver, with scores of titles to his name, was associated with both The Hudsucker Proxy and Rollerball. His successes included The Matrix series by the Wachowski trans sisters Lana and Lilly, who hit a bump with Speed Racer (2008).

The loss on Cutthroat Island was nearly matched by Pan (2015), Joe Wright’s ill-fated attempt to turn the Peter Pan children’s story into an adult one, which he then had to undo. The estimated loss was US$150m on what Robey says was “nervous unoriginality cloaked by an expensive façade of novelty”. Variety labelled it a turkey “headed for a low-altitude flight”.

‘Art’ movies are seldom rated as flops, because they wear their low budgets with pride. That was not the case with Synecdote, New York (2008), which fell US$15.5m short in covering its costs. It was a disaster for Oscar-winning screenwriter Charlie Kaufman, who was left “bobbing without a raft” from his entanglement with Sony Pictures. He resorted to crowdfunding for the innovative Anamolisa (2015) to restart his career.

Robey's choices are highly personal, chosen on the basis of disastrous production stories and dismal box office returns. That eliminates other well-known "flops" that eventually broke even or have had a second life. None of his profiles is as boring as the movies themselves, which, sadly, are now hard to find.

Box Office Poison: Hollywood’s story in a century of flops, by Tim Robey (Faber).

Nevil Gibson is a former editor-at-large for NBR. He has contributed film and book reviews to various publications.

This is supplied content and not commissioned or paid for by NBR.