Cosmic journeys: Moon is just the beginning

Experts explore the impact of Earth’s great power rivalries on space.

NBR columnist Nevil Gibson speaks with Calida Stuart-Menteath.

Experts explore the impact of Earth’s great power rivalries on space.

NBR columnist Nevil Gibson speaks with Calida Stuart-Menteath.

Global tensions have never been higher since the Cold War, we are told, thanks to Chinese balloon espionage, aerial dogfights off the Korean coast and, of course, the Russia-Ukraine war.

The US spent hundreds of thousands of dollars firing rockets at the balloon and other unidentified objects in low-Earth orbit, prompting the White House to deny suggestions of an alien invasion.

Secretary of State Antony Blinken said the balloon’s entry in the US airspace was ‘irresponsible’ while a top Chinese official called the response ‘hysterical’. Blinken also said information that China was considering lethal weapons aid to Russia could cause “a serious problem”. China also said it would hold naval exercises with Russian and South African navies.

On the sidelines, North Korea fired an intercontinental ballistic missile that landed off Hokkaido in Japan as the US, South Korea and Japan held aerial drills; the Pentagon’s top China official went to Taiwan – the first known trip since 2019; and Iran was said to have uranium enriched to the levels just below what’s needed for a nuclear weapon.

Finally, the American and European space agencies revealed at a Royal Society astronomical conference in London that they would follow China’s lead in establishing a radio telescope on the dark of the moon, which is sheltered from Earth’s own transmissions. It is believed this is the best place to track signals from the universe, possibly signifying the existence of intelligent life forms in the cosmos.

Space, like Earth, has gone full circle from an era of Cold War competition, primarily between the US and Russia, to cooperation in the form of the International Space Station and, more recently, back to a potentially deadly form of rivalry as nation states go their own ways.

Some of this is purely scientific but multinational collaborations are also forming along lines that split the earthly powers into the democratically aligned nations and those with authoritarian or ideological foundations.

Aboard the International Space Station.

An excellent beginner’s guide to recent developments in space is the latest in a series of magazine-style compendiums from Italian publisher Europa Editions under the catch-all title of The Passenger. It offers long-form essays, investigative journalism, and visual narratives in book form. Until now, the series has focused on countries or territories (Ireland, California) or cities (Berlin, Rome).

The Passenger: Space comprises six main essays supplemented by dozens of text boxes and illustrations. Two of the most substantial are excerpted from books that non-specialist readers may have overlooked or not found available in English: Jo Merchant’s The Human Cosmos (2020) and Dutch writer Frank Westerman’s Die komische komedie (2021), which is translated as ‘Cosmic Comedy’. Others are commissioned or have appeared in magazines.

Merchant’s field is astrobiology: the study of space debris, meteorites, and the like to discover whether life on Earth is matched by an extra-terrestrial existence. It’s a field where knowledge moves fast, and many readers may find notions learned years ago are seriously wrong.

Artist’s impression of possible Sino-Russian moonbase.

One concerns a fragment found in the Antarctic in 1984 but remained a mystery until it was found recently to be from Mars. It showed signs water had existed there, although today it’s a planet that no longer has a magnetic field or an atmosphere to protect it from the sun’s harsh radiation.

The moon is only three days’ rocket flight away, which makes it ideal as a refuelling stop or launching pad for sending spaceships deep into the cosmos; the costliest part of propulsion is the energy required to leave Earth.

While the existence of extra-terrestrial life forms hasn’t been proved, Merchant says the likelihood is high, with an estimated 8.8 billion planets like Earth orbiting stars throughout the universe. “Now we’re confronted with a diversity of planets beyond anything we could have imagined – a universe with more planets than stars,” she writes.

Given the evidence from Mars and the extremities under which life forms can exist on Earth, their existence elsewhere in the cosmos is more likely the rule rather than the exception. The only question is finding them.

China’s SETI (Search for extra-terrestrial intelligence) telescope in Guizhou.

China has gone the extra mile by building the world's largest radio telescope in a remote mountainous area of the south-western Guizhou province. Ross Anderson, deputy editor of The Atlantic, visited it in 2017 and his account is republished here.

He quotes from leading Chinese sci-fi writer and ‘first contact’ guru Liu Cixin, author of The Wandering Earth, about the dangers of alerting the cosmos to your existence, as opposed to listening for any signals.

The Wandering Earth, which has been made into two movies, is evidence of China’s long history of astronomy and among the latest production’s conceptual features is a representation of a space elevator leading to a station above the atmosphere.

This was first conceived by Konstantin Tsiolkovsky, Russia’s patriarch of space travel, in his 1893 novel On the Moon. Hollywood, too, has made some serious attempts at first contact, including Contact (1997), based on Carl Sagan’s research, and Arrival (2016).

Anderson questions whether China, under its secretive authoritarian rule, can be trusted with making the ‘first contact’. Hence the move to follow the Chinese to the dark side of the moon.

The Vostochny Cosmodrome in Russia’s far east.

Westerman’s essay is based on a visit to the Soviet-era cosmodrome at Baikonur, in Kazakhstan, and since replaced by Vostochny, in Russia’s far east. He also describes how two of the Voyager probes into outer space took with them vinyl discs, called the Golden Records, presenting a positive spin of cultural life on Earth several decades ago for any civilisation with a phonograph.

The moon was also the subject of Rivka Galchen’s exhaustive article from The New Yorker in 2019. The reactivation of lunar exploration is already well under way, with the successful first stage of the Artemis project being completed last November, with the Orion rocket’s flight around the moon and back.

New Zealand and many other countries have signed up to Artemis, which Jack Burns, the head of NESS (Network for Exploration and Space Science), compares with the government assistance given to the aviation industry in its infancy during the 1920s.

But the American space agency Nasa is unlike those of China and Russia, where the state is both the funder and provider of such missions. To get more bang for its buck, Nasa outsources its delivery rockets and much else to the private sector, which is expected to make space travel commercially viable sometime in the future.

This is largely due to Nasa’s limited budget of US$21.5 billion compared with the US Department of Defence’s annual spend of US$700b. Galchen raises the possibility that a moonbase would be better suited to robots than humans, given its lack of atmosphere and magnetic force. It could become a source of cheap manufacturing without fears that exploiting the moon’s resources has negative parallels with Earth’s history.

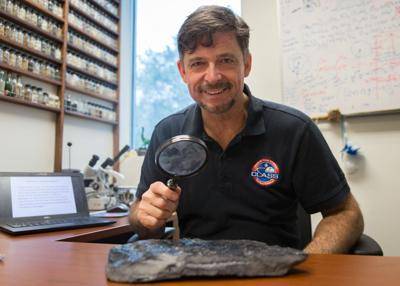

Professor Philip Metzger is developing ways to mine water on the moon.

For a start, the seizing of land would not be an act of colonisation against an indigenous people. Philip Metzger, a professor at the University of Central Florida, puts it this way:

“The resources in space are billions of times greater than on Earth. Space pretty much erases everything we do. If you crush an asteroid to death to dust, the solar winds will blow it away. We can’t really mess up the solar system.”

Icelandic author Andri Snaer Magnas takes the contrary view of Earth as an asteroid with limited resources that are being exhausted.

The collection includes two first-hand accounts: a family trip to the Kennedy Space Centre Visitor Complex at Cape Canaveral by sceptical novelist and mother Lauren Goff (Fates and Furies, 2015); and Paolo Giordano’s guided tour of the Gran Sasso Laboratories, the world’s largest underground research centre at L’Aquila in central Italy. It is built in hard rock to eliminate all forms of radiation for study of particle physics and the origins of the cosmos.

Australian writer Elmo Keep provides an entertaining finale with the story of a scam promotion called Mars One, in which volunteers were literally promised a one-way journey of a lifetime after 10 years’ training.

The Dutch promoters’ claims are systematically debunked by Keep’s fact-checking, which sets out the practical realities of such a mission. But as Mars is just six to eight months’ travel from Earth using the latest rockets, its eventual ‘colonisation’ seems inevitable.

The Passenger: Space, English edition edited by Simon Smith (Europa Editions).

Nevil Gibson is a former editor at large for NBR. He has contributed film and book reviews to various publications.

This is supplied content and not paid for by NBR.

Sign up to get the latest stories and insights delivered to your inbox – free, every day.