Bitter legacy of Cold War’s psychological scars

OPINION: Russia’s ethno-nationalism fills void left by West’s victory over communism.

OPINION: Russia’s ethno-nationalism fills void left by West’s victory over communism.

The commentaries and analysis of Russia’s justification and performance in its invasion of Ukraine are usually phrased within a historical context. The desire to remain a military superpower, its need for a security ‘buffer’ against its western neighbours, and uniting people with a common cultural heritage are three common strands.

Under President Vladimir Putin, and shorn of its communist ideology, Russia is trying to recover what it perceived as lost when the Soviet Union imploded in 1991. At first it seemed Russia and some breakaway parts of the Soviet Union would veer toward Western-style democracies, at least in Europe, eventually becoming consumer societies content to stay within their own boundaries.

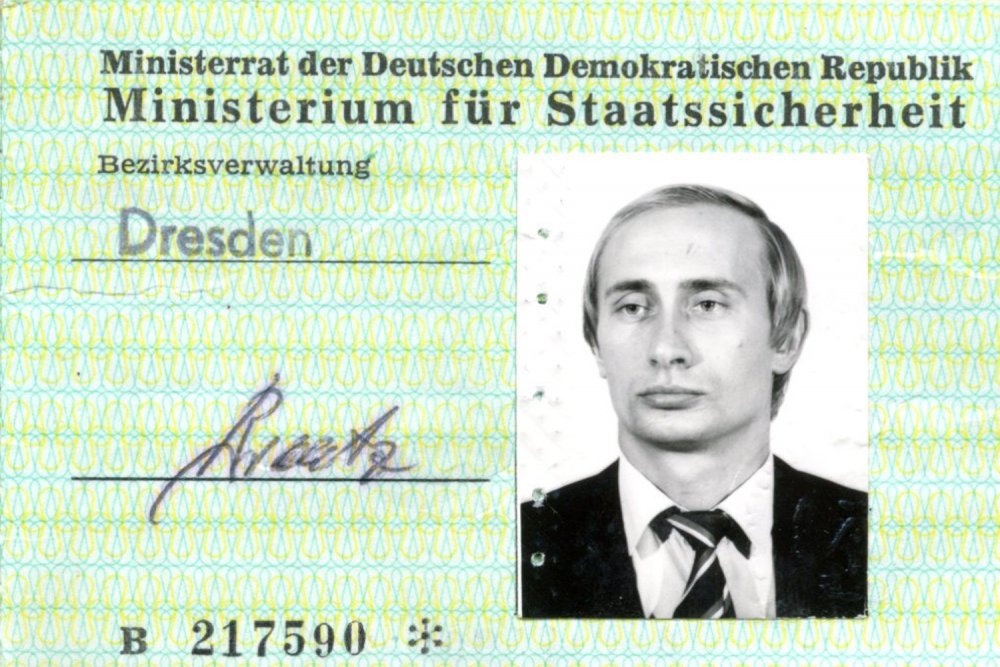

Rise of Putin

But the rise of Putin and the Kremlin’s military-intelligence bureaucracy proved more than a match for the economic and political chaos that followed. In less than three decades, the strengths that enabled the Soviet Union to last as long as it did returned – dictatorial control over its people, and the ability to wage wars through psychological and non-military means as well as conventional weapons.

These were first used against former parts of the Soviet Union - Chechnya, Georgia, Crimea – as well as defending the Syrian regime of Bashir Assad, all with brutal effect. The wider world also felt the effects of Soviet techniques used since its inception in 1917.

The non-military menu included a range of political, socio-economic, and media tools for subversion, disinformation, forgery, manipulation and, more recently, cyber-attacks. Putin learned these in his training as a KGB spy, which he completed in 1985.

His regime has a well-documented record of using false news and outright lies to disrupt Western democracies, from elections and campaigns to supporting causes that stir up racial tensions and reduce the effectiveness of police and defence forces.

The emphasis on psychological warfare – which also encompassed sport, the arts, music, and literature – was a notable feature of the Cold War for 50 years from the late 1940s. Though hundreds of books have charted this period of history, few have tackled it from a purely psychological angle.

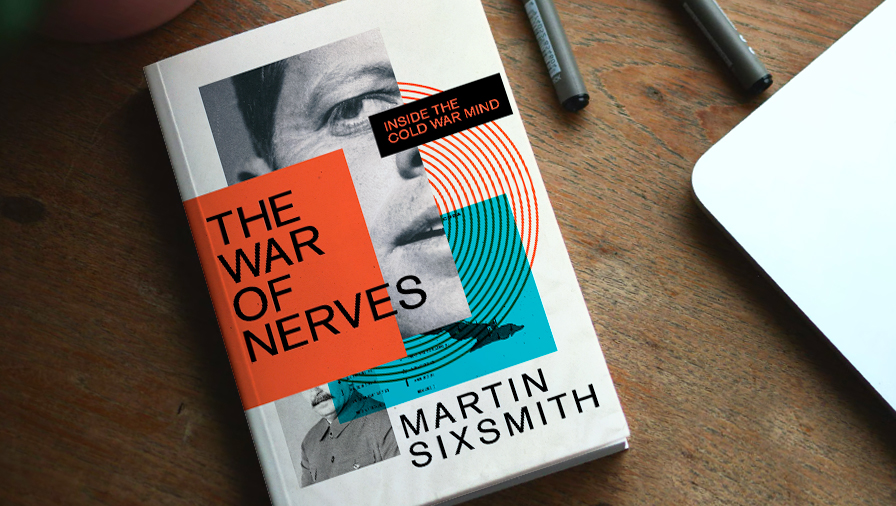

That task was seized by Martin Sixsmith, a BBC journalist who spent nearly two decades as a foreign correspondent in Brussels, Warsaw, Moscow, and Washington DC between 1980 and 1997. He studied Russian at Oxford, Harvard, and in St Petersburg, backing this up with psychology at Birbeck and London Metropolitan University.

The result is The War of Nerves: Inside the Cold War Mind, written with his son Daniel, who did most of the research. The book runs to 577 pages, excluding the bibliography and source notes, which are available at a dedicated website.

Psychological tools

Sixsmith starts with an explanation of his psychological tools, including a theory of the mind and reasons why, after World War II ended, not all the victorious Allies followed the same path of peace and prosperity that was also enjoyed by the defeated enemies.

Instead, one side promoted a view that it was under constant attack from the other, with little understanding and knowledge about the adversary. Of course, the capitalist societies of the West were more aware, if only because of writers such as George Orwell.

The eastern half of Europe had no choice after 1945 and was told that democracy on the other side of an ‘iron curtain’ was a sham, where the levers of power were exercised by the hidden hand of industrialists and financiers.

Why did the USSR and its captive nations reject the alternative? It’s a psychological question that Sixsmith spends much effort in explaining. Soviet historians blamed “Western belligerence” in the 1920s for why Russia rejected social and democratic reform.

Three summits

During World War II, Winston Churchill held three summits with Joseph Stalin, in Moscow, Teheran, and Yalta. Stalin knew little of the West (unlike Lenin and Trotsky) and was suspicious of everyone after being tricked by Hitler in the 1941 pact that divided eastern Europe between the Soviet Union and Germany.

Churchill’s views and demeanour have been well documented. Not so much Stalin, who surprised his British and American counterparts with his intransigence. He was also confident that victory, with his armies having occupied half of Germany and Austria, should give him back what Hitler had agreed.

Churchill was unable to get American backing for an independent Poland, effectively meeting Stalin’s demands. But his paranoia could not be satisfied, particularly because at that stage he did not have a nuclear bomb.

“The Cold War would grow from disagreements about the best way to maintain prosperity and peace, not from a desire on either side to fight,” Sixsmith writes.

Clear-headed analysis by American diplomat George Kennan and psychologist Karen Honey strengthened the Western powers’ resolve to resist Stalin’s personality cult. But even they underestimated the “extent of Stalin’s personal power and the depth of his mental aberration”.

Spies who stole the secrets of nuclear warfare was a further blow, as it reinforced Stalin’s belief in his invincibility.

“The Kremlin was adept at using lies and deceit, infiltration, and disinformation to wrong-foot both its former allies and its own population,” according to Sixsmith. Its propaganda emphasised demands for disarmament (but not its own), withdrawal of foreign troops, the inequality of capitalism, the class struggle, and opposition to colonialism and racism.

Success and failure

The Cold War in the 1950s saw successes and failures on both sides, each hobbled by a misunderstanding of the other. Sixsmith examines these in detail: the power vacuum after Stalin’s death and lack of response to the East German uprising in 1953; Nikita Khrushchev’s ‘secret speechv against Stalinism in 1956 that sparked the doomed Hungarian revolt; and the Soviet Union’s triumph of launching the Sputnik satellite in 1957 as a symbol of technological superiority.

The psychological battle was fought in homes as well as space. An American exhibition of kitchen appliances in Moscow in 1959 was a consumer’s dream but Khrushchev was unwilling to concede inferiority and lied to do so. He promised President Richard Nixon, who engaged in a lively debate at the show, that it would be broadcast in full, as it was in America. Sure enough, Soviet television edited it to fit only their perspective.

Khrushchev’s ebullient defence of communism was reinforced by Yuri Gagarin becoming the first man in space, followed two years later by the first woman cosmonaut in 1963. But these efforts had pushed the Soviet space machine beyond its capabilities, and no Russian ever walked on the moon.

Khrushchev’s unpredictable character and false knowledge of the West eventually led to his downfall, as the Kremlin was forced to back down on his “adventurism” over the Cuban missiles. The Soviet leader’s legacy also included the Berlin Wall, the most obvious symbol of socialist failure to those living in the West.

Gained traction

The only issue in which the Soviets gained traction abroad in public opinion was support for peace groups opposed to nuclear weapons, which also undermined the West’s military and defence policies. Later, the Soviets were able to add other causes as they exploited disinformation about Aids among African Americans and spread false news through organisations devoted to anti-racism, decolonisation, and policing.

Khrushchev’s successors showed none of his flair or even belief in their system’s superiority as memories of the 1960s faded. The Cold War ended abruptly when the “radiant future” could no longer be sustained.

Despite his reforms, and the final blow of the Chernobyl nuclear power plant meltdown, Mikhail Gorbachev misread the psychology of the Cold War. He hoped his relationships with President Ronald Reagan and Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher would ease the Soviet Union and its satellites out of their dire economic and social predicament.

“But four decades of entrenched hostility could not be wiped away,” Sixsmith concludes. ”With the communist monster at their mercy, the Western powers were hardly going to take their foot off its throat.”

In today’s context, with Russia in hot war mode to regain control of the most western part of the Soviet Union, a successful campaign by Ukraine might make it harder for Belarus and Russia to survive as the last European dictatorships.

However, Sixsmith says of the hubris and insensitivity toward the defeated enemy in 1991 backfired. The end of communism did not mean the Russian psyche, after centuries of abuse by rulers and foes, would change overnight.

Putin has never resiled on his view that the breakup of the Soviet Union was catastrophic, and that the chaotic decade of the 1990s did nothing to indicate the West was as generous as it was to Germany and Japan. The result is a more virulent form of ethno-nationalism, backed by preparedness to use military force, that would surprise even the most hawkish of the post-Stalin Cold War communists.

The War of Nerves: Inside the Cold War mind, by Martin Sixsmith (Profile Books, in association with the Wellcome Collection).

Nevil Gibson is a former editor at large for NBR. He has contributed film and book reviews to various publications.

This is supplied content and not paid for by NBR.

Sign up to get the latest stories and insights delivered to your inbox – free, every day.