From golden years to threatening clouds

Ian F Grant continues his history of New Zealand newspapers.

Ian F Grant continues his history of New Zealand newspapers.

If history provides lessons, then newspapers and the media industry in general could benefit immeasurably. Its lobbyists are seeking government assistance in recovering lost revenue to the internet’s major platforms. Media companies are also unlikely to welcome an end to publicly funded journalism for court and local government coverage.

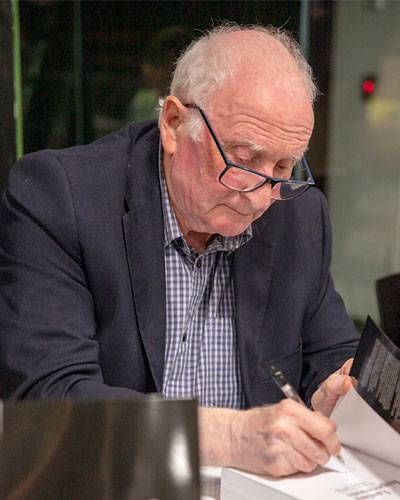

Media historian and publisher Ian F Grant describes the industry’s response to market stresses as a “circling of the wagons” mentality. He has just published the second part of his history of New Zealand newspapers.

The first, Lasting Impressions (2018), covered 1840 to 1920. The second, Pressing On, carries the story to 2000. Grant says his research threw up too much material to fit in the 21st century. This volume runs to 670 pages and would not have been possible without the assistance of the Alexander Turnbull Library, where Grant was an adjunct scholar, and the National Library’s Papers Past, an online repository of eligible newspapers. (Grant, incidentally, was made an Officer of the NZ Order of Merit in this year’s King’s Birthday Honours for his contribution to “literature and historical preservation”.)

Author and publisher Ian F Grant.

Pressing On follows the format of its predecessor: the 80 years are broken into three periods: 1921-45 (“turbulent decades”), 1946-65 (“the golden years”), and 1966-2000 (“gathering clouds”). Newspaper types – metropolitan, provincial, weeklies, and specialist – are profiled on a geographic basis. Context comes from chapters on political, economic, and social events, supplemented by profiles and sidebar stories on censorship and first-person observations.

The emphasis is on what happened, based on sources of the time, rather than an analytical review of the past. This means some controversies are limited by what participants thought at the time, rather than reflective perceptions. Readers who lived through these times, as I did, may find it galling that this lack of retrospection often gives a one-sided view. That is a task for another historian.

Grant provides plenty of material to work on, as each publication’s story contains details on circulation, advertising revenue, printing machinery, pagination, delivery, and other basics of newspaper publishing. This gives a more rounded history than just a focus on editorial activity and personnel.

The broader sweep of newspapers’ role in New Zealand’s development is another strength. The 1920s and 1930s were times of economic turbulence as the brief prosperity after World War 1 led into the Depression and the election of a reformist Labour Government in 1935.

Like other widely spread industries such as brewing, the plethora of newspapers – all metropolitan and most provincial centres had one or more in both the morning and afternoon – was reduced as owners saw benefits in mergers and monopolies.

In Christchurch, debilitating competition between multiple morning and evening titles owned by three companies was resolved by a merger and closures, leaving just The Press and the Christchurch Star-Sun. This was the pattern elsewhere, with Wellington’s The Dominion taking over and closing its morning rival, the NZ Times, in 1927. Competition briefly returned to the capital when the labour movement-backed Southern Cross was launched in 1946. It pioneered front-page news and contained a popular racing form guide but lasted only until 1951.

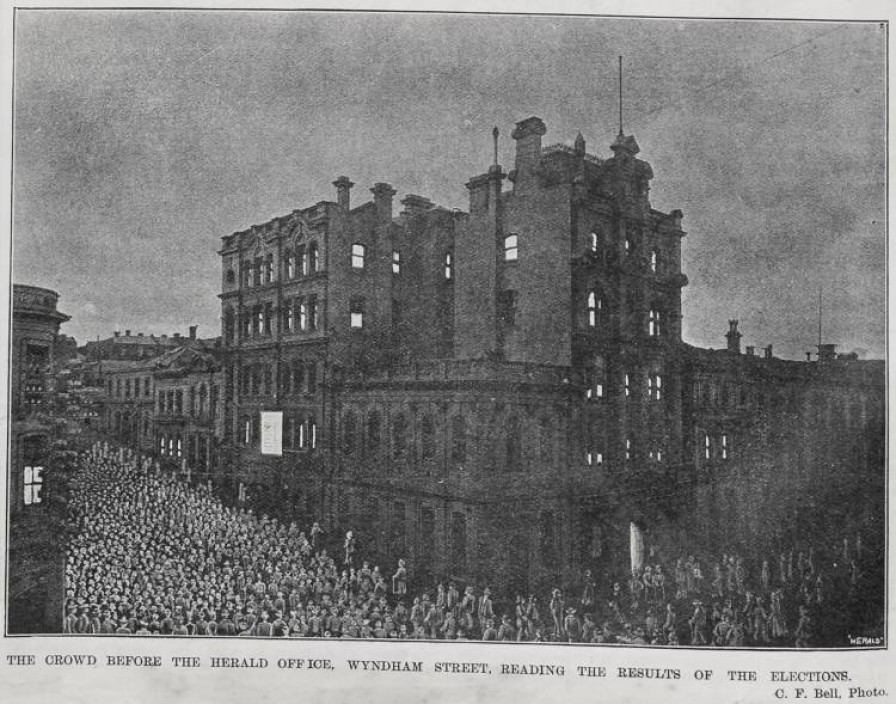

Before TV, election results were posted outside newspaper offices. Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections AWNS-18991215-04-04

At the mid-century, the country had 50 daily newspapers, compared with nearly three times that many in 1921. Most of the closures were in the South Island, where the population fell from parity with the North Island in 1900 to half in 1945. Outside the four metropolitan centres, two-paper towns after 1945 included Palmerston North, New Plymouth, Whanganui, Invercargill, and Greymouth, where the longstanding pro-Labour daily, the Grey River Argus, survived until 1966.

Invercargill’s Southland News closed in 1968. In New Plymouth, the Taranaki Herald and Taranaki Daily News merged in 1962, with the Herald being sacrificed in 1989, a year after the operation was bought by INL, the Wellington-based owner of The Dominion and the Evening Post.

The seller was NZ News, a company controlled by Brierley Investments. The owner of the Auckland and Christchurch Stars was being broken up after gambling and losing on the Sun, a short-lived morning tabloid that failed to shake the New Zealand Herald’s dominance.

Palmerston North lost the morning Manawatu Daily Times to a takeover by the Dominion in 1963, while Whanganui retained competing dailies until 1971 when they merged under Rotorua-based United Publishing and Printing. The Wanganui Herald closed in 1986, leaving the Chronicle as the only daily after NZ Herald publisher Wilson & Horton bought UPP a year earlier.

In Hawke’s Bay, Napier’s Daily Telegraph and the Herald-Tribune in Hastings had merged in 1982 but ran both titles separately. Wilson & Horton again took control after the breakup of NZ News in 1988, later launching a single title, Hawke’s Bay Today, in 1999.

Greymouth was home to the Grey River Argus (1919-66), the only pro-Labour daily.

The tally of closures reached 34 in 2000, including metropolitan dailies in Auckland, Christchurch, and Dunedin. All were evening papers, which were hardest hit by the impact of TV, the loss of advertisers, and changed reading habits. Only the Evening Post survived into the next millennium, though it eventually moved to morning publication in a merger with The Dominion.

Meanwhile, the concentration of the country’s dailies into a duopoly continued, except for Dunedin’s Allied Press. Grant quotes many sources on the conformity of newspapers in content, style, and management. Up to the 1960s, editorial opinion was universally expressed in support of private enterprise and conservative values, though some editors were allowed to be more liberal than others.

Grant cites only one case of an editor being sacked for unacceptable opinions. In his two years at the Ashburton Guardian in the mid-1980s, Rhys Mathias was highly critical of local politicians and civic entities such as the licensing trust. But he went too far in advocating gay rights and announcing he would not report the Cavaliers’ rugby tour of South Africa.

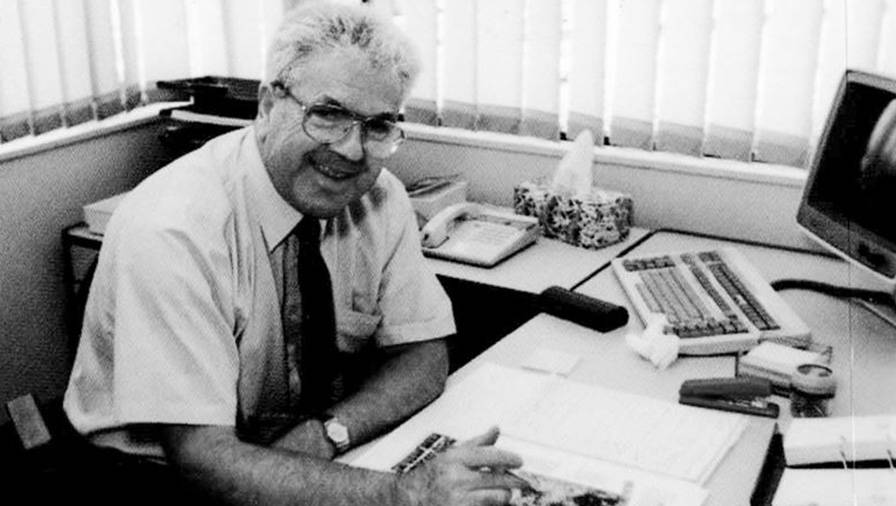

As editor of the Christchurch Star, Michael Forbes ran a ‘dump Muldoon’ campaign.

Michael Forbes was another editor who pushed the boundaries at the Christchurch Star. He denounced the appointment of Sir Keith Holyoake as Governor-General in 1977 and ran a “Dump Muldoon” campaign that upset chiefs at NZ News. They unsuccessfully tried to sack him but eventually he was eased out of his Christchurch job for several posts in Auckland.

The Star was sold to Wilson & Horton, but Forbes stayed on at NZ News for the ill-fated launch of the Sun, the same name that had been a force against the establishment in Auckland and Christchurch in the 1920s and 1930s under the mercurial Edward (Teddy) Huie. One of his legacies was the Star-Sun, which dropped its Sun tag in 1958.

Strong opinions and tabloid-style reporting was left to the non-magazine weeklies, which flourished through most of the century. Notable titles included the independently owned Free Lance, which lasted from 1900 until 1960 when it was absorbed into its main rival, the pictorial-heavy Weekly News from Wilson & Horton. Much more controversial was Truth, which had its own biography published in 2010.

Grant details one of its more notorious periods in 1970 when its 23-year-old editor, Russell Gault, moved its populism further right to support the US in the Vietnam war. He also launched a “birch the bashers” campaign.

Gault was soon replaced by Bob Edlin, who moderated the populism but also exposed ‘The Plot’ – a conspiracy of left-wing public servants (including WB Sutch) to “socialise” New Zealand under the then Labour Government.

Gault returned from South Africa as editor five years later, this time breaking the NZ Listener’s monopoly on TV listings. This gave Truth a second life as a celebrity-based publication based in Auckland under Alan Hitchens. Its demise in 2012 was largely due to a successful defamation case brought by singer Ray Columbus.

Hitchens was also prominent in the development of a strong Sunday press, which was first tried in Palmerston North from 1933-35 with the Sunday News. Legislation prevented anything being produced after 7pm on a Saturday for sale on Sunday. Evening papers got through a loophole with sports supplements, such as the 8 O’Clock and Sports Post. These were initially popular but had limited appeal to readers who already had a diet of expanded Saturday papers.

The first major attempt at creating a new market was Auckland’s Sunday News in 1964. It lacked capital and was bought by the owner of Truth. Ahead of a pending legislative change, Wellington’s Dominion-Sunday Times followed a year later. Wellington Publishing acquired both Truth and Sunday News, which flourished under Hitchens and then Judy McGregor, the first woman to edit a major newspaper.

The NBR office in Wellington’s Blair Street.

The Sunday News circulation rose to a peak of 220,000 but fell dramatically after 1985. The Dominion-Sunday Times made little headway in the Auckland market but was soon outselling its daily sibling. The switch to a broadsheet format as the NZ Times lasted five years until it reverted to the original title in 1986, dropped its Dominion moniker in 1992.

Meanwhile, in 1986, Forbes at NZ News had created an all-new Sunday Star to replace the 8 O’Clock. It was a substantial 64-page broadsheet, looked like USA Today, was an instant hit and also outsold its parent. In 1994, it merged with the Sunday Times as the Sunday Star-Times.

Over at Wilson & Horton, the Sunday Herald was launched in 1971 shortly after the closure of Weekly News. The new title lasted only five years. A replacement, the Herald on Sunday, did not appear until 2004.

Saving the best until last, The National Business Review first appeared in 1970 and was the only survivor of several weeklies launched in final three decades of the 20th century. Although its first 20 years are well covered in Sir Hugh Rennie’s A Business Revolution (2020), Grant provides another insider’s account of why it outlasted its rivals. The list of failures includes The Week (1976), The Nation (1980-81), The Examiner (1990-91), and The Independent (1992-2010).

Amid the corporate machinations and editorial changes, Grant provides a wealth of other information: how newspaper managers coped with wartime shortages of staff and newsprint (until local manufacturing in 1955 at Kawerau); the struggle in getting and paying for new presses and equipment; outbreaks of militant unionism by both journalists and printers; and the closed-shop nature of the New Zealand Press Association’s supply of domestic and international news. Coverage of political, religious, and community titles is also comprehensive.

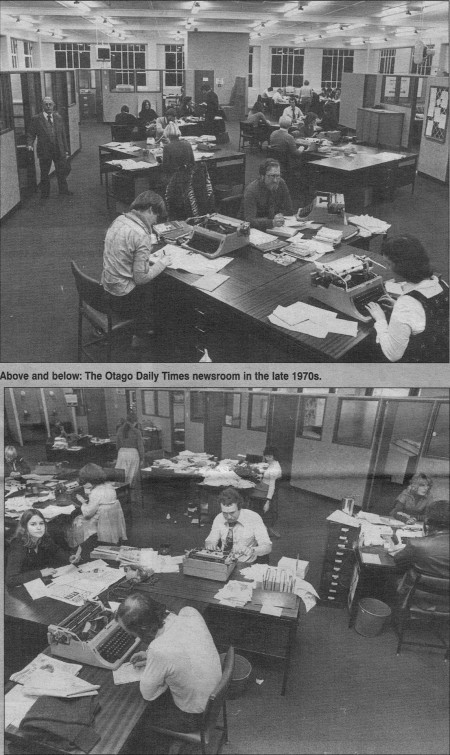

Innovation was never an industry priority, with a few exceptions. Provincial publishers were first with rotary offset printing and direct editorial input. Unions resisted technology that diminished the number of jobs. Illustrations were not common until the 1950s. The Press was one of the last to put news stories on the front page (1965). Uniquely, the Evening Post for a time did both with pictures on the top half and classified advertising on the bottom.

Resistance to overseas ownership resulted in a National Government passing of the News Media Ownership Act in 1965. It was repealed by a Labour Government in 1974. A bidding war for Wellington Publishing resulted in Rupert Murdoch gaining a foothold, although he agreed to restrict his voting shares. It was the start of another era but that will need a further book.

Disclosure: Nevil Gibson worked at several of the newspapers named in this review: The Dominion, Dominion-Sunday Times, Truth, The Press, and NBR.

Pressing On: The story of New Zealand newspapers, 1921-2000, by Ian F Grant (Fraser Books/Alexander Turnbull Library).

Nevil Gibson is a former editor-at-large for NBR. He has contributed film and book reviews to various publications.

This is supplied content and not paid for by NBR.