Good as gold: How Chinese business came to New Zealand

ANALYSIS: A history of change from goldmining, laundries, and market gardening.

Golden Enterprise: New Zealand Chinese Merchants 1860s-1970s and Bold Types.

ANALYSIS: A history of change from goldmining, laundries, and market gardening.

Golden Enterprise: New Zealand Chinese Merchants 1860s-1970s and Bold Types.

At the height of New Zealand’s most ‘progressive’ phase in the late 19th century, populist premier Sir Robert Seddon and arch-reformer William Pember Reeves had one exception for who qualified for ‘God’s Own Country’.

Chinese immigrant labourers, who first arrived in 1866, were not welcome in the “white working men’s paradise”. Reeves tried to ban them in the Undesirable Immigrants Exclusion Bill in 1894, but this only became law in 1919 to exclude Germans, Austrians, and Marxists.

His landmark colonial history, The Long White Cloud – Ao Tea Roa (1898), described a population of 785,000 “whites, browns and yellows”. The “yellows” were some 3500 Chinese, who were described as a “true alien element”.

He continued: “They do not marry – 78 Europe and 14 Chinese wives are all they have … They are not met in social intercourse or industrial partnership by any class of colonists, but work apart as gold-diggers, market-gardeners, and small shop-keepers, and are the same inscrutable, industrious, insanitary race of gamblers and opium-smokers in New Zealand as elsewhere … Despised, disliked, dwindling, the Chinese are bound soon to disappear from the colony.”

Revisionist historians have turned this once commonly held view on its head. It’s now the “white working men” who are “despised, etc” for the legacy of colonialism. The National Library recently prompted historian Paul Moon to cancel a forthcoming lecture because it wanted to censor publicity material relating to colonialism.

Phoebe Li.

The role of Chinese in New Zealand history is not an obscure backwater. It has been widely studied and, in 2002, led to an official government apology for the poll tax that applied until 1934. In compensation, the Chinese Poll Tax Heritage Trust was established.

That trust’s investment in Golden Enterprise: New Zealand Chinese Merchants 1860s-1970s, by Dr Phoebe H Li, is well spent; this coffee-table book of more than 200 pages has dozens of historic photos and is rich in scholarly material for the general and specialist reader.

While focused on a narrow merchant class, it takes a broader view that encompasses New Zealanders’ interest in Chinese culture and history, the survival of a marginal community in a colonial economy, the impact of strict immigration laws, the effect of assimilationist policies, and the adaptation of Chinese entrepreneurial activity to changing conditions.

Li also describes how events in China during the 20th century changed the relationship with New Zealand, and tensions this created within a community that originated from a small geographic area of southern China and that, from the 1990s, had to accommodate immigrants from all parts of China as well as a diaspora from Hong Kong and elsewhere in Asia.

Her perspective differs from earlier studies, which are the work of New Zealand-born Chinese. She comes from Shenyang, capital of Liaoning province in northeastern China, and left during Deng Xiaoping’s opening up polices of the late 1990s to study at tertiary level in Australia and New Zealand.

Unable to find an academic post in Chinese studies after completing a PhD on Chinese immigration to New Zealand, she returned to China and travelled extensively over 2013 to 2019. Back in New Zealand, she was involved in pictorial exhibitions of Chinese emigration and the commissioning of this book.

Auckland’s ‘Chinatown’ in Greys Avenue, 1940s. Source: Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections Footprints 02487, photographer Alton Francis.

The first generation of immigrant merchants ran ‘gold mountain’ businesses that started with fur sealers in the early 1800s and flourished with the gold rushes in California and Australia. The first Chinese miners arrived in Otago in 1861 from Victoria, and later spread to the West Coast.

They had demands for food and laundry services, as well as the means to remit money back to their families in China and promote further migration. By the 1930s, Chinese ran 600 market gardens, 200 laundries, and 200 produce shops.

It wasn’t much different from two decades earlier when the Chinese consul noted New Zealand had “among the most infertile lands in the world” and the “poorest and most ignorant of all the overseas Chinese”.

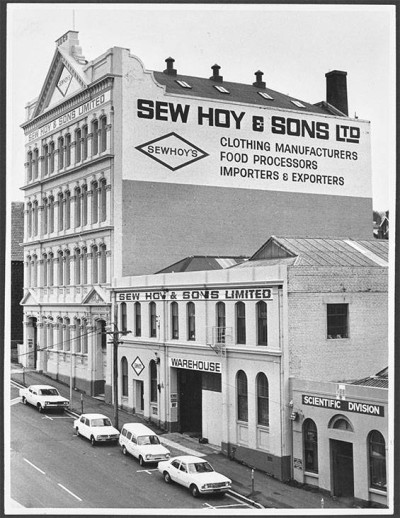

Choie Sew Hoy opened his first shop in Dunedin in 1869. Over several generations, the Sew Hoy name was synonymous with business. It peaked in 1958 as an employer of 700 mainly non-Chinese in textile and clothing but collapsed in 1989 when that industry lost protection.

Sew Hoy buildings, Dunedin. Source: Hocken Collections.

Sew Hoy also made noodles for the local market as well as exporting fungi and deer velvet, as did the Wong Doo family in Auckland. The triumph of Mao’s communists in 1949 wiped out New Zealand-owned businesses and properties in China, while restoring the role of colonial Hong Kong up to the Japanese occupation.

Republican China, which had emerged after the revolution in 1911, supported the Allied cause in both world wars. Local Chinese also supported these war efforts, mainly in food production, but had divided loyalties up to the end of the civil war.

The Cold War ended remittance links with China, resulting in greater property investment within New Zealand. Another outcome was the lifting of immigration restrictions, putting Chinese family unification on the same basis as all other nationalities.

Naturalisation of Chinese in New Zealand accelerated as ties with China lessened, until recognition of the People’s Republic in 1972, setting off a new era in trade. The Yee family’s South Seas Trading in Christchurch, and James Luey’s Ocean Commodities in Wellington, initially prospered with a range of imported goods. Laundries disappeared with the spread of home appliances.

Meanwhile, the few remnants of a ‘Chinatown’ in the main centres disappeared in the 1960s along with the traditional laundries and produce and variety shops, typified by Wah Lee’s in Auckland. Generations of assimilated and educated Chinese Kiwis became young professionals, while the family businesses joined the mainstream.

The Ah Chee family’s involvement in the Foodtown chain and Peter Chan’s Tai Ping supermarkets were indicative of changes that arose from the liberalised economy and the game-changing Immigration Act of 1987, which allowed foreign-born Chinese to outnumber their New Zealand-born equivalents by three to one in every census since 2006.

Barry Wah Lee and his wife in their Hobson St shop, Auckland, in 2016. It was in Greys Ave from 1904-66. Photo: King Tong Ho.

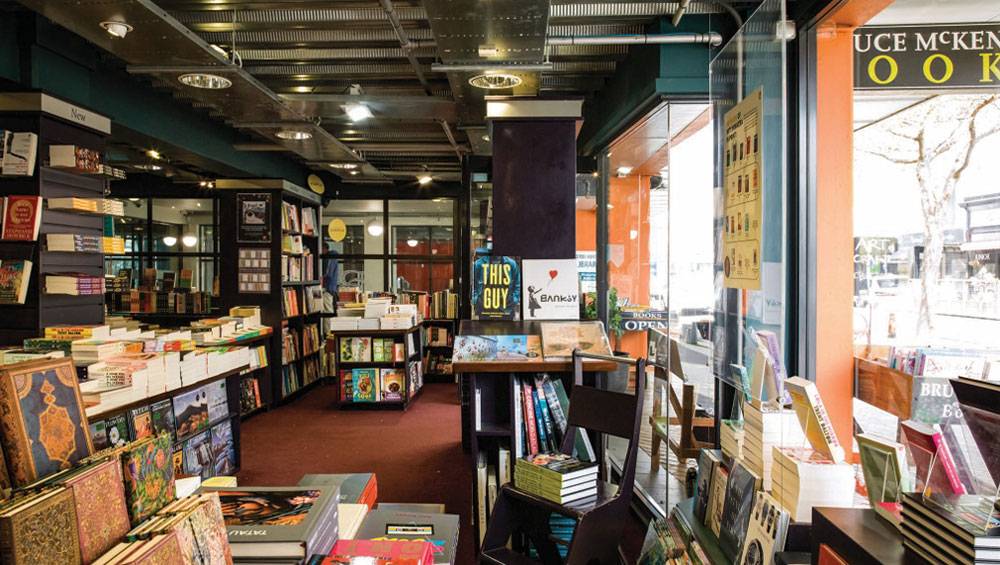

Just as traditional Chinese businesses were disappearing, so too have those associated with the print media. Bold Types, by Jane Ussher, Jemma Moreira, and Deborah Coddington, is a lavish showcase of 32 independent and decidedly uncorporate bookshops.

Coddington, a former publishing rep and bookseller in Martinborough after a career in journalism and a term in Parliament, chose and visited them all with Ussher, whose photographs are the main attraction. Moreira edited the owners’ descriptions of their shops’ distinctive features and customers.

Readers can be assured the country’s handful of leading main-centre bookshops are profiled – Unity in Auckland and Wellington, UBS in Christchurch and Dunedin, and Scorpio, also in Christchurch. Second-hand dealers and collector outlets were ineligible for inclusion. (Inevitably, they have had a book on their own.)

Bruce McKenzie Books in Palmerston North. Photo: Jane Ussher.

It’s good to know small towns such as Matakana, Thames, Havelock North, Ōtaki, Twizel (since closed), and Wānaka can support a quality bookshop. Discerning readers in the large-city suburbs of Remuera, Grey Lynn, Parnell, Mt Eden, Herne Bay, Devonport, Milford, Te Aro, Karori, and Petone are also well catered for.

The pickings in secondary provincial centres are thinner – Gisborne, Napier, Whanganui, Palmerston North, Masterton/Wairarapa, and Nelson all have long-established booksellers or newcomers worthy of inclusion. Whangārei, Hamilton, Tauranga, Rotorua, New Plymouth, Blenheim, Timaru, and Invercargill do not.

Personally, I have been to most of them, for the same reasons as the owners provide. Some I wouldn’t bother with, as they cater for tastes other than mine, or are too small and intimidating for a brief browse.

This addition to the coffee table is not intended as a definitive catalogue or guide. But it’s a memorable tribute to those who sacrifice above-average incomes for the satisfaction of serving grateful customers.

Golden Enterprise: New Zealand Chinese Merchants 1860s-1970s, by Phoebe H Li (Chinese Poll Tax Heritage Trust).

Bold Types, by Jane Ussher, Jemma Moreira and Deborah Coddington (Ugly Hill Press).

Nevil Gibson is a former editor-at-large for NBR. He has contributed film and book reviews to various publications.

This is supplied content and not commissioned or paid for by NBR.

Sign up to get the latest stories and insights delivered to your inbox – free, every day.