Masters of chaos: Profiting from disasters

ANALYSIS: The stories behind Wall Street’s ‘storm chasers’.

NBR columnist Nevil Gibson speaks with Calida Stuart-Menteath.

ANALYSIS: The stories behind Wall Street’s ‘storm chasers’.

NBR columnist Nevil Gibson speaks with Calida Stuart-Menteath.

Wall Street has discovered another sugar rush, just as most economists share a gloomy outlook as the world starts to pay back the debts of the Covid-19 pandemic.

A year ago – amid a bear market that left investors with losses from both their stock and bond portfolios for the first time in nearly half a century – only a handful of actively managed funds posted gains.

Fast forward to the end of June, and most funds made double-digit gains; the average was 15.6%. Only a handful of well over 1000 funds registered declines – thanks due to artificial intelligence (AI) stocks and other high-tech names.

Chip maker Nvidia posted a nearly threefold gain in its share price in the past 12 months. A year ago, it was easily the worst performer. But when OpenAI unveiled its chatbot in November, it set off a gold rush.

Such disruptions are not uncommon on Wall Street. They keep several high-profile writers busy looking behind the scenes for niches to explore.

The leader, at least in number of books, is Michael Lewis, 62, with Liar’s Poker (1989), The Big Short (2010), and Flash Boys (2014), among others. Lewis, a former bond trader, tells his Wall Street-based stories through personalities whose intellects make them leaders of the pack.

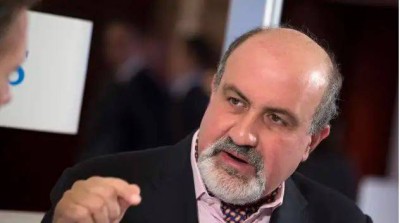

Scott Patterson, author of Chaos Kings.

William D Cohan, 63, is another who has used his experience as a mergers and acquisitions banker to produce six densely packed titles, including The Last Tycoons (2007), House of Cards (2009, not to be confused with the Netflix political series), Money and Power (2011), and Power Failure (2022). He was also the first to expose the scandals at media giant Viacom in an article for Vanity Fair, where Lewis is also a contributing editor.

Scott Patterson, 53, a fulltime reporter at the Wall Street Journal, has two heavyweight titles under his belt: The Quants (2010), about four mathematic savants who made billions out of formulas and high-speed computers only to lose it in the global financial crisis of 2008; and Dark Pools (2012), about the automated robotic traders and secretive exchanges.

Patterson’s latest, Chaos Kings, focuses on ‘crisis hunters’ or ‘storm chasers’, who profit only when markets crash. Again, he selects half a dozen or so of these super-intelligent investors who have turned this trading strategy into an art.

The best-known is Nassim Nicholas Taleb, 62, who provides the main thread of the book through his involvement with Mark Spitznagel in Empirica Capital and Universa Investments, two hedge funds aimed at protecting capital from major market falls or volatility.

Taleb had already challenged prevailing theories on Wall Street with Fooled by Randomness (2001), while Empirica, launched after the 1987 sharemarket crash, failed when markets rallied for two decades.

Nassim Nicholas Taleb, author of The Black Swan.

But their fortunes changed dramatically with the publication of Taleb’s The Black Swan, about unpredictable events, and the relaunch of a new ‘black swan’ fund, Universa, in 2007 just ahead of the GFC.

Apart from Taleb’s ideas, Spitznagel admired the Austrian school of economics and its boom-bust cycles of “creative destruction”. He had learned his craft as “street savvy” trader on Chicago’s futures exchanges. He was quick to spot any weaknesses.

Universa’s investors were told they would make incremental losses – a form of insurance – as they awaited the payoff day when markets nosedived, which they did in 2008 and again in 2015-16. The losses were purchases of cheap out-of-the-money put options that usually expired.

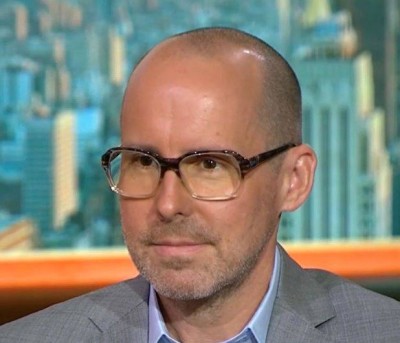

Mark Spitznagel, founder of Universa’s black swan fund.

Pension funds began to take notice of this contrarian strategy. One, the big California-based CalPERS, invested in 2017 but, after a management change, quit in 2020 just before Covid-19 struck. By contrast, Spitznagel correctly predicted governments and central banks would over-react to the Covid lockdowns and make things worse. They flooded the market with liquidity and slashed interest rates.

Volatility exploded, sending hedge funds to the wall, with CalPERS losing US$2b to US$3 billion. The new manager, who had quit the Universa fund, lost his job. (Which is more than you can say for the Reserve Bank managers who lost $10b of New Zealand taxpayers’ money without any consequences.)

As Spitznagel explained to Cohan in a Vanity Fair article: “By providing explosive downside protection for his investors, they could ‘take more systemic risk’ by being fully invested in stocks rather than putting a big chunk of cash into standard risk-mitigation assets like [US] Treasury bonds.”

In sheer numbers, Universa made US$3b in profit on a bet of just US$50 million in options. Spitznagel rubbished the diversification of Modern Portfolio Theory as any protection in a market rout. It was calculated that Universa’s investment of just 3% in a back swan fund, with the rest in the S&P500 stock index fund, could make compound returns 2% better than other strategies over a decade. At last count, Universa was the 24th largest fund in the US with US$20b under management.

Others colourful types rated as Chaos Kings include:

Didier Sornette.

This spread of ideas – based on arcane physics and mathematics as well as hunches about human behaviour – are just a taste of Patterson’s rich account. Those interested only in detail that is relevant to finance may reject some of his political packaging, which leans to the left, but it’s an excellent introduction to some of the other more technical books listed above.

Chaos Kings: How Wall Street traders make billions in the new age of crisis, by Scott Patterson (Scribe).

Nevil Gibson is a former editor at large for NBR. He has contributed film and book reviews to various publications.

This is supplied content and not commissioned or paid for by NBR.

Sign up to get the latest stories and insights delivered to your inbox – free, every day.