China Interrupted: Path to world domination gets rockier

Archival historian examines Chinese Communist Party’s record in practice.

NBR columnist Nevil Gibson speaks with Fiona Rotherham.

Archival historian examines Chinese Communist Party’s record in practice.

NBR columnist Nevil Gibson speaks with Fiona Rotherham.

Two years of a global pandemic and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine have sidelined China’s ambitions to supplant the world’s superpower and its allies in Asia and Europe.

The irony is that China nurtured the latest coronavirus to sweep around the world, largely because of an initial cover-up and refusal to work with the UN’s health agency. This response was no different from the outbreak of an earlier virus, SARS, in 2002.

It revealed a deep-seated pattern of control that has stamped the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) since it seized power in 1949. It is based on history of broken promises outlined in Mao’s 1940 “new democracy” manifesto.

On taking power, the CCP eliminated all civil organisations, unions, and business associations that threatened communist ideology. In 1950, all non-socialist books were burned. In 1956, all forms of commerce and industry, including small shops, were brought under state control. In 1958, all agricultural land was collectivised, ending any property rights.

The human cost was horrific and comparable with the tens of millions who died in the purges under Stalin. Public executions continued well into the 1980s.

Professor Frank Dikötter.

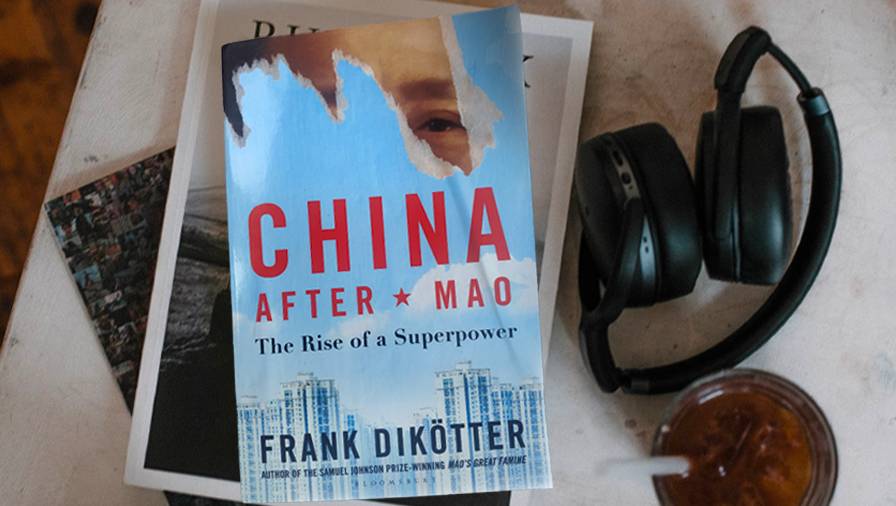

These events have been recorded in detail by Dutch-born, Hong Kong-based Professor Frank Dikötter in a series of books based on archival records. His latest, China After Mao, covers the period from 1976 to 2012.

A brief epilogue gives an update on the personality cult of Xi Jinping, the suppression of Hong Kong, the pandemic lockdown, the frantic growth in military power, and the pervasive system of surveillance and censorship that has seen most foreign correspondents banned.

China’s rise as a world power is a remarkable arc. But it is now at a turning point. Its status has been sacrificed in a loss of confidence by all but a handful of admirers. Many of the projects in the trillion-dollar Belt and Road Initiative have ground to a halt; borrowers such as Sri Lanka, Zambia and Pakistan have become failed states under China's "debt-trap diplomacy." Western economists have estimated 60% of Chinese overseas loans are held by countries that cannot repay them.

China has border disputes with 14 of its neighbouring countries, not to mention Taiwan, and boasts among its few friends the brutal military dictatorship of Myanmar, the despotic theocracy of Iran, and the aid-dependent, tribally riven Solomon Islands.

Dikötter says of China’s relationship with the US: “The regime had succeeded in alienating … the one power that had created the very conditions on which it had depended for its survival.” This reached its peak under the “going global” period after the financial crisis of 2008-9.

That has since been followed by the withdrawal of Western and Asian businesses from China, and its retreating ‘soft power’ as universities close Confucius Institutes, which once numbered 280 in 80 countries.

Tiananmen Square demonstration in 1989.

Dikötter’s forensic work gives plenty of examples where China was given the benefit of the doubt after the 1989 massacre in Tiananmen Square. The evidence now points to that goodwill having dissipated, particularly since China closed itself to the outside world since the Covid-19 pandemic.

One outcome is the realisation of the CCP’s duplicitous intentions, though Dikötter says these have never been hidden; they were merely ignored by those who stood to gain from China’s economic power.

His archive-based research also provided the base for his trilogy – The Tragedy of Liberation, Mao’s Great Famine, and The Cultural Revolution. This includes the secret minutes of top party meetings, investigations into cases of mass murder, confessions of leaders responsible for the starvation of villagers, and reports on resistance in the countryside. Other records are confidential opinion surveys, letters of complaint from ordinary people, and economic data that have not been made public.

But in November 2012, when Xi first emerged as an unchallenged dictator, the archives started closing again and, in the case of the Maoist period, were reclassified. Paradoxically, Dikötter reports the past two years have been favourable to examining the period of “reform and opening up” that is covered in China After Mao.

The research reveals unpleasant facts that run counter to those who believed the Chinese economic ‘miracle’ would result in it becoming more democratic, a stakeholder in the global trading system, and a positive contributor to the world community.

Dikötter reveals this was a myth all along. At no point was the CCP going to separate political and economic power.

“On the contrary, maintaining a monopoly has repeatedly been defined as the overwhelming goal of economic reform,” he writes. In fact, prosperity for the middle class has enabled the state to “reduce the scope for liberalisation further and further,” to quote Premier Zhao Ziyang in 1987.

Xi Jinping has tightened his grip on China.

Xi’s tightening grip on power is further evidence. So is the fact that capitalism in the Western sense does not exist. China is still committed to five-year plans and private companies are restricted to CCP members.

Capitalism requires capital, and that is not controlled by individuals but by state-owned banks that distribute it to “enterprises controlled directly or indirectly by the state in pursuit of political powers”.

In other words, without political reform, economic reform cannot exist. “The argument over whether trade can or should be ‘free’ misses the key point, namely that a market without the rule of law, backed up by an independent judicial system and a free and open press, is not much of a market at all.”

At the World Economic Forum, at the height of the GFC, Premier Wen Jiabao denounced Western capitalism as unsustainable in its “blind pursuit of profit” and failure to supervise its banks. Wen’s family was noted for its accumulation of wealth, detailed in Desmond Shum’s insider account, Red Roulette.

China has opened up in the 33 years since the Tiananmen massacre compared with the prior 40 years but, in Dikötter’s view, this barely compares with Western economies.

“What the regime has built … is a fairly insulated system capable of fencing off the country from the rest of the world.” Since 1976, the archives reveal China has created “countless rules, regulations, sanctions, bonuses, deductions, subsidies, and incentives … [that] may be the most unlevel playing field in modern history.”

Between 1976 and 2001, China’s per capita income fell to 130th from 123rd in World Bank rankings. The household share of the economy was among the lowest in the world. Growth at all costs in the new millennium changed that but at a high price. The cost of imported raw materials for manufactured products exceeded their sale price.

The world’s consumers benefitted from the cheap, subsidised exports, often made by subsidiaries of global companies. They had closed their factories in the advanced economies because they could not compete. By 2005, 90% of all goods made in China were in chronic oversupply.

Side effects included the worst pollution in the world and the outpouring of counterfeited, pirated, and unsafe goods. The 2004 baby formula scandal involving Fonterra was one of dozens of examples.

The destruction of capital was equally costly, much of coming from overseas. Data quoted by Dikötter showed that, for every three yuan lent by the state-controlled banks in 2000 to the largest 500 enterprises, they produced only two yuan in value.

The system could only exist by debt expanding faster than economic growth. As one Chinese economist put it: “Basically, China’s economy is all built on speculation and everything is overleveraged.” A giant Ponzi scheme, if you like.

This is propped up by state control of all the country’s assets, with CCP members controlling that wealth to their own advantage. Some 600 million – half the population – still live on just US$140 ($245) a month. What little savings they have are put in the banks that finance the building of skyscrapers, bullet trains, airports, and motorways.

This spending has little accountability and is squandered on a massive scale to create a mountain of debt that is equally opaque. The archives, Dikötter insists, show a disturbing level of ignorance about the figures underlying this system.

Obfuscation exists at every level of the hierarchy, with fabricated contracts, false customers, fake sales, and rampant accounting fraud.

It is a country run by a party that has no clear vision of the future.

“China resembles a tanker that looks impressively shipshape from a distance, with the captain and his lieutenants standing proudly on the bridge, while below decks sailors are desperately pumping water and plugging holes to keep the vessel afloat.”

It depicts a society with no grand or secret plan. Only one that creates a great many unpredictable events, unforeseen consequences, abrupt changes of course and a continuing power struggle behind the scenes.

China After Mao: The rise of a superpower, by Frank Dikötter (Bloomsbury).

Nevil Gibson is a former editor at large for NBR. He has contributed film and book reviews to various publications.

This is supplied content and not paid for by NBR.

Sign up to get the latest stories and insights delivered to your inbox – free, every day.