Auckland history: Stories of what lies beneath

OPINION: Archaeology doesn’t tell full story of how people lived in Tāmaki Makaurau.

OPINION: Archaeology doesn’t tell full story of how people lived in Tāmaki Makaurau.

The writing of history puts its practitioners in the front line of the cultural wars. This is due to the dominance of postmodernism and the need in the jargon to control or change what is called The Narrative. In its crudest form, as outlined by George Orwell, this is a propagandistic tool to have just one version of history, as is the case in a totalitarian regime such as China.

A more sophisticated rewriting is aimed at the Standard Narrative, a product of the European Enlightenment that follows the evolutionary progression of humankind through various stages of development – from hunting and gathering to pastoral farming and on to industrial society, cities, and the modern state.

The popularity of macro-history – volumes such as Jared Diamond’s Guns, Germs and Steel (1997) and Yuval Noah Harari’s Sapiens (2016) – is proof that people are interested in the deep tapestry of the Standard Narrative. The latest attempt has come from two Americans, anthropologist David Graeber and archaeologist David Wengrow, in The Dawn of Everything, the first of four planned books.

However, Graeber died in September last year, aged 59, and the project’s future is in doubt.

Activist anarchist

He is best known as a radical activist from the Occupy Wall Street and Extinction Rebellion movements. His books include Debt: The First 5000 Years (2011) and Bullshit Jobs (2018), in which he describes the modern communications and human resources industries, among others, as “paid employment that is so completely pointless, unnecessary, or pernicious that even the employee cannot justify its existence”.

The Dawn of Everything argues that over 10,000 years, early human societies were diverse and developed numerous political structures. Some were large, complex, and decentralised, challenging notions of how the ‘civilised world’ of Europe and parts of Asia was more advanced than indigenous societies encountered during the age of discovery, from the 17th century onward.

Archaeology is the basis for such history, and the book raises issues, such as: just because most hard evidence comprises valuable artifacts, tools and permanent structures, that doesn’t mean other societies weren’t just as organised and successful but left few traces. This particularly appeals to Graeber, an anarchist who believes it’s possible for societies to exist without a coercive power structure.

Relevant departure

This revision of the Standard Narrative is relevant when considering a new history of Auckland, Shifting Grounds, by Dr Lucy Mackintosh, curator of history at the Auckland War Memorial Museum and author of many studies on the city’s archaeological past. The text and lavish illustrations are integrated into a layout that distinguish yet another excellent production from Bridget Williams Books.

Unlike some recent examples of revisionist history, Mackintosh does not clout her readers but gently suggests the work of earlier Auckland historians, such as John Waite, Percy Smith, Francis Dart Fenton, and George Graham, are merely “outdated” and “problematic”.

Of course, their books are quoted, as are newspaper accounts, but the purpose is to tell the story of this volcanic isthmus through its three most prominent physical features (Tāmaki Makaurau could be translated as ‘desirable place of eruptions’). These landmarks are the Ōtuataua stonefields at Ihumātao (scene of recent land protests); the Auckland Domain, also known as Pukekawa (‘place of bitter memories’); and Maungakiekie or One Tree Hill, the country’s largest and best known pā site.

All three have literal underground histories that are either hidden or obliterated by more recent events that occurred in the city’s growth to become one of the world’s most admired cities.

Volcanic gardens

Today, the stonefields are sandwiched between Auckland International Airport and Watercare’s sewage treatment station on the shores of Manakau Harbour. The volcanic soil and basalt rocks were ideal for gardening, particularly kumara, and are “one of the few remaining places where this wider context of Māori agriculture and settlement … can still be seen.”

This was also where some of the earliest influences of European crops, livestock, and tools were adopted by Māori before the “considerable disruption” of the Musket Wars in the 1820s and 1830s. At some period, farming was abandoned but resettlement occurred from 1835 onward, with Auckland soon after becoming the capital (1841-65) and the seat of four British governors.

A Wesleyan (Methodist) mission was part of the settlement from 1846 but another major disruption occurred after conflict broke out in Taranaki in 1860. Governor George Grey was advised – wrongly, most historians concur – that tribes in the Waikato were planning to invade Auckland.

He expelled Māori from Ihumātao, where the Kingitanga movement began in an attempt to give all tribes a ‘king’ to represent them in dealings with the British Crown. The land was officially seized in 1864, with the Aborigines Protection Society at the time branding the expulsion as a “cruel and unprovoked deportation”. The law’s inability to uphold land rights made it “a crooked place,” as one leader put it.

The stonefields proved unsuited to European pastoral farming, as it could not be ploughed, but stone fences remain as part of an historical reserve. The return of other land under a government deal with Fletcher Building redressed some of this long-standing grievance.

This was not the case with Mackintosh’s two other landmarks. Auckland’s leading citizen for much of the 19th century, Sir John Logan Campbell, was crucial to the fate of Maungakieke, usually described as a fortified pā. But she throws doubt on this, saying recent evidence indicates the terraces were more widely used for cultivation, food storage, and accommodation rather than for warfare.

Chopped down

The summit had originally featured a lone totara – hence the name Te totara-i-ahua (One Tree Hill) – and then a pohutukawa, which was chopped down in 1852 by a European settler. Campbell replaced it with Monterey pines from California, as part of his wider experimentation with introduced flora. The adjoining Cornwall Park, originally Campbell’s farm, has the remnants of a large olive grove. This was inspired by Campbell’s extensive travels in the Mediterranean and his notion that olives and grapes could provide new horticultural industries.

However, the export of olives to California proved unsuccessful because of their bitterness, thought to be due to the lack of processing and preservation skills. (Today, those olives have produced award-winning products.)

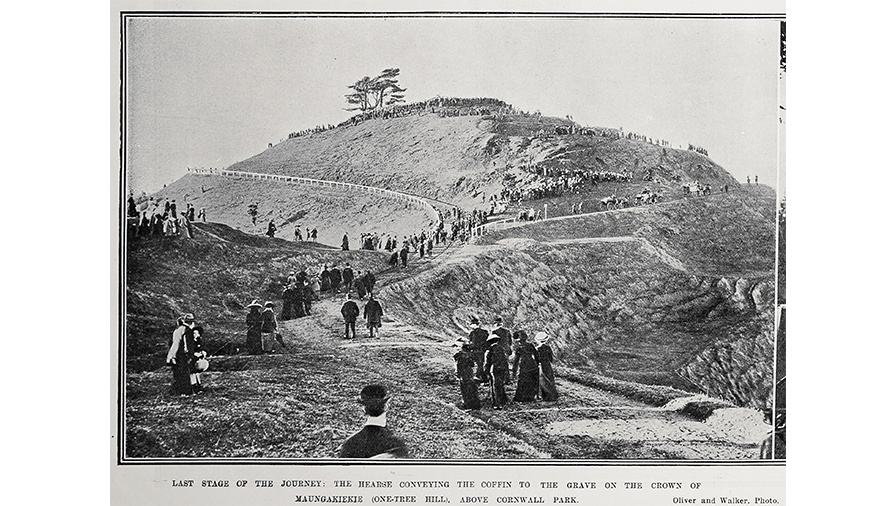

Campbell’s biggest impact was his desire to be buried at Maungakiekie, against the wishes of his family. In 1907, before his death, he also proposed a 30m obelisk as a memorial to Māori. Finally completed in 1940 but not officially unveiled until 1948, it remains Auckland’s most distinguishing landmark, apart from the harbour bridge. Mackintosh describes the use of an Egyptian icon as “out of time and place”.

Maungakiekie had long been a centre of controversy, even since its restoration to Māori. Its slopes were a golf course from 1901-09, and water storage tanks were also built there. The construction of the summit road, to fulfil Campbell’s obelisk plan, uncovered caves protecting human remains from desecration or theft. This posed a cultural dilemma, as the graves were tapu but neither did they conform with Western values that individuals keep their identities after death.

Mackintosh’s text is informed by items found during the construction and now stored at the museum. Exploration of the caves was quickly suspended and they remain untouched.

Original use

Also wiped from history is much of the story of Pukekawa, some 1200ha donated by Ngāti Whātua in 1840 and designated in 1844 as an area for public recreation. Apart from exotic flora, it was also the base of the Auckland Acclimatisation Society, which imported birds, fish, and animals such as kangaroos, monkeys, rabbits, and deer. Later, the Domain housed temporary industrial exhibitions to display economic progress, the last of which in 1914 left only the permanent tea rooms and botanical garden.

One area was devoted to market gardens run by the Ah Chee family, demonstrating that Auckland’s settlement history also involved other cultures than European and Māori. The gardens ran into trouble with the rise of unionism and demands for a 40-hour week. Industrious Chinese ignored such conditions, and were often prosecuted for working on Sundays. Competitors said the cheap vegetables undercut their own.

In 1920, the gardens were turned into Carlaw Park and the area is now a business centre. After Chan Ah Chee returned to China, his grandson Thomas expanded the family’s retail business, establishing the country’s first supermarket chain, Foodtown, as well as Georgie Pie.

Pukekawa’s original name was better honoured when it became the site of the neo-classical museum, built in 1929 to commemorate lives lost in World War I. It’s a sharp contrast to the cottage that once housed Waikato rangatira Pōtatau Te Wherowhero but appropriately echoed victims of earlier “bitter memories” that left no trace above or below ground.

Mackintosh admits her choice of three landmarks ignores other overlooked features of Auckland’s physical history, such as the military barracks, the heritage of the Jewish community and Puhoi’s Bohemian settlers, and the air raid shelters under Albert Park. No doubt these will surface in due course as the writing of history continues from whatever angle.

Shifting Grounds: Deep histories of Tāmaki Makaurau, by Lucy Mackintosh (Bridget Williams Books)

Nevil Gibson is a former editor at large for NBR. He has contributed film and book reviews to various publications.

This is supplied content and not paid for by NBR.