Dreams and reality: The Arab world of two great men

Sir Ranulph Fiennes on TE Lawrence.

WATCH: NBR columnist Nevil Gibson speaks with Calida Stuart-Menteath.

Sir Ranulph Fiennes on TE Lawrence.

WATCH: NBR columnist Nevil Gibson speaks with Calida Stuart-Menteath.

History has long been rewritten to suit the intellectual trends of contemporary society. In some cases, it is little more than political propaganda. One recent phase has been to discredit the pillars of Western civilisation.

Other fads have fallen by the wayside because they have been superseded by greater knowledge or change. One is the ‘great man’ theory, which was popularised in the 19th century when the reach of European power extended to all parts of the world.

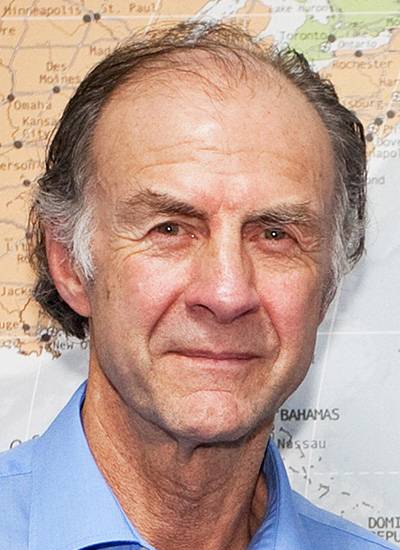

Sir Ranulph Fiennes.

Another was the religious ‘doctrine of discovery’, a 15th-century Catholic construct to justify territorial claims of lands previously unknown to the Europeans. Historian Paul Moon has debunked an anonymously written Human Rights Commission report, Maranga Mai, that falsely claims a relevance to New Zealand. Worse, it “manipulates and distorts the historical record”.

But tradition dies hard, and publishers are wise to factor it into their products. What could be better than a combination of two ‘great men’ famous for their expertise in discovery and exploration?

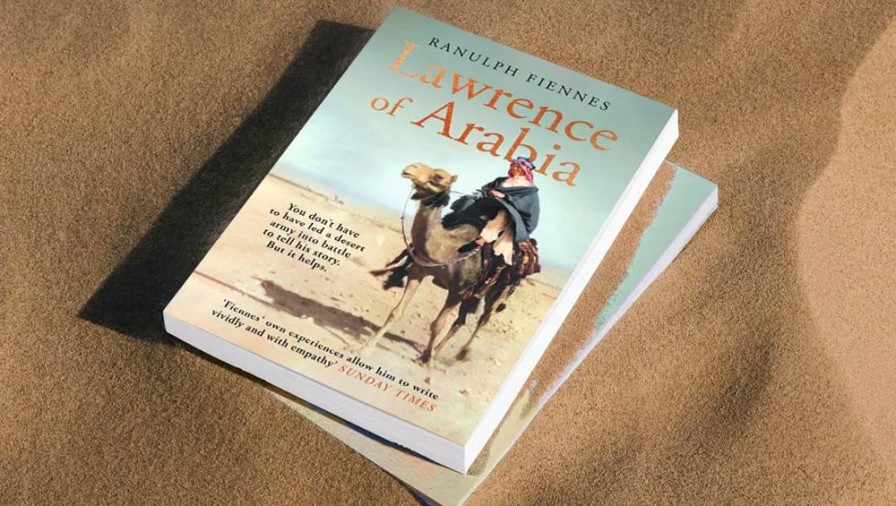

This is the case with Lawrence of Arabia, a biography by Sir Ranulph Fiennes, the greatest explorer of his time. Admittedly, Fiennes didn’t discover the world but he was famous for going where others hadn’t: crossing the Antarctic on foot and the only living person to have circumnavigated the globe by its poles.

His list of achievements goes on: after a heart attack and operation in 2003, he ran seven marathons on seven continents in seven days. In 2009, he successfully climbed Mt Everest on his third attempt.

When not testing his physical limits in feats of endurance, Fiennes wrote about them. He is the author of more than 30 books of fiction and non-fiction. They include biographies of two other Antarctic explorers, Shackleton and Scott, as well as advice on cardiac health, long-distance running, and a family history (his full surname is Twisleton-Wykeham-Fiennes and his aristocratic title is Third Baronet of Banbury).

It crossed more than one mind, including Fiennes’ owh, that this exemplar of the heroic British tradition had an earlier parallel in the life of TE (Thomas Edward) Lawrence, who was immortalised in his autobiography, Seven Pillars of Wisdom, and David Lean’s 1962 movie starring Peter O’Toole.

Peter O’Toole in the 1962 movie Lawrence of Arabia.

Fiennes says he always admired Lawrence as a “man without equal”, whose example “often inspired me to victory in life-or-death situations” and was his companion when facing “impossible military and political odds, as well as confronting personal scars”.

The book is unusual for a biography because the author interposes his own experiences and dilemmas with those of his subject.

“[Lawrence’s] adventures in the desert were enough to stir the blood, but the complexity of his character also held me in his grip,” Fiennes states.

Fiennes was first able to emulate his hero’s use of what is now called ‘guerilla warfare’ when posted as an officer to Oman in 1967, aged 24, to lead an Arab platoon against a Marxist insurgency known as the Dhofar Rebellion, backed by the Soviet Union and China. The communist powers were keen to fill the vacuum left by the British retreat from Aden.

Though Oman resisted falling victim to the insurgents, nearby Yemen was not so fortunate, as today’s headlines from the Middle East conflicts attest.

Lawrence was first attracted to the Middle East as an Oxford graduate in archaeology to diggings at Carchemish, north of Aleppo in modern Syria, from 1911-14 in his early 20s. He had already embedded his lifestyle into the Arab culture, where his ability to cure scorpion bites, cholera, and malaria gave the blue-eyed blond ‘miracle worker’ status.

This was valuable when he joined the British Army as an Arabic adviser in Egypt after the outbreak of World War I. Lawrence soon became the military leader of Arab tribes opposed to the Turkish-run Ottoman Empire, which was allied with Germany. The key Arab figure was Abdulla bin Hussein, the emir of Mecca who had a goal of ruling Syria, Hejaz (a Red Sea port), Mesopotamia, and Arabia. His rivals were Ibn Saud and Ibn Rashid.

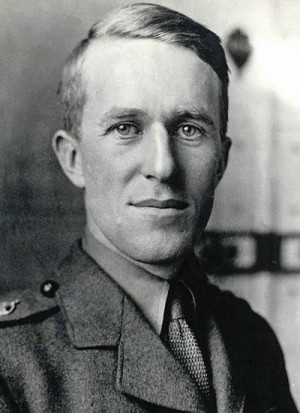

British Army file photo of TE Lawrence in 1918.

Lawrence was at first a reluctant commander, as he considered the Arab forces were undisciplined and would desert to fulfil tasks at harvest time or to feed their animals. He thought they were also untrustworthy and were bribed to fight only when they could loot villages or trains after conquering them.

Fiennes describes similar experiences in Oman, learning from Lawrence on how to use guerilla tactics against a superior-armed enemy. Lawrence’s campaigns against the Turks and Germans are described in detail, though Fiennes uses non-standard spellings for many places. While these military exploits helped the British cause, Lawrence’s main commitment was to Abdulla and, notably, one of his four sons, Feisal.

Britain and France had no intention of handing the Arabs any parts of the Ottoman Empire to fulfil their nationalist goals. The secret Sykes-Picot Agreement of 1916 had divvied up the Ottoman Empire long before victory, leaving only Arabia outside the control of the four European powers that eventually signed it (the others being Russia and Italy). Ibn Saud later gained most of Arabia.

Lawrence led the “long march” of the tribal warriors to seize Akaba (Aqaba), a heavily defended port that is now part of Jordan on the Gulf of Aqaba. This entitled him to join General Edmund Allenby on the December 1917 entry into liberated Jerusalem, which British Prime Minister David Lloyd George had promised to his people “by Christmas” after the failure to capture Gaza.

TE Lawrence in Damascus, Oct. 1918. Photo: The Rolls Royce Heritage Trust

At 28, Lawrence had been awarded the highest medal for bravery but failed in his goals for the Arabs. Damascus was to come under French control and the Arabs in the British mandate of Palestine weren’t consulted on decisions that eventually led to the Jewish state of Israel three decades later. Lawrence also suffered a personal tragedy when he was briefly captured and tortured by Turkish forces.

“Arab incompetence, the Allies’ duplicity, the Turkish sexual attack in Deraa [Syria], and the conflict within himself [had] become too much to bear,” is how Fiennes describes Lawrence’s fragile state of mind after Damascus fell and hostilities in the Middle east ceased on October 1, 1918.

But failure was soon to turn into celebrity status, as details of Lawrence’s daring desert campaigns were published in With Lawrence in Arabia (1919), by American journalist and photographer Lowell Thomas. However, Lawrence’s fame was not sufficient to help the Arab cause at the post-war Paris peace talks at Versailles.

Lawrence retreated to private life, joining the RAF under an assumed name until 1935, despite a further burst of world fame from publication of his memoir in 1926. The 250,000-word text was initially published in a private edition before the public edition at half that length. (An unabridged version was eventually produced for the public in 1997.)

High praise came from George Bernard Shaw, Winston Churchill, and EM Forster for what Fiennes calls a “new type of hero for the 20th century”. Apart from demonstrating his “extraordinary courage and bravery”, it also revealed a “complex character, laying bare his defects, his capacity for deceit and, most shockingly of all, the events of Deraa, where he admitted he had been sexually aroused”.

The Arab Commission to the Peace Conference in 1919. Emir Feisal in front. Lawrence second from right, second row.

The public, Fiennes observes, were ready for a “flawed hero” and, despite some detractors, his reputation was further burnished by military historian Sir Basil Liddell Hart’s authorised biography in 1934.

“The carnage of war, and the death of millions, had perhaps persuaded [the public] that conflict was not romantic and that the men who fought were often tragic figures who carried a heavy burden and battled on regardless,” Fiennes muses.

After Lawrence’s death in a motorcycle accident in 1935, his legend produced some 300 books. Fiennes differentiates his contribution by his own parallel experiences, without claiming heroic status for himself. However, he does express some doubts about his involvement in Oman.

He helped saved the sultanate from communism but witnessed the ruler keeping the oil revenues for himself, just like the African dictators in last week’s book column. But on his return to Oman in 1973, Fiennes’ conscience was salved by the old sultan’s overthrow by his more enlightened son, Qaboos bin Said, who abolished slavery and ensured the oil profits were more equitably shared.

Qaboos, who died in 2020 after a reign of 50 years, was at least one Arab leader who came close to close to Lawrence’s intentions in a part of the world that is noted more for its lack of leadership.

Lawrence of Arabia, by Ranulph Fiennes (Michael Joseph).

Nevil Gibson is a former editor at large for NBR. He has contributed film and book reviews to various publications.

This is supplied content and not paid for by NBR.

Sign up to get the latest stories and insights delivered to your inbox – free, every day.