Crete encounters: A generation learns the realities of war

Two novelists describe a battle that forged this nation’s identity.

WATCH: NBR columnist Nevil Gibson speaks with Maria Slade.

Two novelists describe a battle that forged this nation’s identity.

WATCH: NBR columnist Nevil Gibson speaks with Maria Slade.

In the histories of World War II, the Battle of Crete is remembered for several firsts. “Tired and ill-equipped” Allied troops had been pushed out of mainland Greece in early 1941, pursued by German forces that were expected to invade Crete by a sea and air, writes Matthew Wright in Those Who Have the Courage, his new official history of the New Zealand Armoured Corps.

The mass attack using paratroopers, known as Fallschirmjäger, was the first mainly airborne attack in military history. Another first was the Allied use of intelligence from encrypted German messages from the Enigma machine. Third, the civilian population of Crete, in conjunction with the Allied forces, was the first to put up mass resistance to German occupation.

The resulting German losses were so heavy that Hitler was reluctant to authorise further large-scale airborne operations.

Wright’s overall description draws parallels with the retreat from Gallipoli, with both operations involving Sir Winston Churchill and his belief, in both world wars, that Greece and the Balkans were the ‘soft underbelly’ of German or Axis controlled Europe.

Churchill wanted the Allies – British, Australian, and New Zealand forces – to support Greek neutrality. This was agreed despite misgivings from political leaders in Australia and New Zealand that such a campaign was futile based on available resources and German superiority.

Prime Minister Peter Fraser, according to Wright, described the task as “formidable and hazardous”. He was correct. In March 1941, Serbs in Yugoslavia overthrew a short-lived Croat-dominated government that had joined the Axis powers of Germany and Italy.

In the following month, Hitler ordered a two-pronged attack against Yugoslavia and Greece that within weeks had conquered all but Crete. “The Greek campaign had been a disaster as everybody except Churchill and his inner circle expected,” Wright observes. The troops who made it to Crete had no vehicles or heavy equipment.

German Fallschirmjäger (paratroopers) landing on Crete, May 1941.

While the British Navy held the upper hand at sea, later repulsing a seaborne invasion, Germany’s Luftwaffe had established superiority in the air. Bombing raids prevented the arrival of significant support in Allied troops and hardware from Egypt. It was also impossible to evacuate all the unwanted personnel on Crete who had no weapons or could not contribute to the defence.

The anticipated invasion began on May 20 with the mass attack of paratroopers aimed at seizing the Maleme airfield in western Crete held by three New Zealand battalions. Other parts of the island were controlled by Greek, British, and Australian troops.

The events that followed are the stuff of legend in the David and Goliath tradition. The overwhelming German forces suffered heavy casualties in rare examples in modern warfare of hand-to-hand combat.

While war histories such as Wright’s provide the broad details and occasionally quote from diaries of participants, it’s novelists who must provide the human and emotional context.

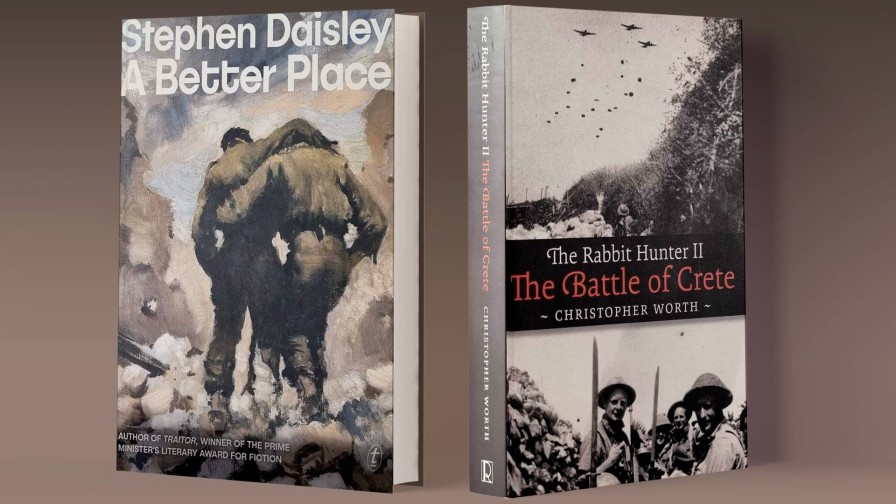

Two recent examples use the experience of New Zealanders in the Battle of Crete. Christopher Worth’s The Battle of Crete is the second in a planned trilogy, The Rabbit Hunter. The first part was reviewed in this column in March 2023. It traced a fictional hero, Second Lieutenant Neil Rankin, and his unit during the retreat from mainland Greece.

Christopher Worth.

Worth, a retired Dunedin accountant, makes no literary pretensions but his writing has improved from clunky and often clichéd dialogue and description to vivid action scenes and effective use of detail. These were first demonstrated in his account of the fire fight at the Corinth canal bridge in The Rabbit Hunter I.

The move to Crete, where the action is much more intensive and gruesome, extends the book to more than 450 pages as Rankin is involved in 22 Battalion’s attempt to regain control of the Maleme airfield. Worth uses fictional characters up to the rank of captain, presumably because their constant grumbling and criticism reflects a belief in the veracity of the ordinary soldier rather than their superior officers.

But Worth uses real names for those in command, with brief biographical footnotes. For example, intelligence officer Dan Davin is cited as basing his defensive plans on a German seaborne invasion that never happened. Davin later wrote the official history of the Crete campaign (1953), spending much of his career at the Oxford University Press. He also wrote nine books of fiction and a literary memoir. OUP published a biography by Keith Ovenden in 1996.

Davin is also referenced negatively in Stephen Daisley’s A Better Place, a widely acclaimed novel and the only one by a man to make the finalists in this year’s biggest literary award, the Jann Medlicott Acorn Prize for Fiction worth $65,000. Daisley was an Acorn winner in the Ockham Book Awards for Coming Rain in 2015 and the Australian Prime Minister’s Literary Award for his first novel, Traitor (2011).

Daisley, who was born in Hastings, is a serious literary talent but not as well known here as he should be because lives in Perth. A Better Place is not all about Crete but the fixed bayonets combat around Maleme airfield provides a key turning point in the story of twin brothers, Roy and Tony Mitchell.

Stephen Daisley

Their backgrounds will be familiar to early Baby Boomers, whose parents were defined by their wartime experiences. Roy and Tony grew up in the harsh rural hinterland of Taranaki on a ‘development’ farm reminiscent of Maurice Shadbolt’s Strangers and Journeys.

Effectively orphaned by their father’s abusive alcoholism and abandonment by their mother, they sign up for war service in their late teens and, contrary to policy, are together in the combat zone when the Fallschirmjäger arrive. Roy is forced to leave an injured Tony behind on the battlefield, a decision that haunts him throughout the rest of his service in North Africa and Italy.

On his return home, like his father from World War I, he is given two pieces of undeveloped land where he ekes out a lonely existence based on his survival instincts. Meanwhile, only the reader is aware that Peter, an amputee, survives as a prisoner of war in Silesia where he discovers his talent for painting.

Daisley writes terse, taut prose, often reducing sentences to one word. Dialogue is honed to its bare bones while description and background is kept to a minimum. Political perspectives are restrained, echoing those of the rural working class in the days before wool-boom prosperity made life comfortable.

As much is understated, you are left with Daisley’s modern sensibility about a generation who faced trauma without the awareness of today’s mental health issues.

The lasting memory from both books is that battlefield in Crete where war was no abstraction. While Worth does the hard yards in his on the ground descriptions and depth of research, Daisley’s stripped-down version leaves you wanting more.

Note: A full review of Those Who Have the Courage will be in a future column.

A Better Place, by Stephen Daisley (Text Publishing).

The Battle of Crete (The Rabbit Hunter II), by Christopher Worth (Renaissance Publishing).

Nevil Gibson is a former editor at large for NBR. He has contributed film and book reviews to various publications.

This is supplied content and not paid for by NBR.

Sign up to get the latest stories and insights delivered to your inbox – free, every day.