From buddy to bully: Kiwis’ encounters with China

Anthology marks 50 years of diplomatic ties with world’s largest communist state.

NBR columnist Nevil Gibson speaks with Fiona Rotherham.

Anthology marks 50 years of diplomatic ties with world’s largest communist state.

NBR columnist Nevil Gibson speaks with Fiona Rotherham.

Many readers will have had personal encounters with China over the past 50 years. Mine would not be dissimilar, starting with a brief day tour to Guangzhou by road from Hong Kong in the 1980s.

Like any visit to a communist country, tourists were under strict controls, including photography, learned little from their guides, but were able to observe the obvious signs of poverty, backwardness, and conditions that defied any idea that socialism was a superior system.

These notions had long been nurtured on the Left, through friendship societies, pro-communist ‘peace’ groups and, during the 1960s and 1970s, opposition to the Vietnam War and nuclear weapons.

In 1972, the first actions by newly elected Labour governments in New Zealand and Australia were to recognise the People’s Republic of China as the sole legitimate successor to Chiang Kai-shek’s Nationalist regime.

This had nothing to do with New Zealand’s economic interests and everything to do with political ideology.

Ironically, the National Party did much to advance the economic and political relationship while in power, with Sir Robert Muldoon being the first prime minister to visit China, in 1976. And it was a National Party dominion councillor, Victor Percival, who was the most ardent champion of doing business with China, promoting trade.

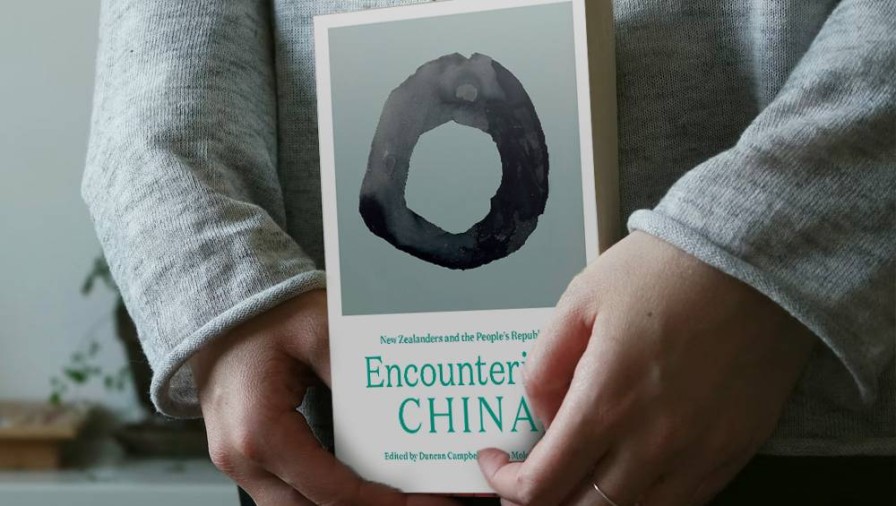

The establishment of formal diplomatic ties is marked by a new book, Encountering China, which collects the experiences of more than four dozen diplomats, academics, students, writers, artists, and others who travelled and lived in communist China.

But ,as my daytrip revealed, the first three decades of communism remained hidden from all but a few outsiders. The purges and famines that killed tens of millions of Chinese under communism after 1949 – more than all the deaths during World War II blamed on Hitler and Stalin – could not be verified.

Immediately after the establishment of diplomatic ties, a trade union mission, including Tame Iti and poet Hone Tuwhare, visited China, not long after one in 1971 representing university students. Meanwhile, China’s most famous Kiwi, Rewi Alley, stepped up his flow of articles and speaking tours on behalf of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP).

Encountering China co-editor Brian Moloughney.

Trade and business ties were still non-existent. China’s opening and reform period did not start until 1982, six years after the deaths of Mao Zedong and Zhou Enlai. My next visits came after the June 1989 massacre of demonstrators in Tiananmen Square, which ended a period of threat to the CCP’s monopoly of power.

This is vividly recounted by one of the book’s editors, Brian Moloughney, a foreign student at the time.

In the 1990s, I revisited Guangzhou on a trade-related trip, travelling by train through the new metropolis of Shenzhen. I also went to Shanghai and Wuxi after the handover of Hong Kong in 1997. China’s transformation was well under way. Bicycles were still the main form of transport in Wuxi, a provincial city on the Yangtze River, and the motorway from Shanghai had little traffic.

Highways were just part of the top-down strategy of building high-rise office towers, residential apartment blocks, factories, railways and airports as the primary signs of socialism.

When a Labour government was returned to power in 1999, its ideological fixation toward China was reflected in support for a fully state-controlled economy to be worthy of World Trade Organisation membership. That was rewarded in 2008 with a free trade agreement, signed by Trade Minister Phil Goff with Prime Minister Helen Clark attending.

Finally, New Zealand and China embarked on a period where business and limited tourism could thrive. Subsequent visits, including a pre-Olympics one to Beijing, showed me a dynamism that astonished Westerners used to democratic processes that hindered rather than fostered growth and expansion.

It seemed obvious that investment by Western capitalists and expanding trade ties would cement China’s place as the world’s factory for consumer goods and, in return, it would buy as much food as New Zealand could produce. Rising middle class prosperity would ‘democratise’ China, just as it had in Taiwan, and China would be an admired member of the world community.

Sadly, it was not to be. The reversion to Maoist-style one-man rule was not a surprise to some. Subsequent accounts revealed CCP commitments to an autonomous Hong Kong were worthless. The party state, to use the shorthand of the editors of Encountering China, was not going to loosen its grip on power.

Encountering China co-editor Duncan Campbell.

Classical Chinese expert Duncan Campbell – the co-editor who studied in China from 1976-8, and has taught at universities in Wellington, Auckland, and Canberra – observes that President Xi Jinping’s advocacy of “Chineseness” has been “established at the expense of the brutal eradication of a multiplicity of alternative political and cultural entities”.

Campbell goes on to describe China as a society “characterised by a catastrophic collapse in trust” at home and abroad “acts with the swagger of a playground bully”. His criticisms put the 50 contributions into context, as only a handful tackle the hard issues of China’s rejection of a rules-based world order; its repression of Tibetans, Uyghurs and other minorities; its lack of opposition to the Russian invasion of Ukraine; and its aggression toward 15 of its Asian neighbouring states, including Taiwan.

Campbell is not the only one whose disillusionment is obvious.

New Zealand Contemporary China Research Centre director Jason Young describes academic exchanges that have little value apart from personal experiences, such is the control of the party-state over intellectual life.

Alex Smith, who embraced Chinese language and culture for a career, returned to New Zealand to pursue other opportunities. She quit working for a think tank in New York because of the “anaconda in the chandelier” – a reference to the threat she felt between choosing compromise or being denied access.

One strand of the New Zealand-China relationship that never felt that pressure was the Communist Party of New Zealand. In one of the most revealing contributions, Massey University Professor Kerry Taylor tracks the career of Vic Wilcox, who was funded by the CCP since the 1960s for running the only Western communist party that switched its allegiance from Moscow to Beijing.

Despite his many visits to China, where he was regularly depicted on the front page of the People’s Daily with Mao and Zhou as a ‘statesman’ from New Zealand, Wilcox eventually fell foul of party infighting and was expelled in 1978.

In 1970, he had done this to the Wellington ‘gang’, which retained close ties with the Chinese embassy after it opened 1973. Wilcox was accused of being “lazy” and a drunk by a hardline group that followed Albania as the only pure Maoist party after China changed tack under Deng Xiaoping.

Apart from the personal reminiscences, which largely eschew political analysis, some of the sympathetic chapters reflect the academic fashion for racial and colonisation frameworks. The absence of a gender one, despite a third of the contributors being women, is notable, given Xi’s politburo having no women.

However, Pauline Keating’s tribute to environmental activist Dai Qing does mention that when China staged the UN’s Fourth World Conference on Women in 1995 it had no legal non-government organisation representing women (or any other civil grouping for that matter).

Victoria University academic Hongzhi Gao.

A teacher of Chinese religion, Amy Holmes-Tagchungparta, describes the difficulty faced by her study of Tibetan Buddhism, while apologists are countered by the gratefulness of one Chinese, Hongzhi Gao, that he moved here rather than stayed there.

He is now an associate professor of marketing at Victoria University and gives a trenchant reminder of his warning a decade ago that China plays only by its own rules. He warns about doing business with China without knowing how its products are made, how its labourers are treated, how its environment is protected, how intellectual property are treated, and how Chinese consumers view foreign goods.

“It is dangerous to be focused only on trade and to ignore other important topics,” he writes, noting that while Kiwis take for granted attributes of transparency, fairness, freedom, and democracy, this is not the case in China.

He urges the Taoist yin-yang approach of “dynamic balancing” – that the values shared with Australia, the US, and other Western allies cannot be given lower priority than China’s closed ‘insider-controlled’ market for foreign businesses.

His message is the main takeaway from a book that illuminates much about some New Zealanders’ experiences with China and concludes that, for the moment, the Golden Age of the first two decades of this millennium is over.

Encountering China: New Zealanders and the People’s Republic, edited by Duncan Campbell and Brian Moloughney. (Massey University Press).

Nevil Gibson is a former editor at large for NBR. He has contributed film and book reviews to various publications.

This is supplied content and not paid for by NBR.

Sign up to get the latest stories and insights delivered to your inbox – free, every day.