Behind the scenes: Hemingway in 1920s Spain

A literary conceit imagines what could have really happened.

WATCH: NBR columnist Nevil Gibson speaks with Calida Stuart-Menteath.

A literary conceit imagines what could have really happened.

WATCH: NBR columnist Nevil Gibson speaks with Calida Stuart-Menteath.

Paul Auster at the Brooklyn Book Festival in 2010.

American writer Paul Auster’s death from lung cancer in New York on April 30 prompted a series of tributes in leading world newspapers and magazines. I was curious because I had never heard of him.

Usually, my ignorance of prominent literary figures are reserved for Nobel Prize winners who live in places such as Norway or Belarus. One of the longest obituaries for Auster came from the English version of Le Monde, which described him as “one of the most brilliant of his generation, he was also perhaps the most Francophile”

Auster had studied French literature at Columbia University and lived in Paris from 1971-74. He returned to New York, but his writing career did not take off until 1982 with The Invention of Solitude, inspired by the sudden death of his father three years earlier. Auster was 77 when he died, having just completed his latest novel, Baumgartner, which was published only a few weeks ago.

Le Monde described him as an “artist in the art of storytelling [who] drew on his childhood, his history, what he called his ‘interior’, to nourish his novels, autobiographies, and even political text, with extreme intelligence and sensitivity”.

The BBC replayed a sympathetic 2021 HARDTalk interview with Stephen Sackur, who is notorious for ambushing his subjects. In it, Auster likens reading a book to a one-on-one relationship between the writer and the reader.

Dermot Ross.

Sight & Sound, the film magazine, recounted Auster’s interest in the cinema. He directed a few movies and some of his 40 books were adapted for the screen. Again, I had never heard of any of them and none, to my knowledge, has screened in New Zealand. The magazine linked Spanish director Pedro Almodovar’s Pain and Glory, which I did see, “as a kind of homage” to Auster.

In the pantheon of American literature, Auster was a generation after the great burst of male novelists who emerged after World War II: JD Salinger, Jack Kerouac, Norman Mailer, Saul Bellow, John Updike, Philip Roth, Joseph Heller, Truman Capote, William Styron, and Thomas Pynchon.

Many of those were still prominent in the 1980s, when the likes of Don DeLillo, Larry McMurtry, David Foster Wallace, Tom Wolfe, Jonathan Franzen, and Cormac McCarthy came along. But my interest in modern American literature sagged after that and I turned back to those of the 1920s and 1930s: John Steinbeck, F Scott Fitzgerald, William Faulkner and, of course, Ernest Hemingway – perhaps the best of them all.

Hemingway’s passport photo (1923).

My enthusiasm for Hemingway is shared by many others. His first novel, The Sun Also Rises (1926), was referenced in the 2017 Netflix western series Damnation where it is being read by a young journalist. It was also essential reading for Eric Blair (later George Orwell) in Paul Theroux’s latest novel, Burma Sahib.

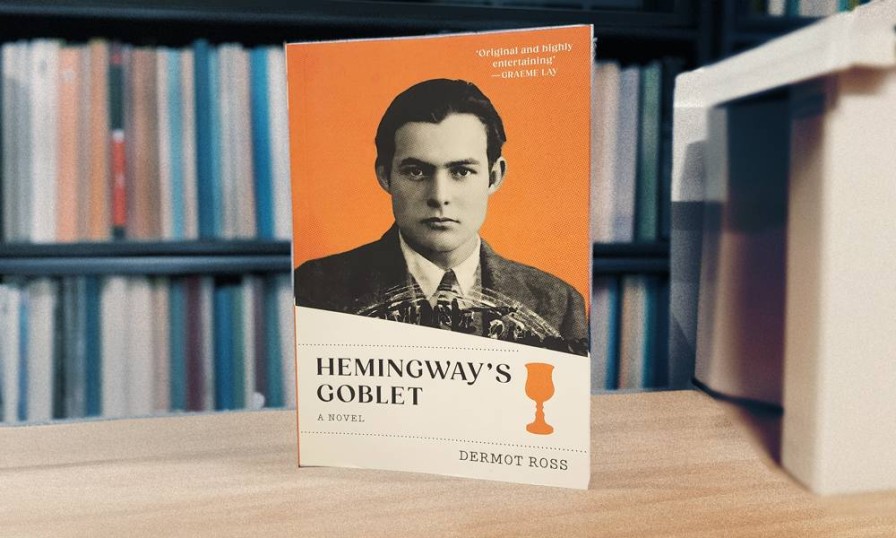

Another fan is Auckland commercial lawyer Dermot Ross, who has ingeniously turned his lifelong interest in the author into a novel, Hemingway’s Goblet. I say ingeniously because its structure is reminiscent of The Master and Margarita, which I recently praised as the greatest book of the 20th century.

Both have a story within a story, although Ross would not claim his could be compared with Mikhail Bulgakov’s use of the Easter Passion in a satire about the hypocrisy of socialist morality in Stalin’s Soviet Union.

Nick Harrieson, the character at the centre of Ross’s story, is a London university law lecturer whose main achievement is to explain legal terms while filling out a crossword. He is hit with a sexual harassment claim from a female student, Korean-born Adrienne Kim, sending his career into limbo.

Hemingway, left, in Pamplona, 1925, with wife Hadley, centre.

He uses the downtime to discover manuscripts left by his grandfather, William Forbes Harrieson, who was among Hemingway’s coterie who boozed and wooed their way through a Spanish summer in 1925. The first memoir, written in 1927 when Harrieson was a colonial officer in Kenya, provides a much different account of the characters and events depicted in The Sun Also Rises.

Among them is the claim that Hemingway plundered many of the ideas and quotes from Harrieson. These provided many of the titles for later novels and short stories, such as The Green Hills of Africa, For Whom the Bell Tolls, and Across the River and into the Trees.

It details how Hemingway fictionalised two male characters into one, left out his then first wife Hadley altogether, though the book is dedicated to her and their son, distorts events concerning Harrieson himself (Harris in the novel), and claims war hero status for Jake Barnes, the novel’s narrator and the assumed identity of Hemingway.

Worse, Harrieson states that Jake doesn’t display any of Hemingway’s bad behaviour as a lecher who chases after servant girls, hits his wife, is prone to violence, and acts like a petulant child.

The second memoir, in a letter sent from Malaya before Harrieson’s death in 1943 while working on the Japanese Thai-Burma (‘Death’) Railway, recounts an encounter with Hemingway at Hong Kong’s Peninsula Hotel in 1941. During their meeting, three Chinese prostitutes appear in what could be a Russian honey trap.

Hemingway, right, with Martha Gellhorn in China, 1941.

Nick consults an expert on Hemingway who declares the “unremarkable and decent” Harris as a true depiction of Harrieson. But the expert’s verdict on Hemingway is completely different. He whitewashes Jake while, in reality, Hemingway doesn’t let go of grudges and slights.

The expert goes on: “Hemingway himself emerges from your grandfather’s writings as even more grotesquely a caricature of the man the world knows. Boorish, aggressive, anti-Semitic, a drunkard, volatile, misogynistic, a sexual predator.”

First edition (US) cover, 1926.

This is a devastating critique, but remember this is fiction and provides a modern-day judgment in a world where a man’s job can rest on the word of an aggrieved party. The twist is that Nick’s accuser is a Korean student who becomes his lover.

They spend time revisiting Pamplona and Burguete, the setting for the bullfighting and fishing scenes respectively in The Sun Also Rises. But Nick is no innocent himself. His lover is perceptive, describing him as narcissistic, manipulative, and deceptive. He is a self-satisfied Guardian reader to boot.

Ross is on tricky ground with this literary conceit but it’s a good read and should find an appreciative audience. It is also a sharp contrast to Hemingway’s main claim to literary fame.

My copy of Fiesta (the London-published title for The Sun Also Rises) is a lean 140 pages of spare prose, said to be inspired by the style book of the Kansas newspaper where Hemingway first worked. By contrast, Hemingway’s Goblet runs to more than double that length, displaying the wordiness that is a mark of today’s creative writing classes.

Ross has fact checked from his extensive library of 50 books on Hemingway what happened in Spain in 1925 and Hong Kong in 1941, before the Pearl Harbour attack brought the US into World War II. It’s left up to readers to decide whether the described events could be true.

Footnote: Ross is far from the first to use Hemingway’s life as a vehicle for fact or fiction. A recent example is Mark Kurlansky’s The Importance of Not Being Ernest (2022), in which he mixes his own background as reporter and writer into a portrait of a man whose work he has admired since childhood. For a modern example of Hemingway’s style, read Stephen Daisley’s A Better Place, a finalist in this year’s Ockham book award for best fiction.

Hemingway’s Goblet, by Dermot Ross (Mary Egan Publishing).

Nevil Gibson is a former editor at large for NBR. He has contributed film and book reviews to various publications.

This is supplied content and not paid for by NBR.