Fact and fiction in James Bond

Scientist assesses the spy’s exploits, weapons, technologies, and villains.

NBR columnist Nevil Gibson speaks with Will Mace.

Scientist assesses the spy’s exploits, weapons, technologies, and villains.

NBR columnist Nevil Gibson speaks with Will Mace.

Somewhere between the heightened reality of Cold War espionage thrillers and the comic book superhero universes lies the movie franchise of James Bond.

It’s an entertainment juggernaut that in 60 years has produced 25 films from a base of 14 books, including two volumes of short stories, produced by Ian Fleming between 1953 and 1966. The books started with Casino Royale, which was adapted for television in 1954, and the movie series proper started with Dr No in 1962.

Storylines and characters created by Fleming have long been exhausted, prompting other writers to fill the vacuum. Kingsley Amis set the balling rolling with Colonel Sun in 1968. He was followed in 1981-96 by John Gardner, who wrote 14 Bond thrillers before Raymond Benson took over with six novels, three novelisations and some short stories between 1996 and 2000.

Since then, several other notable authors have been commissioned to continue the series: Sebastian Faulks (Devil May Care, 2008), Jeffrey Deaver (Carte Blanche, 2011), William Boyd (Solo, 2013) and Anthony Horowitz (Trigger Morris, Forever and a Day, and With a Mind to Kill, 2015-22). On top of this, Charlie Higson and Stephen Cole produced nine books featuring a young James Bond set in the 1930s.

Most of these post-Fleming books are unrelated to the movie franchise, which Fleming signed with the Eon company owned by producers Harry Saltzman and Albert “Cubby” Broccoli. The franchise is now controlled by Barbara Broccoli and her half-brother Michael Gregg Wilson.

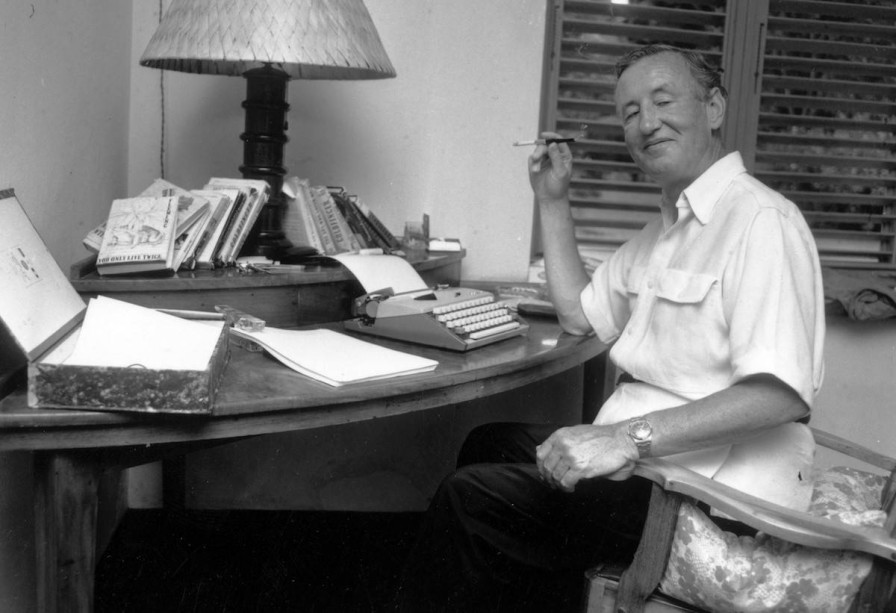

Ian Fleming injected his own habits into the character of James Bond.

It was this deal that outlined Fleming’s conditions and established the formula that characterises every Bond film – except for an outlier Casino Royale (1967) that was later remade in the conventional mould in 2006 after Eon bought the full adaptation rights to all the books. (Another non-Eon production, Never Say Never Again (1983), was a remake of Thunderball that resulted from a court decision in favour of one of the original film’s writers.)

Series reboot

Casino Royale (2006) was something of a series reboot, with New Zealand-born director Martin Campbell and Daniel Craig as Bond putting a greater emphasis on the 007 character and his background. This approach continued in the remainder of the films up to his apparent death in 2021’s No Time to Die. Though the end credits promised, “James Bond will return,” to date, little has emerged on a 26th movie.

In the meantime, readers can browse through a dozen or more books written by experts on various aspects of the movies: the politics (2001), the science (2020 and 2006), treatment of women/gender (2020), bedside companion (1984), encyclopedia (2015) and cultural impact (1999).

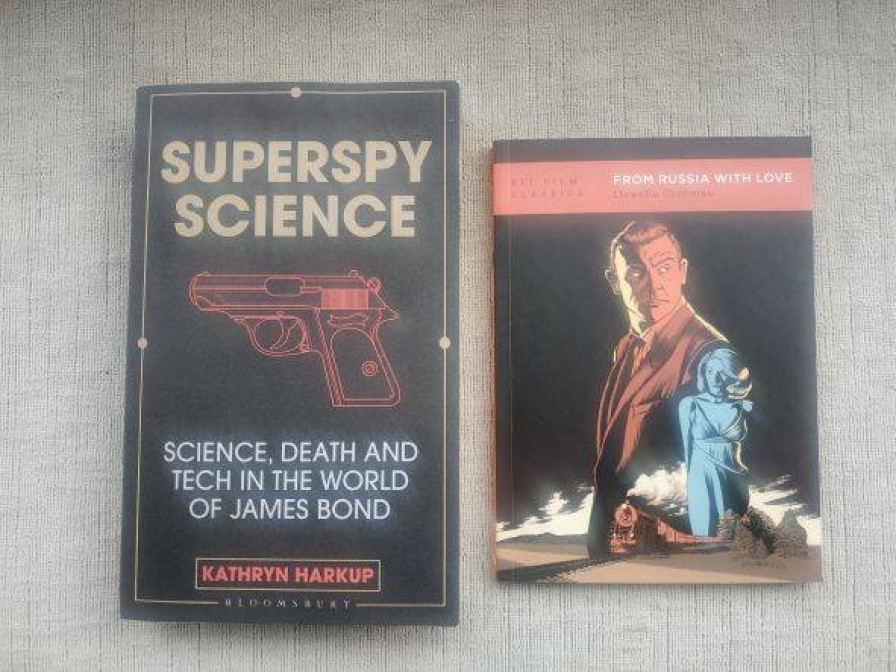

The latest is Superspy Science, a study of the gadgets, technology, and villainous plans for world domination in the light of actual science by scientific chemist-turned-author Kathryn Harkup, who wrote A is for Arsenic: The poisons of Agatha Christie. Harkup has also written studies of death in Shakespeare and the science in Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein.

Each of the 25 chapters in Superspy Science examines an element from the 25 movies to illustrate the broad pathway from the relatively low-tech Dr No and From Russia With Love to the big-budget blockbusters expected by today’s audiences.

“Each new cinematic addition is simultaneously comfortingly familiar and new and exciting,” Harkup writes, while outlining the dozen critical elements that comprise a Bond movie.

These are:

* opening sequence with an intrigue, usually an assassination;

* Bond is briefed on his mission, and

* equipped with an array of gadgets;

* mission takes him to exotic locale/s;

* he uncovers a bigger than feared plot;

* meets ‘good and ‘bad’ women;

* survives attempts on his life, before

* meeting villain in his lair, which

* is an elaborate, secluded hideaway;

* villain outlines plans for world domination while torturing Bond;

* the lair is destroyed, and

* Bond gets the ‘good’ woman.

These ingredients are mixed with a series of quips (usually involving sexual innuendo), stunts, car chases, explosions, over-the-top sets, and cocktails.

Fleming’s legacy

All are informed by Fleming’s own life as an intelligence officer, pursuits such as golfing and gambling, a taste for luxury, and addictions (he died aged 56) as well as his interests in weapons, expensive vehicles, jewellery, poisons, and deadly animals, plants and sea creatures.

Fleming’s official description of Bond includes qualities such as quiet, hard, ruthless, sardonic, and fatalistic. He is patriotic to Queen and country but lacks personal beliefs or spirituality, though he will act out of altruism, especially if an attractive woman is involved.

He is assisted or impeded by futuristic machines, space stations, satellites, and other advanced forms of technology, often ahead of their actual development. Sometimes the identities of his enemies are based on real-life figures, such as media moguls Rupert Murdoch and Robert Maxwell, and Central American dictator Manuel Noriega.

A laser beam threatens James Bond (Sean Connery) in 'Goldfinger.'.

Markup thoroughly dissects these details, noting: “Bond films are not known for their strict adherence to scientific fact or narrative logic but … not all of it is made up.” Laser rays (Goldfinger), bio-weapons (On Her Majesty’s Secret Service), the nuclear threat (Dr No, Octopussy), gene therapy (Die Another Day) and changing Cold War tensions (From Russia With Love, The Living Daylights) were highly topical, though Bond eschewed conventional politics.

While “The scientific credibility may be stretched … the engineering and technical skill … is undeniably first class,” Markup observes. “Discovering new and unusual ways to use something as ordinary and everyday as electricity to kill people is all part of the fun [For Your Eyes Only].”

Traditional qualities

But this commitment to technological change doesn’t apply to all parts of the Bond tradition. The producers have largely avoided computer generated imagery, preferring to stage the daring stunts in real life and physically creating the monster sets before destroying them.

The deadly animals are not created by animation. These crocodiles and sharks are “creatures with very sharp teeth and with healthy appetites,” but according to Markup are not as lethal as depicted. The crocodile farm scene in Live and Let Die was real. Fortunately, it was the farm’s owner who accidentally performed the stunt of running over the crocs’ backs.

The scripts have failed to keep up with social trends. “The women in the Bond films have certainly become more complex characters over time, with their agency and with greater roles to play, but their relationship with Bond has not changed as much as we might like to think,” Markup writes.

One positive change has been dropping Fleming’s use of excruciating names for some of his female creations: Honey Ryder, Holly Goodhead, Pussy Galore, and Plenty O’Toole. But sex remains an essential part of Bond’s audience appeal. He slept with 58 women in his first 20 movies, far more than the 14 in the 12 books.

Rosa Klebb (Lotte lenya) and Tatiana Romanova (Daniela Bianchi) in 'From Russia With Love.'

Characters seeking same-sex activity remained locked in Fleming’s original conceptions, most notably in Lotte Lenya’s Rosa Krebb, who makes advances toward Daniela Bianchi’s Tatiana Romanova in From Russia With Love.

This is generally considered the pick of the bunch. The British Film Institute bestowed this honour in the latest of its BFI Classics series, scholarly monographs on the world’s most notable movies.

No Time to Die played up Bond’s ageing and increasing physical frailty. It undermined much of the Bond formula, perhaps opening the possibility of the next James Bond being a woman, gay or other than a British white male. This would, of course, mark a new direction altogether, one that could destroy the franchise. So would villains without disfigurements or disabilities and a liking for cats.

Whatever happens, it’s certain the film will come under the same scrutiny as Superspy Science has done for the first 25 while also meet the entertainment demands of several billion who have watched a movie or the 100 million who have read at least one of the books.

Superspy Science: Science, death and tech in the world of James Bond, by Kathryn Harkup (Bloomsbury Sigma).

From Russia With Love, by Llewella Chapman (BFI Classics/Bloomsbury).

Nevil Gibson is a former editor at large for NBR. He has contributed film and book reviews to various publications.

This is supplied content and not paid for by NBR