Good works from bad actions

ANALYSIS: A history of prison labour in New Zealand and the Pacific Islands.

WATCH: NBR columnist Nevil Gibson speaks with Calida Stuart-Menteath.

ANALYSIS: A history of prison labour in New Zealand and the Pacific Islands.

WATCH: NBR columnist Nevil Gibson speaks with Calida Stuart-Menteath.

One of the pleasures of reading history is that no two writers will tell the same story.

The post-modernist approach that brands Western civilisation as oppressive and exploitative has prompted a strong response from those who are more nuanced in the pros and cons of imperialism and colonialism.

Jared Davidson.

Historical accounts taking a ‘top down’ approach that focuses on wars among major powers and the rise and fall of rulers are balanced by ‘bottom up’ historians who study the labouring classes and the lives of ordinary people.

The use of prison labour is a topic that lends itself to both schools. In the Victorian era, which coincided with the expansion of empires to countries far beyond Europe, punishment through labour gave criminals an opportunity to reform through acquisition of skills, deterred others from committing crimes, and reduced the costs of imprisonment.

Among the side effects of Britain’s Industrial Revolution – which resulted in new-found wealth for the middle and skilled working classes – were poverty, crime, and fears of over-population. One solution was to transport prisoners from Britain and France to Australia, New Caledonia, and other colonies where they became a source of labour.

While New Zealand never became a penal colony, the use of prison labour was integral to the early stages of settlement. It was also used in the Pacific Islands during New Zealand’s period as an imperial power.

Blood & Dirt, by historian Jared Davidson, recounts its first use by missionaries at the beginning of the 19th century as the penal colony of New South Wales looked eastward to New Zealand. Davidson has previously appeared in this column with his story of a workers’ uprising in colonial Nelson.

When Samuel Marsden arrived from Sydney at Hohi in the Bay of Islands on December 22, 1814, the ship Active contained a crew of Irish and other convicts who set about building houses.

The venture didn’t last long and most went back across the Tasman. But it started a tradition that was critical to the colony’s early development. Crimes in those days ranged from public disorder and drunkenness to assaults and murders.

But most of those who saw in the inside of gaols were seamen who had illegally jumped ship, hoping for a better life on land.

Prisons were built in the centre of the coastal settlements and chain gangs were common sights up to the 1870s as they hammered rocks into gravel for roads and streets.

Building Rocks Rd, Nelson, 1894. Photo: Tyree Studio Collection, Nelson Provincial Museum.

Quarrying and brickmaking were staple activities for prison labour, as were public buildings, seawalls, and breakwaters that benefited the citizens of Auckland, New Plymouth, Whanganui, Napier, Wellington, Nelson, Lyttelton, and Dunedin, where prisoners stayed on hulks that followed the gangs building the perimeter of Otago Harbour.

Lyttelton put more of its population in jail per head than anywhere else. In 1872, it had a daily muster of 53 labourers.

Social attitudes changed in the 1870s, banishing prisons from the sight of law-abiding citizens. Although labour was always short in colonial life, rising unemployment among the paid workforce reduced the use of gangs because they were “taking jobs from ‘honest, industrious’ men”.

Fort Ballance, Miramar, 1880. Photo: Alexander Turnbull Library.

Invasion fears from the ‘Russia scare’ in the late 19th century triggered a boom in coastal fortifications. Prisoners helped build facilities and gun emplacements at North Head and Fort Cautley (Takapuna-Devonport) in Auckland, Fort Ballance (Miramar) and Point Halswell in Wellington, Lyttelton, and Taiaroa Head in Otago.

Writer and politician John A Lee was a prison worker on North Head after being jailed for drunkenness and other minor offences in 1912.

By the 1890s, attention turned to using prison labour in remote places that needed development. A foray into building a settlement at Milford Sound in 1890 proved disastrous due to bad weather and poor working conditions.

Greater success came when the Prison Service turned to planation forestry to counter a feared wood shortage from widespread tree felling. The barren treeless plains around Rotorua and the Central Plateau were planted at Galatea as early as 1869.

This region later became one of the world’s largest tree plantations. Tree planting was also extensive at Hanmer in north Canterbury and Dumgree, near Seddon, in Marlborough. Dumgree was a flop, with half of the trees dying in a drought and unhappy prisoners sabotaging their tools and plants.

By contrast, the move to Hanmer was a great success, starting with some 60 prison planters in 1903. Eventually, forests covering an area of 1500 acres were planted with 4.5 million trees that created a “crazy quilt” of dozens of different varieties at different times.

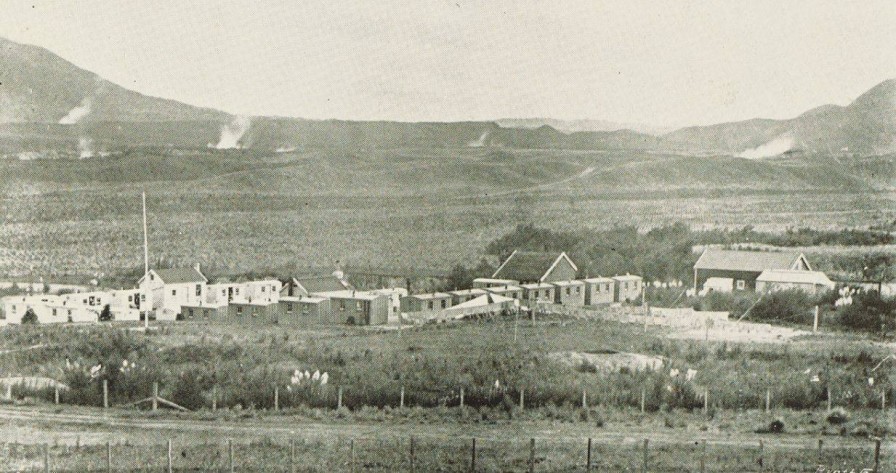

Waiotapu Prison, 1906. Photo: Auckland Libraries Heritage Collection.

In 1913, the forestry prisons at Hanmer and Waiotapu in the North Island were closed and replaced by paid labour. Prisoners working outdoors posed few security risks, but opposition to them being exploited as cheap labour became a concern. Idleness and low efficiency were other worries.

As involvement in forestry declined, the Prison Service turned to farming, helping to usher in an era of greatly increased agricultural production from the 1920s. By 1923, 70% of prison workers were employed in farming. Dairying, horticulture, and even tobacco growing was conducted on a commercial scale that exceeded most private farms.

Māori land seizures in the central North Island resulted in prison farms at Tokanui and Waikeria, followed in the 1930s by Hautū and Rangipō. The Prison Service produced annual revenue from its farms as high as £83,806 ($7.4m in today’s money). The farms also became the model for larger make-work schemes for the unemployed during the Depression.

Elsewhere, prison farms and other developmental activities such as construction, drainage, quarrying, and brickmaking occurred at Wi Tako (Trentham), Paparua (Christchurch), and Invercargill. Many forms of agricultural innovation were introduced, including the use of aerial topdressing. Paparua became famous for its output of potatoes and lucerne from formerly arid shinglelands.

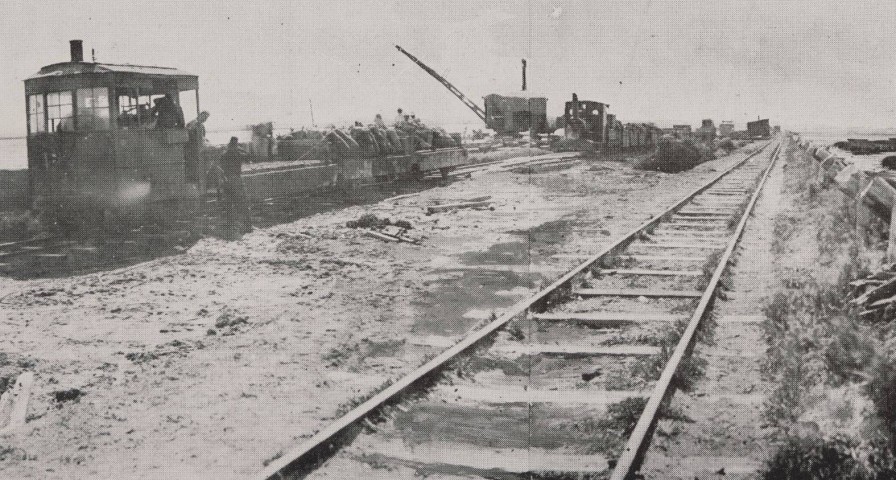

Invercargill estuary reclamation, 1912. Photo: Alexander Turnbull Library.

Further south, one of the country’s biggest drainage projects, the New River estuary at Waihopai adjacent to Invercargill, reclaimed some 10 square kilometres of land. Prisoners erected workshops, built a railway line, and used diggers and cranes to build embankments.

A borstal farm on the reclaimed land was later valued at £60,000 to £70,000 (or $4m) and in 1944, other parts were used for an airport. Environmentalists have criticised the ecological damage from this form of drainage but its contribution to the Southland’s prosperity is unquestioned.

Davidson highlights the lack of acknowledgement in official records of the major achievements he describes in extensive detail. He notes a 1975 glossy publication on the conversion of the Central Plateau’s pumice lands into productive pastoral farms ignores the role of prison farms.

The ‘bottom up’ view of history dictates the integral role of labour – whether captive or free – as being exploited in the capitalist system. “Capitalism has done a tremendous job of portraying itself as natural and entirely normal,” Davidson writes, observing that society took the same view of prisons and therefore their contribution for granted.

He has corrected the record in an outstanding way by producing a book of which he and his publisher can be proud. It has an illustrated hard cover, 70 pages of notes, sources and index, with hundreds of illustrations spread throughout the small-type text. Davidson has put his day job as research librarian manuscripts at the Alexander Turnbull Library to excellent use.

Blood & Dirt: Prison labour and the making of New Zealand, by Jared Davidson (Bridget Williams Books).

Nevil Gibson is a former editor at large for NBR. He has contributed film and book reviews to various publications.

This is supplied content and not commissioned or paid for by NBR.