Ethics and empire: Judging the morality of colonialism

One man’s battle for free speech in the culture wars.

Colonialism: A Moral Reckoning, by Nigel Biggar.

One man’s battle for free speech in the culture wars.

Colonialism: A Moral Reckoning, by Nigel Biggar.

English clergyman, ethicist, and historian Nigel Biggar doesn’t seem the type to be up for a fight. But, at 69, he is a leading warrior in the cultural war against academic ideologies that downgrade the Enlightenment values of Western civilisation in favour of critical theory, indigenisation, and decolonisation.

For most of his career, Biggar led a quiet life studying and teaching Christian theology in the UK, Canada, United States, and Ireland. In 2007, he was appointed Regius Professor of Moral and Pastoral Theology at the University of Oxford.

He was ordained as an Anglican priest in 1991 and became a canon of Christ Church Cathedral, Oxford. His books included several with ethics in their title. His conservatism was reflected in a justification for the use of violence against repression, In Defence of War (2013), and denying the existence of natural rights, What’s Wrong with Rights? (2020).

His warrior status was earned in 2017 when he launched a research project, Ethics and Empire, which triggered immediate condemnation from historians and academics who equated imperialism with an extensive list of sins, ranging from genocide and slavery to colonialism and racial subjugation.

These scholars rejected the tradition of the Enlightenment and its basis in scientific rationalism, capitalism, and universal rights as inherently immoral and reflective of white supremacy. Their thesis was a reinterpretation of how Western capitalism spread throughout the world from the late 18th and 19th centuries.

That Biggar was challenging this view from a moral perspective was too much for someone such as Dr (now Professor) Priyamvada Gopal of Cambridge University and later author of Insurgent Empire: Anti-Colonial Resistance and British Dissent (2019).

She texted her colleagues: “OMG. This is serious shit … We need to SHUT THIS DOWN.” Biggar received the message as he and his wife were on their way to Nuremberg to celebrate their 35th wedding anniversary.

Professor Nigel Biggar at the Free Speech Union meeting in Auckland.

What happened next was a story that Biggar has told many times. He told it again last weekend at the annual meeting of the Free Speech Union in Auckland. It’s one of how an academic cancellation backfired.

As he tells it, Oxford’s establishment held steady – where many others haven’t – and his research project ran its full five-year term. The attempt to ‘shut this down’ produced its own backlash.

A publisher, Bloomsbury, commissioned an “intelligent person’s guide to colonialism” based on Biggar’s research. He completed it but was then told that “public feeling was unfavourable” to publication. Biggar soon found another publisher, HarperCollins, which released it in February last year as Colonialism: A Moral Reckoning.

Conservative and pro-free speech academics rallied to his cause, partially thanks to publicity in the right-leaning section of the British mass media: The Daily Telegraph, The Times, and The Daily Mail.

Sympathetic historians formed an association, History Reclaimed, with members from throughout the world. Its website has three New Zealanders on its recommended reading list: Professors James Belich (now at Oxford), and AUT’s Paul Moon, as well as the late Michael King.

Free Speech Union founder Toby Young during his New Zealand speaking tour earlier this year.

Another outcome was the free speech movement, launched in the UK by Spectator columnist Toby Young in February 2020. Biggar became its chair. The Free Speech Union has spawned similar organisations in Australia, South Africa, and Canada, as well as New Zealand. They focus on legal cases as well as entrenching rights to freedom of speech for teachers and students in universities. They also oppose governments passing ‘hate speech’ laws.

At the FSU meeting in Auckland, as well as in appearances at Wellington and Christchurch, Biggar had little opportunity to discuss the content of Colonialism: A Moral Reckoning, which to my knowledge had no exposure here on its first release.

It now has an updated edition that runs to nearly 600 pages, including a 70-page postscript, in which Biggar responds to his severest critics, among them supporters of Gopal’s ‘shut this down’ campaign. Biggar’s reply increases the source notes to more than 130 pages (which contain some of the best content), and a rich bibliography of 33 pages.

Critics of Biggar and others who challenge the anti-colonial view emphasise the role of race and violence along with economic exploitation and land seizure. This was the case in New Zealand, as well as in North America, Africa, India, and Australia where the British Empire had its biggest impact.

Biggar responds by accusing his critics of exaggerating or distorting the evidence and applying judgments based on modern-day sensibilities rather than those prevailing at the time. He accuses them of adopting a higher moral ground, which makes them vulnerable to seeing only the worst in people of their own kind – something he calls “Christian degeneracy”.

While this has some virtue in recognising sin, it also contains the seeds of vice, he warns. “For it can degenerate from genuine humility into a perverse bid for supreme righteousness, which exaggerates one’s sins and broadcasts the display of repentance: holier-than-thou because more sinful-than-thou.”

Fortunately, this moralising does not hinder the book's main narrative, which examines in great detail over eight chapters the main accusations against the British Empire from its origins in Ireland to its dismantling after World War II.

The early chapters focus on the motivations for imperial expansion, which of course began well before the British example; the role of Britain as the first imperial power to abolish slavery; and the belief, espoused by Christianity and the Enlightenment, in the equality of all peoples. At the centre of the imperial project was the idea that all societies could advance if given the right tools for development.

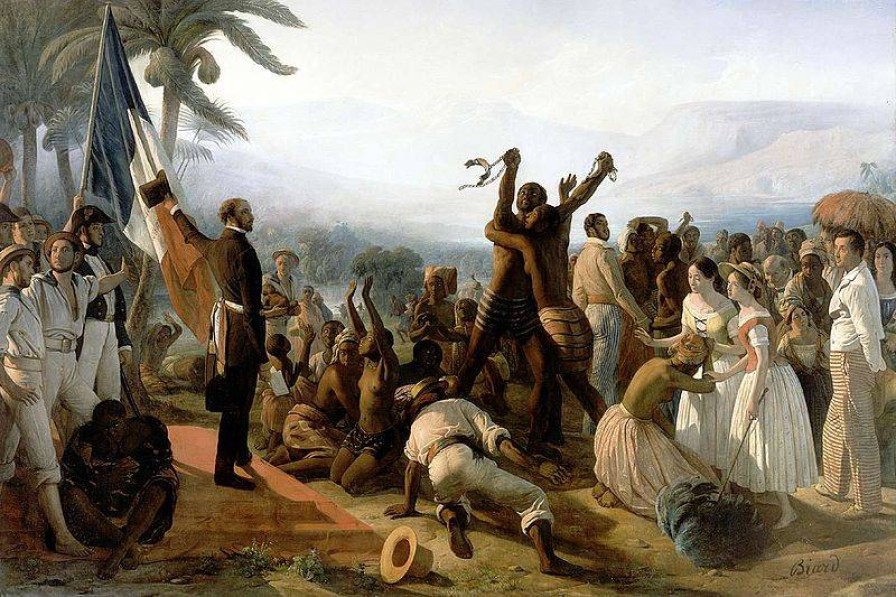

Francois-Auguste Biard’s painting of the proclamation of the end of slavery in the French colonies in 1848.

The British Empire, like the Roman one before it, lacked centralised power until modern forms of communication were invented leading up to World War I. These enabled the empire to draw on support from its colonies against the combined forces of Germany, Austria-Hungary, and Ottoman Turkey.

The use of land for settlement, agriculture, or other forms of exploitation is more complicated than simple explanations of conquest or appropriation. In America, Africa, and Australia, indigenous tribes fought over land before and after the first migrants arrived.

“[P]opulation movements were not caused by aboriginal people losing their own lands to white settlers, but by taking advantage of new technology [European guns] secured through trade,” Canadian historian Tom Flanagan noted in First Nations? Second Thoughts (2008).

The record shows land was seized by colonial authorities as retribution, in places such as Tasmania, South Africa, and New Zealand. Biggar challenges revisionist views that colonised tribes never intended their land to be alienated only to “share” it – ignorance of British ways was no defence, as tribes treated land conquest in the same manner.

Accusations of genocide are commonly applied to the past to label events from famines to cultural assimilation. Biggar argues for a tighter definition, saying all the claimed examples in the British Empire fell well short of practices in Nazi Germany, the Soviet Union, and Mao’s China.

An engraving by Granger, in 1857, of the rebellion of the Bengal Army.

Biggar finds it impossible to create a balance sheet that reflects the realities of colonisation. One list of the gains, provided by LG Reynolds in Economic Growth in the Third World: 1850-1980 (1985), would fill many pages, while the negative side of the ledger is usually summed up by violent conflicts.

Biggar examines six of these in depth: the First Opium War 1839-40; Indian Mutiny (1857); Amritsar massacre (1919); Benin invasion (1897); Second Anglo-Boer War (1899-1902); and the Mau Mau insurgency in Kenya (1950s). None of these rival the human carnage of the 20th century’s two World Wars, or indeed the death toll of many millions under post-colonial governments in China, Africa, and India.

Nevil Gibson is a former editor-at-large for NBR. He has contributed film and book reviews to various publications.

This is supplied content and not commissioned or paid for by NBR.

Sign up to get the latest stories and insights delivered to your inbox – free, every day.