Finlayson’s verdict: The nearly perfect minister

Former Attorney General sums up the John Key years.

NBR columnist Nevil Gibson speaks with Fiona Rotherham

Former Attorney General sums up the John Key years.

NBR columnist Nevil Gibson speaks with Fiona Rotherham

The least readers should expect from a memoir is to be factually accurate and a contribution to the greater sum of human knowledge. Many fail this test, relying on memory and oral recollection rather than diaries, written notes and the public record.

Celebrity memoirs, usually ghost written, are often deficient in the fact department but make up for it with juicy gossip and score-settling. Literary memoirs combine both, as correcting the record is important for writers and their legacy.

Business memoirs are the least valuable, especially the self-published kind, as they lack the detail that should come with inside knowledge. Only a handful provide material that has value to future generations.

That leaves political memoirs, which while largely concerning matters of public record can provide new insights into government decision-making and power plays.

Recent contributions from Labour politicians Sir Michael Cullen and Margaret Wilson have stood out for their in-depth accounts. On the National side, Simon Bridges and Judith Collins were more concerned with establishing a personal legacy. But their brief stints as leaders in opposition offered little for posterity.

Christopher Finlayson outside Parliament Buildings.

Stepping up

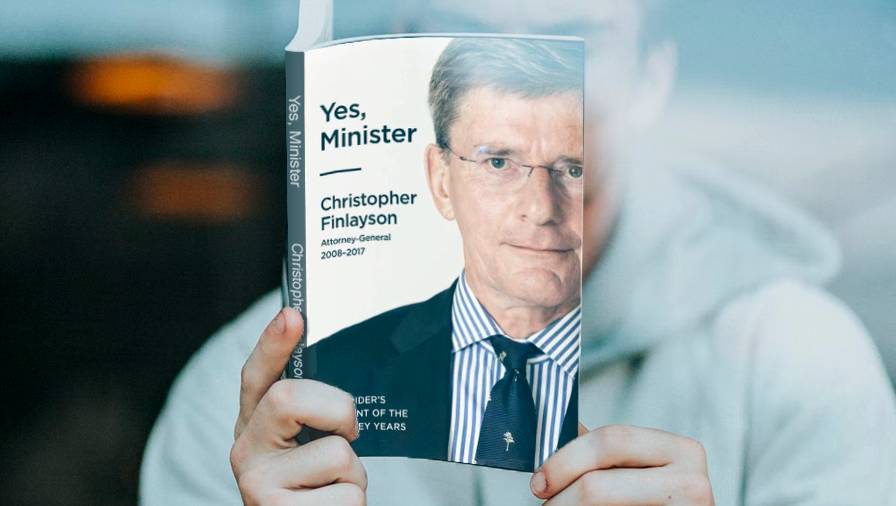

That leaves Christopher Finlayson to step up with Yes, Minister, his account of being Attorney-General in the John Key- and Bill English-led governments from 2008-17. It’s a contrast to Andrea Vance’s Blue Blood, a racy outsider’s view that is heavily dependent on anonymous sources for its “insider” account of National’s political machinations over 14 years.

Finlayson covers the same period. Indeed, he is often quoted by Vance, who might as well have had a sneak preview of his manuscript. While the publicity surrounding both books focused on personalities and failures in political strategy, Finlayson’s legal background gives him the advantage of the rare detachment that came with his coveted appointment in a role that has distinct historical roots.

The first attorney-general was a 15th century custom that allowed the English monarch to be represented in a court of law. The convention evolved into a political position that provides legal advice to the government as well as uphold the Crown’s role in the judicial system.

Properly done, the attorney general could advise his or her cabinet colleagues that their proposed actions are against the law, a task Finlayson took seriously and appears to have dented any other political ambitions he may have entertained.

This perspective gives him an aloofness to events around him and his now well-known views of his colleagues and opponents, which need not be repeated here. He attributes his unscathed political reputation to timing as much as his superior intelligence.

Timing is crucial

Timing is everything in politics, and Vance’s book reveals many who got it right and wrong. Finlayson’s first parliamentary term was in opposition to a declining government. It gave him three years’ experience you can’t get if you are new MP for a party in a government’s first term.

John Key's first cabinet, 2008 (Christopher Finlayson is fifth from the left).

Nine or six-year governments are the norm, so Finlayson was a sitter for John Key’s cabinet in 2008. Contrast that with the plight of Labour backbench MPs swept into power on the 2020 Covid tide and likely to go out again next year.

Finlayson’s other advice to would-be MPs is to focus on a few issues where you have expertise. He is critical of the trend toward careerist politicians, who move from university into parliamentary roles as advisers with no experience of the world outside politics.

As a lawyer with court experience here and overseas, Finlayson is shocked by how slow the dispensation of justice has become, with cases being extended through procedural issues to extract fee income. He recalls with fond memory the days when judges delivered oral judgments immediately after hearing a case. Today, some judges delay their decisions for months if not years.

As a minister, he was successful in reducing the number of outdated statutes, and worked with the opposition to gather bipartisan support for some measures. One example was legislation relating to the collection of security intelligence while he was minister of the relevant government agencies.

At other times he failed, blaming the “perfidy” of oppositional politics and entrenched interests. One egregious example was the outcome of a lengthy consultation over Māori land legislation. The final hurdles came too late in the National government’s final term to pass into legislation.

Labour ditched the reforms after 2017 election, an action he describes as “unprincipled and unreasonable,” given the effort that had been put in across the political spectrum. Finlayson is also scathing about Labour and Māori attitudes to the mixed ownership model that partly privatised the state’s electricity generation companies and Air New Zealand.

Labour had countered with an ill-fated proposal on power pricing, which Finlayson describes as the “greatest act of political bastardry,” adding that it was “incoherent and unprincipled.” Māori Council and Waitangi Tribunal interventions showed they were out of their depth and “struggled with complex economic issues".

Border closure ended New Zealand's role as Middle-earth. Photo: Amazon Studios.

Finlayson was also in his comfort zone as the minister for arts, culture and heritage, where he despised the unions acting against the interests of the film industry in the Hobbit agreement with Warner Bros. (The Adern government’s border closure finally ended Hollywood’s fling with New Zealand as Middle-earth.)

Others on Finlayson’s disapproval list are the Ministry of Education promoting anti-colonialist history (“essentially propagandists”), the Law Society’s left-wing agenda, and churches promoting social justice rather than religion. On the latter, quoting from the TV programme that gave his book its title, he cites Sir Humphrey Appleby: “These days politicians want to talk about God, and the clergy only want to talk about politics.”

It’s hard not to like Finlayson’s defence of neoliberalism, though he doesn’t profess to have economic skills, and his admiration for the Rogernomic reforms. On his to-do list for future National governments are the abolition of the Waitangi Tribunal, the Human Rights Commission and Landcorp, the government-owned agricultural business. He would also like to see a merger of government enterprises into Singapore’s Temasek model (also advocated at one stage by Shane Jones), and the restoration of public service as an apolitical agent of a reduced state.

Another on his wish list is the incorporation of property rights into the Bill of Rights, which would have the side benefit of guaranteeing Māori land entitlements better than existing laws. Finlayson has already produced one book from his time in office, He Kupu Taurangi, on his treaty settlements, and he is promising another on the rule of law.

That should further enhance his reputation as the nearly perfect minister – one who left the country better off than he found it and knew when to move on.

Yes, Minister, by Christopher Finlayson (Allen & Unwin).

Nevil Gibson is a former editor at large for NBR. He has contributed film and book reviews to various publications.

This is supplied content and not paid for by NBR.

Sign up to get the latest stories and insights delivered to your inbox – free, every day.