Freud’s exit from the ‘laboratory of the apocalypse’

The founder of psychoanalysis sensationally escaped the Nazis.

NBR columnist Nevil Gibson speaks with Calida Stuart-Menteath.

The founder of psychoanalysis sensationally escaped the Nazis.

NBR columnist Nevil Gibson speaks with Calida Stuart-Menteath.

A couple of weekends ago, Auckland’s Spark Arena was completely full. This was not unusual for a pop concert or sporting event. But in this case, it was a speaker, Jordan Peterson, who shared the stage with wife Tammy.

In many ways, it was a psychoanalytical session lasting a couple of hours in which Peterson answered the concerns of his audience.

Peterson attracts controversy because his views on society and solutions to its ills do not fit with the prevailing hostility to religious belief, that individuals should be responsible for their own actions, and that men and women have different perspectives on life.

His views on the latter topic are socially conservative, even traditionally conventional, while his dislike of nanny governments, socialism, and collectivist rules are appealing to libertarians.

Jonathan-Castellino-web.jpeg)

Jordan Peterson.

Jordan’s appearance was unreported in the media, though I did see some mention that a handful of feminists had sought to have the session cancelled, as is common practice in some quarters.

He noted his visit had attracted only a handful of protesters and that a hundred times more had turned out to demonstrate against his presence in Berlin.

For the record, the questions chosen from the hundreds logged on weren’t that challenging: cohabitation before marriage; the government-funded centre for research on disinformation; sex change for teenagers; carbon taxes; free trade; and globalisation.

Each ranked an answer lasting up to half an hour, giving plenty of opportunity to watch Peterson turn the many facets of these issues into nuggets of wisdom, with the audience applauding to greater or lesser extent when he reached a conclusion.

Before he was elevated to guru status, Peterson was a practising clinical psychologist and therefore can base his arguments on personal case studies as well as centuries of learning from the past.

My description of the session as an exercise in mass psychoanalysis for those interested in coping with depression, relationships, parenting, anxiety, and other ailments loosely known as mental illness is appropriate because it steeped in the work of Peterson’s predecessors such as Sigmund Freud.

Peterson began his answer on the topic of facts and opinions in a freedom of speech question with Freud’s notion of the human psyche being a battleground for ideas. Attempts to define what ideas are acceptable, or not acceptable, in this context are the opposite of freedom.

To quote from Peterson’s 12 Rules for Life: “A fact [is dead]. It has no consciousness, no will to power, no motivation, no action … But an idea that grips a person is alive. It wants to express itself, to live in the world.”

This explains why Peterson offends politicians and others who want to shut down the debate of ideas. “[An] idea has an aim. It wants something. It posits a value structure.”

I suspect this is what appealed to his audience, many of whom might have felt they are being ostracised, shut down, or penalised for their ideas.

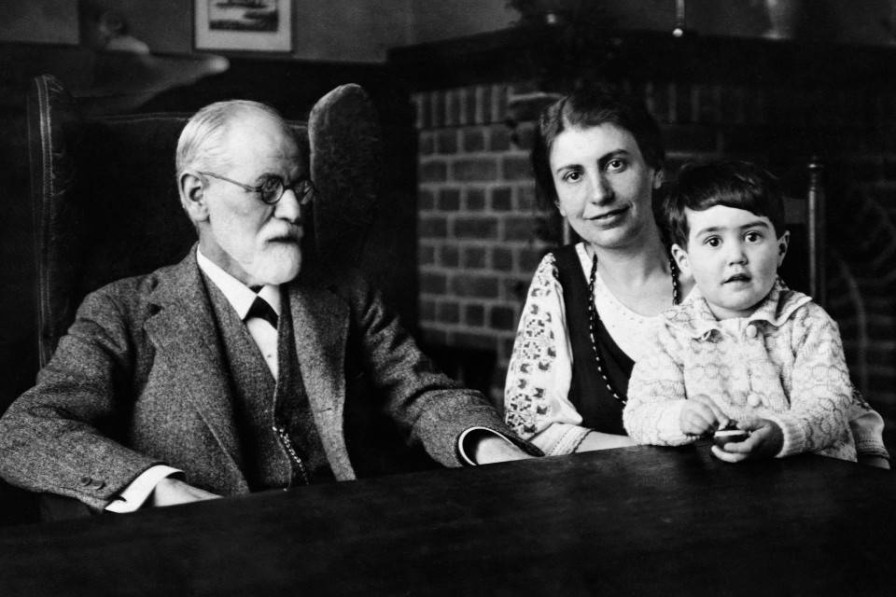

Sigmund and daughter Anna Freud began working together in the 1920s. The identity of the child in this photo isn’t known.

Freud’s life of discovery, and those who engineered his escape from Nazism, is the subject of Saving Freud, by Andrew Nagorski, a former correspondent for Newsweek and the author of several books on Nazi Germany and post-war communism in Eastern Europe.

Freud’s bold claim is: “Psychoanalysis simplifies life. [It] supplies the thread that leads a man out of the labyrinth.” He developed notions of the id, which is driven by inherent instincts; the ego, which tries to control those instincts; and the superego, which is shaped by parental and other early influences.

Peterson underlined these when he said anti-social and criminal behaviour was “baked in” during infancy and lasts into adulthood. The therapist’s job is to find the deep-seated reasons for a person’s behaviour and neuroses.

Freud was born to Jewish parents in a Moravian village that is today part of the Czech Republic, or Czechia as some are calling it. The Austro-Hungarian Empire, run by the Habsburgs, was not a colonising force as others from Europe have since been branded.

It was home to 50 million people who represented nine major nationalities and numerous minorities. Its capital Vienna was the most multicultural in Europe and, as Nagosrki puts it: “The Habsburg rulers granted diverse subjects and regions limited yet impressive autonomy, allowing them to set many of their own rules while trading and travelling.”

Not surprisingly, this was a “recipe for political and economic success” that rested on a built-in willingness “to tolerate the ambiguities, contradictions, and tension inherent in such a relatively enlightened multinational, multicultural arrangement”.

Freud was not alone among the world’s intellectual giants to thrive in such as environment. Vienna in the late 19th century was also home to composers such as Mahler and Schoenberg, writers Zweig and Roth, as well as physicians, physicists, and psychologists.

Although they made up only 10% of the population in 1880, this elite was dominated by Jews, who were prominent in the arts, science, medicine, and publishing. Emperor Franz Josef had encouraged this when he removed special taxes and restrictions on Jews in 1848 and, in 1867, granted them full citizenship.

This didn’t end anti-Semitism but it enabled Freud to keep his Jewish identity even though he didn’t practise the religion. In his private life, as with Peterson, he had a lifelong marriage to Martha Bernays, despite rumours of an affair with Martha’s sister Minna. They produced six children between 1887 and 1895.

Berggasse 19: Freud’s home and now museum.

In 1891, the family moved to Berggasse 19, where they remained until 1938. Freud’s fame spread, helped by his association with Swiss psychoanalyst Carl Jung, and was bolstered by books such as one on hysteria (1895) and dreams (1899).

Welsh-born Ernest Jones became Freud’s main acolyte in the English-speaking world and the pair had a lifelong collaboration that didn’t end until Freud’s death in 1939, 15 months after his dramatic escape to England and just 20 days after Britain’s declaration of war.

Nagorski tracks the parallel rise of Adolf Hitler and the anti-Semitism that led to the Holocaust. Born in rural Austria, Hitler first visited Vienna in 1906 and was in awe of its architecture. That changed in 1908 when he was rejected as a student by the Academy of Fine Arts, later describing his five years in Vienna as the “saddest” period in his life.

One writer, noting the role of Vienna as the crucible for both the ‘Jewish science’ – as psychoanalysis was disparagingly known – and virulent anti-Semitism, called the city “the laboratory of the apocalypse”.

Meanwhile, in 1909, Freud, Jung, and others took their psychoanalytical teaching to the US. World War I broke up the Habsburg Empire, leaving Austria as a rump of 6.5 million people. One of the outcomes was the boost to psychiatry from the mental effects on war victims.

Previously considered as an excuse for malingerers, the damage of post-traumatic stress disorder became widely recognised. The 1920s and 1930s enabled Freud, along with his daughter Anna, to build a substantial practice that attracted worldwide attention.

Hitler addresses thousands at Heldenplatz on March 15, 1938.

Freud’s health, including cancer of the jaw, had become a serious impediment to his work and it was only with Jones’s intervention that Freud was persuaded, at 82, that he and his entourage of 16, including Martha and Minna, should escape the Nazi menace. Hundreds of thousands of Viennese welcomed Hitler back on March 15, 1938, when Austria joined the Third Reich.

Final persuasion occurred when the Gestapo arrested Anna. Freud had first visited England, as a 19-year-old, in 1875 and was struck by the people’s “sober industriousness” if not the damp, foggy weather, the extent of drunkenness, and their conservatism.

Nagorski recounts the first visit by the Nazis to Berggasse 19, which now houses the Freud Museum. They took all the cash, some 6000 schillings (then worth about $US840), but the tortuous process to extract the Freud retinue from the country involved the work of many, including socialite and psychoanalyst Princess Marie Bonaparte, American diplomat William Bullitt, and a sympathetic Nazi-appointed commissar Anton Sauerwald, who handled the archives and accounts. He was later charged for his Nazi affiliations, partly at the behest of Harry Freud, Sigmund’s nephew and a US Army officer.

Not all the family survived. Freud’s four elderly sisters died in concentration camps. Nagorski’s account emphasises the personal role of people in Freud’s life rather than his work, which has been extensively documented elsewhere. This is a readable introduction to Freud’s impact and, as Peterson demonstrated, it is one that continues to be felt.

Saving Freud: A Life in Vienna and an Escape to Freedom in London, by Andrew Nagorski (Icon Books).

Nevil Gibson is a former editor at large for NBR. He has contributed film and book reviews to various publications.

This is supplied content and not paid for by NBR

Sign up to get the latest stories and insights delivered to your inbox – free, every day.