Bill Andersen’s impossible dream

OPINION: Revealing biography of communist trade unionist’s unfulfilled life.

NBR columnist Nevil Gibson speaks with Calida Stuart-Menteath

OPINION: Revealing biography of communist trade unionist’s unfulfilled life.

NBR columnist Nevil Gibson speaks with Calida Stuart-Menteath

British philosopher Roger Scruton entitled his commentary on the thinkers of the New Left as “fools, frauds, and firebrands.” It’s a good description of the far-left fringe of politics.

Communism failed because it meant the suppression of long-standing and diverse ideas that were the basis of social organisations and institutions, such as courts, schools, churches, charities, clubs, and cultural groups.

That group also included trade unions, which arose as the industrial revolution and market-based capitalism created a working class. Marxism was based on notions that labour created “surplus value” to enrich the owners of capital.

The class struggle was also part of a “progressive” view of history that socialism – the abolition of property ownership – would replace capitalism with a society that required no laws, no property, and no chain of command.

“The contradictory nature of the socialist utopias is one explanation of the violence involved in the attempt to impose them; it takes infinite force to make people do what is impossible,” Scruton wrote.

Instead, the historic role of trade unions has been reformist, extracting gains from the capitalist system to greater or lesser degrees, usually dependent on how much freedom exists in any society.

The history of the labour movement in New Zealand is well documented, thanks to generous support for researchers and their zeal for the cause, often based on their own activism. One of the leading practitioners is Cybèle Locke, daughter of poet, teacher and Youthline founder Terry Locke.

Cybèle Locke began her interest in far-left politics at the University of Otago in the late 1990s.

Cybèle Locke was active in far-left politics at the University of Otago in the late 1990s and, in 2012, after an academic career in the US, wrote Workers in the Margins, a history of union radicals in the post-World War II period.

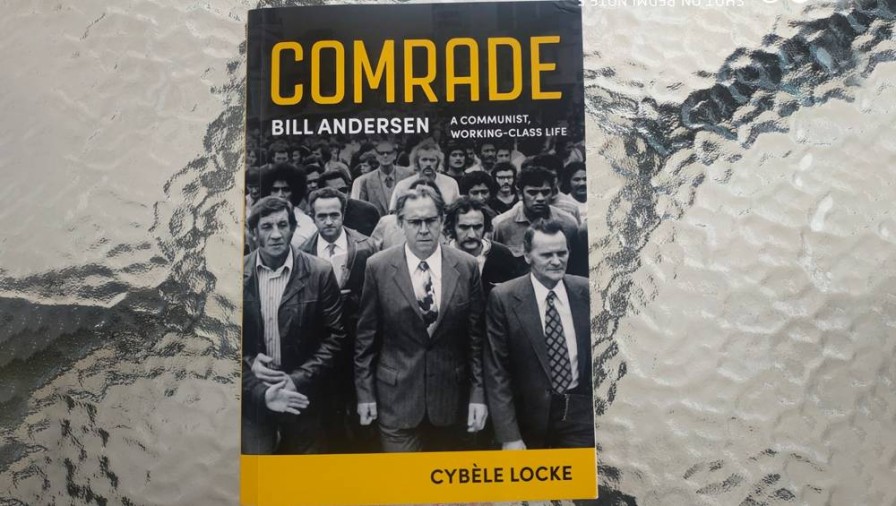

Her latest, Comrade Bill Andersen: A communist, working-class life, is nearly twice as long and shows the same depth of scholarship. It runs to more than 400 pages with 70 of them being copious source notes and an index. Though it doesn’t have a bibliography, the sources are the most comprehensive I’ve seen on the far left and unionism in New Zealand.

Locke interviewed 40-odd people who knew Andersen and had access to his private papers, including an uncompleted memoir. She also viewed files held by the Security Intelligence Service (SIS) and its predecessors. However, she was denied access to the 22 volumes on Andersen’s connections with the Soviet Union. These would likely make a book in themselves, given the recent revelations about the extent of the KGB's activities.

Instead, Locke concentrates on Andersen’s union and political activity, as well as his private life. He became a communist in 1946 after a stint in the merchant navy during World War II. He was motivated by the poverty he saw in the Middle East and the treatment of ship crews.

The Communist Party (CPNZ) had just 1000 members, but they were a majority on the Auckland Trades Council. The Labour government was strongly anti-communist and so were the unions that supported it. The government favoured ballots to approve strikes, something the communists opposed, as they did conscription.

Andersen spoke out about both, beginning his lifelong surveillance by a special branch of the police and then the SIS. Conscription was carried by a public referendum in 1949, the same year Labour was voted out of power.

The Soviet Union heavily promoted the international communist cause both openly and covertly after World War II as Stalin faced a hostile West. He encouraged united front organisations, such as the World Peace Council (WPC), whose main aim was to oppose nuclear weapons and weaken the enemies of socialism.

Andersen supported the WPC and was a member of the Waterside Workers’ Union, which with carpenters, miners, drivers and labourers formed the Trade Union Congress in 1950 after breaking away from the Federation of Labour. Soon after, the watersiders were locked out in the 1951 dispute.

That lasted 151 days, with Andersen playing a key part as the head of printing and propaganda. The CPNZ debated ideology and trade union strategy. Two top members were expelled for “economism” – putting wages and conditions ahead of revolutionary theory.

As a deregistered watersider and unable to work on the wharves, Andersen became a truck driver as the CPNZ sought influence in unions that supported the FOL and the arbitration system. Throughout his career, Andersen practised “revolutionary pragmatism” that believed unions imperilled their future if they pushed strikes “beyond their peak”.

In 1956, he took his first union position in the Northern Drivers Union (NDU). Unions began to rebuild their power through major public works projects, while maintaining pressure to break the conciliation and arbitration system with its industry-based awards.

A decline in the economy in the mid-1960s after the collapse of wool prices saw unions focus on traditional issues that remain today: a living wage, price controls, and full employment. Direct bargaining, pushed by the militant unions, threatened the arbitration system when a nil general wage order was declared in 1968.

Meanwhile, revelations after Stalin’s death in 1953, savage repression of revolts against working conditions, the lack of freedom in the socialist bloc, and heightened tensions during the Cold War revealed communism as a “god that failed.”

Andersen remained among a dwindling band of believers. He opposed New Zealand’s role in Malaysia to counter a communist-led insurgency, as well as the Anzus pact and intervention in Vietnam.

In 1965, Andersen and Ken Douglas, another prominent communist union leader, visited China, which then wasn’t recognised by the New Zealand government. They were not impressed and sided with the Soviet Union in the Sino-Soviet dispute.

This split the communists, with the CPNZ majority backing China (and later Albania) while the unionists formed the Socialist Unity Party (SUP). The global ferment of 1968 threw up a new generation of radicals. The SUP and the NDU embraced broader issues, such as equal pay for women and maternal leave, racial discrimination and Māori advancement, apartheid in South Africa, the Vietnam War, nuclear testing, and dawn raids.

Bill Andersen ‘stopped Auckland’ in 1974 before he was cleared of charges. Photo: Auckland Trade Union Centre.

Unions became notorious for their disruption and strikes. The quote of the decade was Prime Minister Norman Kirk’s “To put it mildly, the public have had a guts full, and so have we.” He said this in 1974 as Andersen became the “man who stopped Auckland” over his arrest during a union fuel boycott.

The Labour government faced a worldwide inflation spike in oil prices and unions intent on breaking a wage freeze. The then Rob Muldoon won the 1975 election with a pledge of resistance to militant unions. This culminated in a general strike (1979) and annual stoppages that rose to record levels. Inflation was rampant and wage demands often surged to 25%.

In 1981, the SUP had just 230 members and was viewed as a “handbrake” on militancy.

Andersen and Muldoon debated on TV, with Muldoon’s belligerence countered by Andersen’s even-tempered response. Andersen’s dogmatism was best reflected in his strategy of “Be polite, logical and very, very firm.”

The “guts-full” public responded with the anti-union Kiwis Care march on Queen St. On the international scene, socialism took further blows with Solidarity in Poland again drawing attention to the SUP’s pro-Soviet views on the role of trade unions.

The radical Left, now dominated by university students, embraced post-modernist identity issues of race and gender, while the labour share of wages in the economy started a 14-year decline from 1987, according to a union analysis. Andersen lamented the focus on wage gains instead of the bigger picture of fighting for a socialist society.

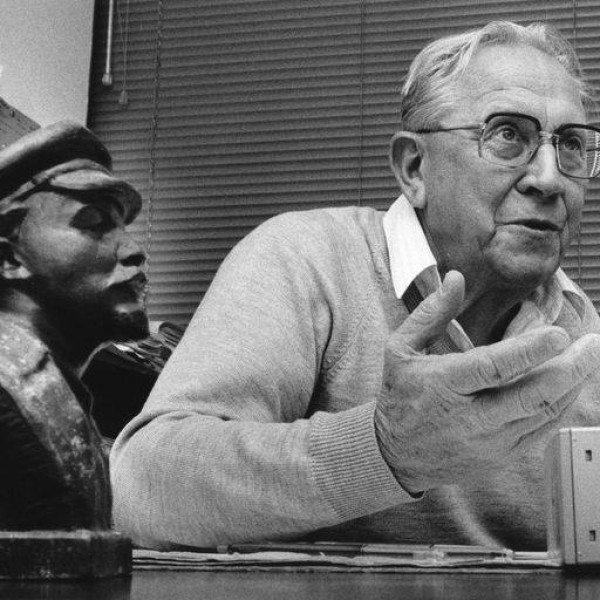

Bill Andersen, watched by Lenin, explains his resignation from the SUP in 1990. Photo: NZME.

The moderate unions signed a Compact with a Labour government that was about to lose the 1990 election. Andersen was torn between SUP support for the Compact to protect union power and the socialist ideology that opposed it. He resigned from the SUP as the Soviet Union collapsed.

Locke describes the SUP as afflicted by “paralysis and confusion.” Douglas also quit the SUP, saying socialism was no longer a viable option. Andersen and his few supporters formed the Socialist Party of Aotearoa (SPA), which became just another sectarian group on a heavily fragmented Left.

Andersen’s fears of a disunited union movement were realised when the militants again broke away from the Council of Trade Unions (CTU) to form the Trade Union Federation in 1993. Andersen was described by Bruce Jesson as one of the ‘old guard’ of self-educated, working class union officials who had been replaced by tertiary-educated graduates in the CTU, a merger of the FOL and the white-collar public service unions. Andersen even gave an interview to NBR in 1965.

The SPA withered away after Andersen’s death in 2005 at 82 and still employed by the NDU. It had become part of a much bigger one but like most others it faced legal as well as financial hurdles as membership declined. The unions were wedded to economic growth and viewed the state’s role as protecting jobs.

Andersen, by contrast, rejected the focus on increasing wealth rather than its redistribution. Locke depicts Andersen as a man whose mild-mannered temperament was with the underdog but who was unwilling to compromise his views.

It is tempting to know how he would have fared in a socialist regime where his support for democratic unionism would be a handicap, and whether he would have been one of those who discredited the utopian socialist dream from the start.

Comrade Bill Anderson: A communist, working-class life, by Cybèle Locke (Bridget Williams Books).