Blokes, bullets, broads: What happened to novels for men?

OPINION: Decline in readership of fiction is limiting the male experience.

NBR columnist Nevil Gibson speaks with Fiona Rotherham

OPINION: Decline in readership of fiction is limiting the male experience.

NBR columnist Nevil Gibson speaks with Fiona Rotherham

The Ockham New Zealand Book Awards are not a major concern for this column. Reviews are seldom the result of unsolicited books sent by publishers, and the industry’s dynamics have radically changed in recent years.

In fiction, the short list reflects international publishing trends with some local exceptions. Few new male authors are being published. In the UK, a search of the Bookseller trade paper showed only seven of the 77 debut novels in 2022 were by men.

In the latest Man Booker Prize longlist of 15 novels, eight female authors outnumber the five by males. One commentator noted: “A glance at the bestselling fiction list on Amazon reveals that around 80% of the fiction books featured in the top 25 on any given week have usually been written by women.”

When I looked, only a handful of genre writers featured. It was the same when I checked out displays in Whitcoulls. Crime and thrillers are still popular but they are unlikely to rank alongside Salman Rushdie in any awards list.

Furthermore, the publishing industry is no longer male-dominant. The 2021 Report on Diversity, Inclusion and Belonging by the UK Publishers Association shows women outnumber men by two to one and have done since the first report in 2015.

This is where the Ockham judges have changed tack in a bid, presumably, to stem accusations of feminisation. Some say it is dumbing down at the expense of literary fiction.

The fiction short list for the rich Jann Medlicott Acorn Prize is evenly divided by sex. But the men’s contribution is a thriller, Michael Bennett’s Better the Blood, and Monty Soutar’s bestselling Kawai: For Such a Time as This, a historical novel. One of the women has also authored historical fiction, Cristina Sanders’s Mrs Jewell and the Wreck of the General Grant, while Catherine Chidgey’s The Axeman’s Carnival is a more traditional highbrow novel.

Is it a problem that men aren’t buying serious fiction, and is it because the industry is biased against young male writers? Should the educational sector be concerned that half the population no longer consumes these books? Is it systemic failure, diminishing attention spans, or lack of suitable product?

Educators and parents may need to pay some attention to research showing reasons for this decline. A Financial Times columnist quoted studies that show only 20% of men read fiction, while 64% of novels are bought by women.

The author appeals to FT readers to consider the advantages of reading a novel over non-fiction.

“In a history book, a narrative is imposed on a messy jumble of events; stories are told as if they progress tidily and even rationally. This isn’t a criticism; it’s just the nature of the medium. With a novel, however, there is no such imposition: the thing itself is the narrative; there is no alternative version of the truth.

Financial Times columnist Jemima Kelly.

“A novelist is like a magician: although they are writing fiction, they have a certain authenticity about them, because we understand we are reading something that’s not real. And, as Aristotle suggests, it is this that allows the characters in a novel to somehow feel more real to us than historical figures; each represents a kind of embodiment of the human condition that we can relate to.”

She – Jemima Kelly – goes on to point out that increased empathy and emotional intelligence is more likely to be found in serious literature than popular fiction.

“This is because the reader is exposed to a much broader range of experiences and cultures than they would come across in real life, which helps them understand that other people have beliefs, desires, and perspectives that differ, sometimes greatly, from their own.”

This boils down to understanding complexity in both people and circumstances. As one psychologist, Nick Buttrick, psychology professor at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, told Kelly:

“Encountering difference, encountering different minds, encountering different sorts of sociality helps to scaffold this belief in the complexity of the world. If you’ve only ever encountered one sort of mind … and if you’re only reading … things which are predictable, safe, stable, people end up with a view of the world that is uncomplex, because that’s what you get repeatedly reinforced with.”

I tried to apply these sentiments to my own reading. Make no mistake, this is hard work. The new Salman Rushdie (Victory City) runs to a modest (for him) 350 pages. However, John Irving’s The Last Chairlift is a whopping 889 pages.

So, I turned to a pile of new first novels by middle-aged New Zealand males, who have turned to self-publishing. These are the result of much effort, some have taken writing classes, and been assisted with editing, production, and design.

None is likely to make a bestseller list. This will be due to the lack of a commercial publisher’s network and a reviewer’s column to publicise their existence.

Christopher Worth.

I chose Christopher Worth’s The Rabbit Hunter on the grounds that it involved characters that included South Island farmers who fought in World War II. It is written by a baby-boomer son of that generation; one who has not been in any conflict but has lived a full life as a professional accountant.

In other words, someone like myself – and the most likely target buyer. The title refers to the same occupation as my father’s before he became a soldier. Coincidentally, one of the characters has the same surname as mine and shows his prowess as a stalker of prey. In another coincidence, Worth’s mother was a Plunket nurse born in South Canterbury, as was mine.

But that is getting ahead of the story. Worth’s profession took him from his home in Dunedin to London, then to Christchurch and back to his hometown in 1987. He spent seven years in Moscow as a partner in the then Coopers & Lybrand from 1996-2002, which were the late Yeltsin years and saw the emergence of Vladimir Putin.

However, this interesting period is not the subject of The Rabbit Hunter, which covers a month in 1941 that is described in the Teach Yourself History of World II.

“Greece, which the Germans also invaded on April 6, didn’t survive much longer [than Yugoslavia]. The Greeks had support from the British divisions. But the Greek forces were suicidally positioned. German forces broke through the Monastir gap between the Greek armies in Albania and Salonika and pushed southward. The Graeco-British front collapsed as one position after another was outflanked. British troops, harried by the Luftwaffe, fled south to find harbours to escape. On April 27, German forces occupied Athens.”

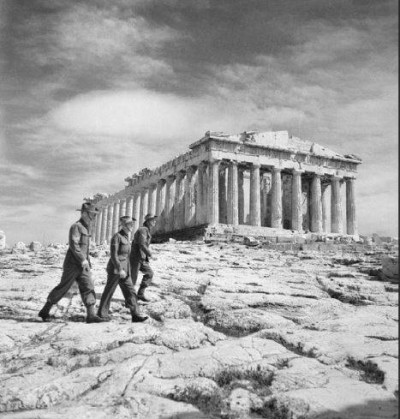

Anzac soldiers at the Acropolis in 1941.

The Kiwi troops had arrived in Athens on March 27 and, after some sightseeing around the Acropolis, set up a defence line on Mt Olympus as part of the British forces. The record shows 2 New Zealand Division included 23 Battalion, made up of South Islanders.

Worth creates a fictional D company of three platoons, and from there, he imaginatively reconstructs events over that month until the evacuation from the beach of Monemvasia on the southern Peloponnese coast on April 30.

The titular character is Second Lieutenant Neil Rankin, a sharpshooter who leads his men throughout the retreat.

The early scenes – as the Kiwis prepare to hold back the advancing Germans, with their air support – are slow to get going. Too many characters, and much crude and profane dialogue, are wasted on depicting the variety of their backgrounds and attitudes.

A ruthless editor would have cut the clichés, expletives, and redundant prose: hearts that sink, thump, and pound; sweaty palms, bated breaths, and churning guts; phrases such as bitten off more than can be chewed, cat among the pigeons, and shaking like a leaf.

The second part of the story is much different. The language becomes more succinct and urgent as the enemy takes its toll on the Kiwi and other soldiers. Villages are occupied, abandoned, and reduced to rubble.

Rankin has a brief fling with a Greek woman, who combines a romantic picnic with some military reconnaissance. Worth gives detailed descriptions of the weapons, vehicles, and aircraft on both sides, underlying his comprehensive research.

Monemvasia today at the southern tip of the Pelopponese coast.

While the characters remain two-dimensional, the geography and underlying history of the region is solid and informative. The battle at a bridge over the Corinth canal is a superb action piece, suggesting Worth has a future in this type of writing. The evacuation to Crete is also full of suspense, with the next chapter of the story yet to be told.

The novel was written as a tribute to a generation of men and women who grew up during the Depression of the 1930s, had their lives put on hold for five years, and, for those who survived, returned to rebuild a country without revealing much of their experiences. More of these stories must exist in memories and imaginations.

The Rabbit Hunter, by Christopher Worth (Renaissance Publishing).

Nevil Gibson is a former editor at large for NBR. He has contributed film and book reviews to various publications.

This is supplied content and not paid for by NBR.

Sign up to get the latest stories and insights delivered to your inbox – free, every day.