Democrats vs dictators: The battle for AI’s future

‘Sapiens’ author paints big picture of contrasting futures.

Nexus: A brief history of information networks from the Stone Age to AI, by Yuval Noah Harari.

‘Sapiens’ author paints big picture of contrasting futures.

Nexus: A brief history of information networks from the Stone Age to AI, by Yuval Noah Harari.

Like many others from Generation Z, the new Māori monarch, Kuini Nga Wai Hono i te pō, has had some OE. In 2022, having met the then Prince Charles, she shared her thoughts of another monarchy with Re: News, part of TVNZ’s online news service.

“My heart was heavy when I arrived [in London] because I saw how vast and abundant the land is here,” she is reported to have said, “So why did they have to come to Aotearoa? To steal our land, to murder our ancestors and grandchildren? To confiscate our resources, and for what reason?”

It’s a question many historians have wrestled with in the context of the rise and fall of empires and civilisations. It was summed up by Israeli historian Yuval Noah Harari in his widely read Sapiens: A brief history of Humankind and repeated in his latest work, Nexus: A brief history of information systems from the Stone Age to AI.

Yuval Hoah Harari.

In recent times – say from the 15th century – Spanish, Portuguese, and Dutch conquistadors were building the first global empires. “They came with sailing ships, horses, and gunpowder,” Harari states. “When the British, Russians, and Japanese made their bids for hegemony in the 19th and 20th centuries, they relied on steamships, locomotives, and machine guns.”

These imperial conquests were possible because of powerful new technologies developed in Europe. Like most inventions, they created anxieties that they would invoke the apocalypse. The Luddites warned of doomsday scenarios from machines, while the English poet William Blake wrote of the Industrial Revolution’s “dark Satanic Mills”.

But these also produced the most affluent societies in history, enabling people today to live in far better living conditions than their ancestors in the 18th century. Harari doesn’t ignore the downsides. Unlike relatively self-sufficient agrarian societies, industrial ones depended on foreign markets and raw materials that only an empire could provide.

Imperialists claimed this was not just essential for their own survival but would also benefit the so-called undeveloped world.

“Millions of indigenous people saw their traditional way of life trampled under the wheels of these industrial armies,” Harari goes on. “It took more than a century of misery before most people realised that the industrial empires were a terrible idea and that there were better ways to build an industrial society and secure its necessary raw materials and markets.”

That is a brief answer to the question posed at the beginning. But Harari has moved on. He is now concerned with raising issues for the next stage in the world’s development: the role of information systems and how to ensure the mistakes of the Industrial Revolution are not repeated.

Like Sapiens, which is the go-to book for those wanting to know how the modern world came to be dominated by a single human species, Nexus bulges with facts and stories. The text runs to 400 pages, supplemented by nearly 100 more of sources and an index.

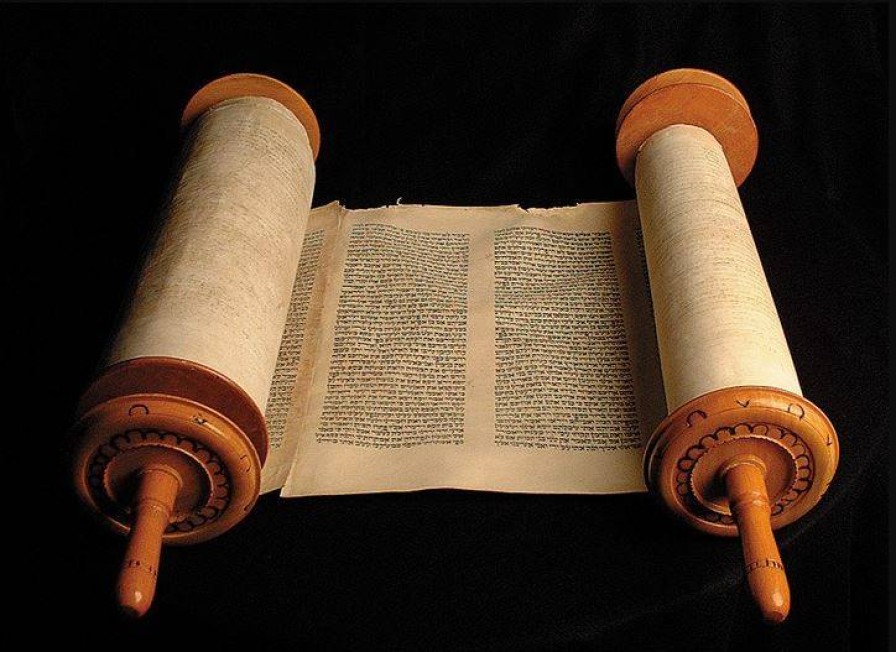

Early copies of the Bible were hand-made.

Homo sapiens succeeded because they could cooperate in large numbers due their ability to invent intangible things such as governments, laws, companies, money, and human rights through stories. This was possible because bits of information could be connected to a network that maintained social order.

These stories were converted into documents by a bureaucracy that exercised power over the many. A primary example was how the Christian Bible was compiled from dozens of documents, which gave the church the sole power to interpret them.

“All those interrelated texts didn’t represent reality; they created a new information sphere even bigger and more powerful than that created by the Jewish rabbis.”

A Swiss burning of three witches in 1585.

The church even controlled book production, making a perfect echo chamber for infallibility until the invention of the printing press in the mid-15th century. This was a major turning point, but it was a double-edged sword.

“… [P]rint allowed the rapid spread not only of scientific facts but also of religious fantasies, fake news, and conspiracy theories.”

For more than two centuries, beliefs in magic and a worldwide conspiracy of satanic witches led to the violent persecution of mainly women, who were blamed for all societies’ ills.

Harari cannot resist modern-day parallels with the internet and conspiracies about paedophile rings and the cancel culture.

The emergence of modern science, based on factual reality rather than myth, had a positive effect. It introduced the notion of fallibility, the discovery of ignorance, and the process of self-correction.

The latter is crucial to Harari’s contrasting accounts of how the information is treated in open and closed societies. Democratic societies, which began to emerge in the ancient city-states of Mesopotamia and Greece, enjoyed some credence before the growth of the Roman Empire. At its peak, it ruled over millions, limiting democratic systems to the local level.

But the autocrats lacked the modern mass media to enforce their control. However, these tools were available in the 20th century, where newspapers and radio were ruthlessly exploited in the totalitarian societies of the Soviet Union and Nazi Germany.

Stalin in 1937.

“The relentless barrage of fake news and conspiracy theories helped keep hundreds of millions of people in line,” Harari states, noting that Stalinism won intellectual admirers in the West due to the false belief that it was “the best shot at ending capitalist exploitation and creating a perfectly just society”.

Moving into the digital age, which takes up the second half of Nexus, Harari leaps from historical perspective to that of prophecy, as computers – through artificial intelligence (AI) – acquire the ability to create what he calls “inorganic networks”, that is, machine-made ones.

Here, his warnings become apocalyptic: computers will change minds rather than become violent robots: “They could manipulate human beings to pull the trigger.” And: “Computers can use their power to make decisions, create ideas, and deepfake intimacy in order to influence humans in ways that no document ever could.”

The main message of the historical part of Nexus is that information doesn’t equate to truth and that information systems don’t uncover it. The future will be about newly created political structures, economic models, and cultural norms.

Harari may overstate the degree of this “unprecedented” change, but he isn’t lacking in examples and scholarly backup. An early one was the role of Facebook in fomenting the demonisation of Myanmar’s Muslim Rohingya community in 2016/17. A progom was followed by the military seizing control of a fledgling democracy.

This sets off a series of other warnings gleaned from the work of other experts on the impact of the digital age on democracy. Harari lists a dozen or so books published this century. Most look too forbidding to the general reader; his summaries are a useful start for those who seek a deeper knowledge.

China is a world leader in facial recognition surveillance.

In his conclusions, Harari details the Chinese Communist Party’s large-scale use of digital power to embed its control over a billion-strong population, including sophisticated facial recognition techniques and “social credits” that rate citizens according to their positive or negative contributions.

(This was the subject of ‘Nosedive’, the first episode in season three of the Netflix TV series Black Mirror. If you want to see the scale of existing surveillance, check out The Lie, a British-made Netflix documentary on the murder of Grace Millane in Auckland in 2018.)

China set a goal in 2017 of becoming the world’s primary AI innovation centre. Russia has made a similar declaration. This is the perverse side of AI as a tool for authoritarian dictatorships.

In the West, AI innovation is largely left to private enterprise, hence the dominance of Meta (Facebook) and Alphabet (Google) in the social media. While Harari can hardly be called an optimist, he proffers solutions based on his Sapiens theory of cooperation that could lead to agreement on a common framework for thought and action.

This has a basis in nature, where species often have a symbiotic relationship with each other. In the past, human cooperation was expressed through trade and globalism. The obverse, a destructive pursuit of power through conflict, is a diminishing feature. Free societies spend much more on health and education than they do on military equipment.

Several experts took strong issue with the themes and facts in Sapiens, some of which are recycled in Nexus. It’s too early to assess whether it, too, will be a bestseller. It tackles a far more speculative area, but its sceptical analysis of AI, or “Alien Intelligence.” as Harari sometimes puts it, should have strong appeal.

Nexus: A brief history of information networks from the Stone Age to AI, by Yuval Noah Harari (Fern Press/Penguin Random House).

Nevil Gibson is a former editor at large for NBR. He has contributed film and book reviews to various publications.

This is supplied content and not commissioned or paid for by NBR.