Haast’s giant eagle: A journey amid rabbit holes

Peter Walker also looks into Polynesia’s origins, Canterbury’s founding.

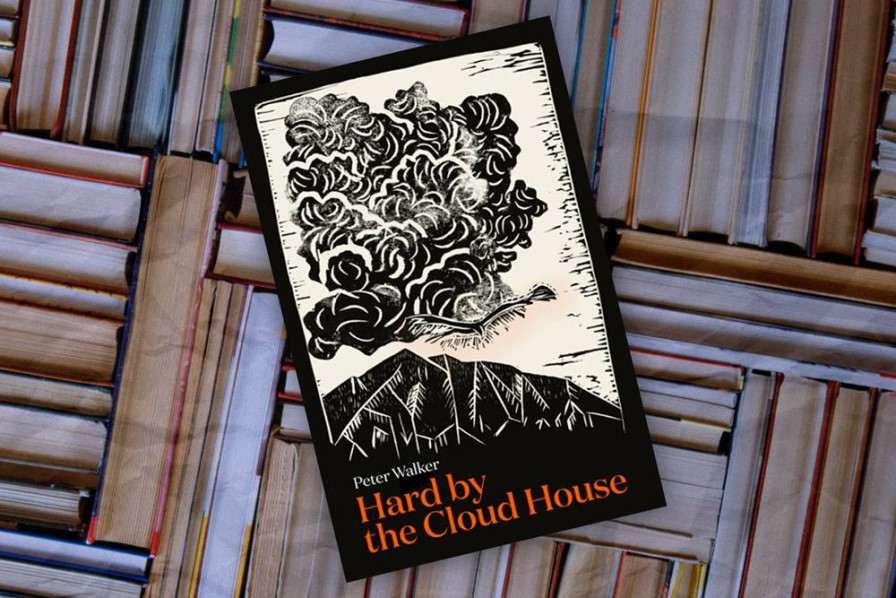

Hard by the Cloud House, by Peter Walker.

Peter Walker also looks into Polynesia’s origins, Canterbury’s founding.

Hard by the Cloud House, by Peter Walker.

Packed houses over three days at the Auckland Writers Festival signalled readers’ desires to get up front and personal with their favourite writers. It’s the same overseas, where similar festivals have become hugely successful, and no doubt equally beneficial to the publishing industry.

The piles of hard-copy books on sale indicated this age-old product was far from dead. However, the changing media scene means this may resemble the sharemarket’s dead-cat bounce.

Festival audiences are overwhelmingly old, having been educated before the digital age, and bourgeois in lifestyle. They need to be as books are an expensive luxury compared with the cheap paperbacks of last century.

Festival sessions, lasting less than an hour, weren’t cheap, either. It cost the price of a book to hear international authors in the flesh. Historian Peter Frankopan, who made at least two appearances, was reluctant to answer the question – what’s next?

He implied the hard work to establish his fame was over, and he name-dropped several countries where he had been in recent weeks. All those festivals and lecture invitations.

Peter Walker.

These are the tip of an iceberg. Only a few books and authors become commercially successful relative to those who want to be. One recently published first novelist emailed me with this observation: “When I was trying to find an agent or publisher in New Zealand for my book, I spoke to one of the leading agents. She said that her agency was now representing only women fiction writers and she had no interest in looking at my book.”

He also mentioned a second-hand story. “One agent, when approached by someone seeking representation, reportedly said that there were more people writing books these days than reading them.”

That emailer was not Peter Walker, who has completed four books since his debut, The Fox Boy (2001), a based-on-fact memoir. He started his writing career at The Dominion in Wellington in 1976, before moving overseas to spend 30 years in London, mainly at The Independent.

He has written two novels, The Courier’s Tale (2010), set in Renaissance Italy and the court of Henry VIII, and Some Here Among Us (2015), about a group of students in Wellington and what happens to them over several time periods.

Walker now lives in the Far North and has just released his latest work, Hard by the Cloud House, which has attracted favourable reviews and several broadcast interviews. It was recommended to me by a close relation, as the topic would not normally attract me.

For a start, the title needs explanation. It is based on the Māori legend that clouds come and go from their home in the sky. Legend plays a large role in a sprawling narrative that crosses millennia in time, mixing fact and supposition.

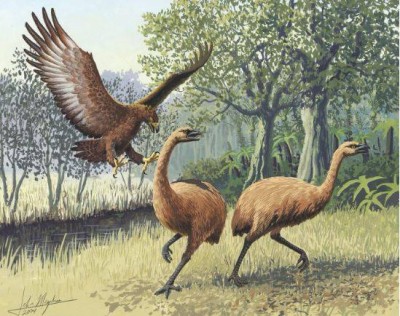

Hunting moa: John Megahan’s illustration (2005).

The inspiration was a newspaper story Walker saw in London 15 years ago about remains found in caves north of Westport that were like the extinct Haast’s eagle, the prehistoric world’s largest winged bird.

Māori legend mentioned the pouākai, a “kind of winged lion, huge in size, approaching the upper limit for flight, the apex predator in a complex ecosystem, swooping down to kill giant herbivores ten times its weight which roamed the forests and grasslands”.

The description references the moa as its main prey. The legend also told how 50 warriors hiding in a lake overwhelmed the pouākai when it attacked from the skies. Such birds, with their wide wingspans, can only exist in mountain areas. Most birds, if they fall into limestone grikes or caves, are unable to fly out vertically and escape.

It is believed the eagle and the moa became extinct in the 15th century after the arrival of early Māori in the previous century. The first archaeological evidence of a large eagle occurred in 1870 when Canterbury Museum director Julius von Haast led an expedition to inspect moa bones on George Moore’s Glenmark estate in the Torlesse Range of the Southern Alps.

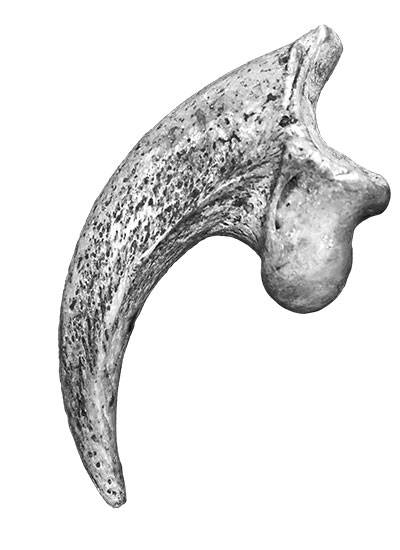

Eagle’s claw found at Glenmark (1871).

The following year, among the bones, the researchers spotted a huge claw that stood out “like a dagger at a pyjama party”. Unfortunately, other remains were lost and the discovery was largely forgotten, except for Moore being credited with the eagle species being known as Harpagornis moorei.

The story jumps to 1980, when cavers in the extensive network at Honeycomb Hill near Karamea found a wing bone that differed from the others. A CAT scan showed it was related to small eagles from Papua New Guinea and Australia. They had presumably been blown across the Tasman Sea.

Walker makes his own expeditions to Honeycomb Hill and the Torlesse Range, raising the possibility that the giant eagle had evolved over millennia before the arrival of the first Māori. These chapters include some hard-case characters, who bring the book alive.

At this stage, Walker indulges in more sidetracks, which might be better called rabbit holes. One of them is the contentious business of how Ngai Tahu lost control of the South Island. They were vastly outnumbered by European settlers from the 1850s and had no means of resistance.

Some welcomed the prospect of newcomers as protectors against raiding tribes from the north. Among many colonial villains, Moore is pilloried as pitiless toward swagmen. This is a repeat exercise from The Fox Boy, which examined the impact of colonisation in Taranaki.

The next rabbit hole is linking the legendary pouāki (Hōkioi for northern Māori) – a symbol of power, danger and the sublime – to the mythical stories of predatory birds in the Middle East and Asia. Walker is influenced by a professor of Iranian studies, David Bivar, who lists raptors such as the Griffin, Anqa, Rukh (or Roc), and Simurgh. These resided near the then edge of the known world – the ‘Great Encircling Ocean’ that surrounded Asia, Africa and Europe.

A complicating issue is the Korotangi, a pigeon-sized carved stone bird of Asian origin that is a Tainui taonga. It was discovered in 1878 near Aotea Harbour, the landing place of the Tainui ancestral waka, between Kāwhia and Raglan.

Korotangi, Tainui’s sacred stone bird from Indonesia.

Its journey from the Polynesian homeland, Hawaiki, is another Māori legend. Latest research showed the carving was probably made from Indonesian serpentine around 790. How it came into the possession of voyaging Polynesians who had no metal tools remains unknown. It was returned to Tainui in their treaty claim.

In Persian and Chinese legend, giant birds had been swept eastward and southward to parts where no humans had gone until the Polynesian voyagers. The South Island was the last and remotest land mass to be inhabited.

These voyagers had told of visiting places where “no one answered”. This produces yet another sidetrack as Walker, on a junket as a travel journalist to French Polynesia, invites the artist Jim Viviaere to accompany him as his photographer.

Viviaere, who had been raised in Hawke’s Bay by adoptive parents, had no interest in cameras but he was interested in his Cook Islands ancestry and the location of Hawaiki.

This serendipitous journey ends at a place called Taputapuatea, a sacrificial marae in Raiatea from which the Polynesians set off to the Cook Islands. It was the only place where Viviaere, who died in 2011, agreed to be photographed.

It is unfortunate Walker’s publishers cram his small uncaptioned illustrations into the text pages rather than splash out on a glossy paper insert, which is common in a $40 paperback.

Walker provides 128 source notes and acknowledges the help of several dozen experts. But there is no index or bibliography, which limits its value as a work of scholarship from a reputable university publisher. It’s likely Walker, whose main career was journalism, wants to entertain as well as inform his readers, rabbit holes included.

Hard by the Cloud House, by Peter Walker (Massey University Press).

Nevil Gibson is a former editor at large for NBR. He has contributed film and book reviews to various publications.

This is supplied content and not paid for by NBR.

Sign up to get the latest stories and insights delivered to your inbox – free, every day.