Frontier women: Triumphs and tribulations of pioneer farming

How the Victorian era created one of the world’s most admired societies.

WATCH: NBR columnist Nevil Gibson speaks with Calida Stuart-Menteath.

How the Victorian era created one of the world’s most admired societies.

WATCH: NBR columnist Nevil Gibson speaks with Calida Stuart-Menteath.

In the two decades between 1871 and 1891, the growth in the non-Māori female population of colonial New Zealand dramatically reduced an imbalance of the sexes.

It was dramatic on several counts. The flow of immigrants mainly from Great Britain was the single longest migration in human history. It required a sea voyage lasting three to five months in a confined space and virtually no stops before the completion of the Suez Canal in 1869. For most, it was a one-way trip to a place they knew little about.

In 1871, the males aged over 20 numbered 89,000, well ahead of females at 46,000, or 34%. In a couple of decades, the proportion of women jumped to 44%, mainly due to well targeted recruitment of single women from Britain’s rural areas.

For these women, the second half of the 19th century involved declining wages and increasingly harsh employment conditions. Compared with those who flocked to the factories of industrialised England, the rural dwellers occupied the lowest rungs of society.

For single women, the work options were either the mills or domestic service. By comparison, New Zealand offered the prospect of higher wages for service workers.

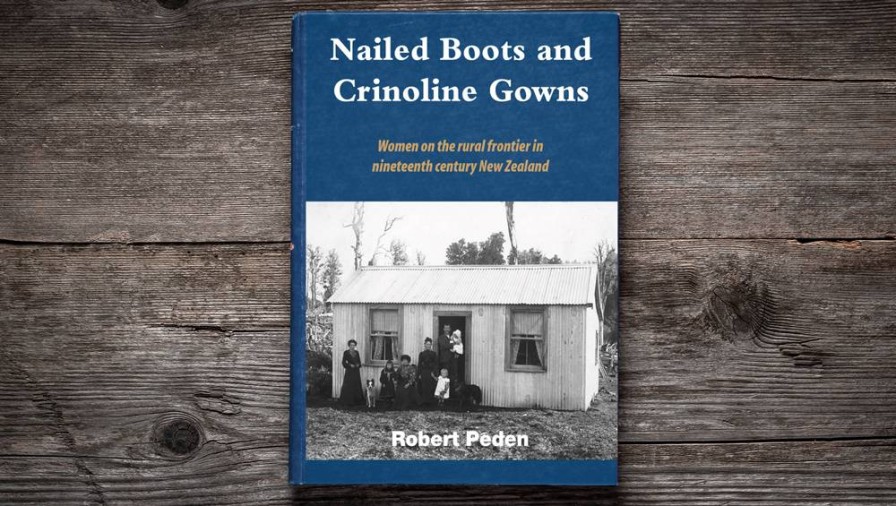

Robert Peden.

“[T]he high demand gave them the power to decide who they worked for, how they went about their work and where they worked,” writes Robert Peden in Nailed Boots and Crinoline Gowns, a history of rural women in 19th century New Zealand.

However, the rural sector was not the first choice for these young women. They were highly mobile and marriage was an appealing option if husbands had good economic prospects.

Another major difference from Britain was the lack of rural communities. Villages in the English sense did not exist, and there was no history of generations owning or leasing the land. Remoteness and isolation were defining characteristics of the earliest New Zealand farms and stations.

Peden spent more than 20 years working in South Island high country stations as a shepherd and farm manager. He returned to university in 1999 to study for a masters degree and then a PhD respectively at Canterbury and Otago universities. This experience informs his work, which includes a history of Mt Peel Station in South Canterbury.

Peden’s archival research of diaries, correspondence, and other primary sources demonstrates an academic discipline that provides context to coloured accounts of the time, as well as generalisations that the lives of pioneer rural women were ones of unstinting domestic drudgery and “eternal pregnancy”, as James Belich described it in Paradise Reforged (2001).

Admittedly, primary sources such as diaries or journals were mainly written by educated middle and upper class women. But they provide detailed accounts of daily life on farms, including those of servants and labourers.

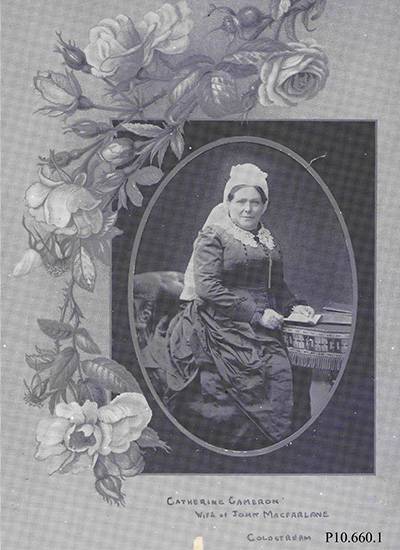

Catherine Macfarlane.

These form the basis of chapters on the rituals of courtship and marriage, childbirth, and the raising of families, as well as dealing with health, education, and morality (religion). Often it required management of financial affairs, particularly when a husband died earlier than usual.

The first Europeans to arrive in New Zealand were American whalers, who established themselves in coastal communities in Southland and Otago. They integrated with local Māori, who provided wives as well as sailors. Couples established the first permanent settlements.

Christian missionaries were not far behind and comprised the first married immigrant couples. Peden makes good use of Catherine Macfarlane’s diaries to trace the life of a pioneer woman who was eventually one of the largest landowners in North Canterbury.

She arrived in 1840 as the 14-year-old daughter of Donald Cameron, a Gaelic-speaking Scottish weaver who had been hired by the New Zealand Company for its settlement at Wellington. At 22, Catherine married John Macfarlane, another Gaelic speaker who had land in the Wairarapa.

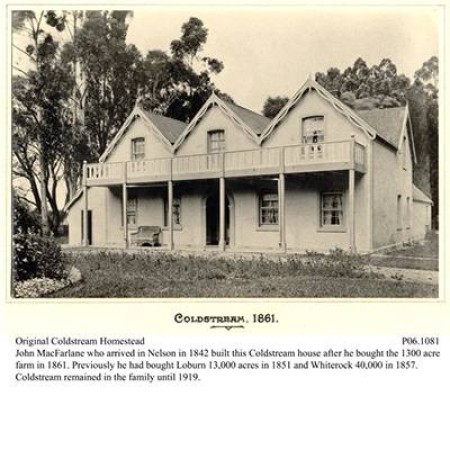

The Macfarlanes’ Coldstream residence in 1861.

In 1850, due to tensions over land ownership, they headed for Canterbury where they established farms at Loburn and Coldstream, near Rangiora. These were isolated places in the 1850s. For two years, Catherine never saw another Pākeha woman. By 1880, a few years before John’s death, the Macfarlanes were among the region’s wealthiest.

Catherine took over the business and lived for another 24 years until her death in 1908. She was typical of many other rural women in having 11 children in just 14 years.

During the 1870s and 1880s, New Zealand Pākeha women had one of the highest birth rates in the world. The average family had seven or eight children. One, Emily Monk, had her first at 16 and nine more, living to 97 and dying in 1955.

Survival rates were also among the highest in the world, attributed to improved nutrition (lots of protein), reduced spread of infection (due to the sparse population) and a high level of sanitation (a habit learned from migrants ships that were cleaned daily).

Fertility rates dropped sharply after 1890 as women delayed marriage until their mid-20s. Compulsory education for both sexes from seven to 13 years was mandated in the 1877 Education Act. This mainly benefitted the urban population. In remote farming areas, access to education was harder.

In these cases, education became yet another responsibility for rural wives, who also ensured the teaching of the Victorian era’s dominant Christian values. Sundays were strictly observed as days when the solid workload of the week was eased.

Those domestic duties, Peden describes, involved days devoted to washing, ironing, cooking, cleaning, sewing, and (in season) preserving fruit and vegetables. Washing before the days of indoor laundries and machines was the heaviest duty for many wives, whose husbands worked on remote farms, or were tree fellers and road builders.

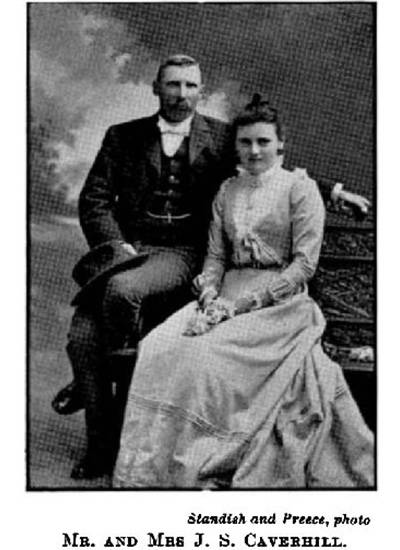

John and Frances Caverhill on their wedding day in 1855.

The task required boiling hot water outdoors, hand scrubbing boards with homemade soap, followed by mangling, drying, and ironing. Healthcare was also complicated by remote living. Peden describes the many ailments and risks faced by families without easy access to medical facilities.

Frances Caverhill’s diaries are a valuable source of complaints about headaches, body pains, rheumatism, and boils, which were treated with a variety of laxatives, castor oil, and patented medications.

Frances King married John Caverhill in 1855 after a romance that demonstrated few marriages in colonial New Zealand were made for dynastic purposes. John was a “pre-Adamite” – a settler in Canterbury ahead of the original Four Ships in December 1850 – and was highly entrepreneurial but also impulsive.

The Caverhills prospered at their Motunau and Cheviot properties in North Canterbury but lost their fortune after John decided to sell up in 1873 and move to Hawera in Taranaki. Frances’s diary is full of treatments using poultices and plasters, as well as visits to thermal pools and the benefits of cold baths and swimming in the sea.

The Caverhills’ Highfield Station in North Canterbury.

Caverhill’s diary is not the litany of “eternal drudgery and pregnancy” that Belich described. She read every night and names the books she enjoyed. Outside the home, she describes the annual rounds of balls, picnics, pastoral shows, fetes, harvest festivals, and sports days.

Catherine Fulton.

Housebound activities such as needlework, music, and games were high on list of many Victorian households, who enjoyed dressing up; hence the reference to crinoline gowns in the title.

The diaries of Catherine Fulton illustrate another fully engaged life of community service. She arrived in New Zealand aged 19 in 1849 with her parents, William and Caroline Valpy, who were wealthy from his years as a judge in India. Also on the immigrant ship was James Fulton, who also was wealthy enough to buy land.

Within a couple of years, they married and lived on their Ravenscliffe property at West Taieri, south of Dunedin. They had eight children between 1853 and 1866, with many misfortunes, including the death of two sons later in their marriage.

James became a resident magistrate and was elected to Parliament. Meanwhile, Catherine was active for three decades in Christian temperance work for the Salvation Army and the Blue Ribbon Army, as well as women’s suffrage (achieved in 1893) and overseas missions. She died in in 1919, aged 90.

The Fulton’s homstead at Ravensliffe in the early 1900s.

Her life was just one of many women, Peden concludes, who within the bounds of conventional Victorian society “broke through the legal and social constraints placed upon them”.

His book, while heavily dependent on a dozen or so diaries, is backed up by six pages of bibliography, and and index of 17 columns for names and places. Their descendants will find this a valuable guide to balance the revisionist school that belittles the role of those who to build a better place than they had at “home” had to start from scratch in a country that had no resemblance to a civilisation that had evolved over thousands of years.

Nailed Boots and Crinoline Gowns: Women on the rural frontier in nineteenth century New Zealand, by Robert Peden (Fraser Books).

Nevil Gibson is a former editor at large for NBR. He has contributed film and book reviews to various publications.

This is supplied content and not paid for by NBR.

Sign up to get the latest stories and insights delivered to your inbox – free, every day.