A second Cold War: Freedom needs new defenders

ANALYSIS: Why the West must protect its intellectual heritage.

WATCH: NBR columnist Nevil Gibson speaks with Calida Stuart-Menteath.

ANALYSIS: Why the West must protect its intellectual heritage.

WATCH: NBR columnist Nevil Gibson speaks with Calida Stuart-Menteath.

University of Canterbury philosophy academic Mike Grimshaw has called for a new cultural cold war to defend liberalism against its enemies on the Left and Right.

The difference is that the war is being fought within liberal democracies rather than against the threats of, say, Russia, China, or Iran.

Grimshaw cites the example of the Congress for Cultural Freedom, an outfit established in 1950 to promote and defend the West’s values against totalitarian regimes and institutions. Some with long memories may recall publications such as Encounter and Problems of Communism, both vehicles for conservative and liberal anti-communist intellectuals. People such as Stephen Spender, Robert Conquest, Ignazio Silone, Arthur Koestler, Raymond Aron, and others of the ‘God That Failed’ generation.

University of Canterbury philosophy academic Mike Grimshaw.

The congress achieved notoriety in 1966 when it was revealed to be largely funded by the CIA, established after World War II in parallel with other anti-communist ‘front’ organisations, including the US Information Agency.

Grimshaw is not advocating for CIA or aligned funding; only that a new organisation to support liberalism – in the classical definition – against the illiberal forces represented by the woke ‘cancel culture’ on the left and the Trumpian views of the alt-right.

As Grimshaw states, the legacy of the original congress has been well documented, and I’ll be covering that later. Communism and Marxism have lost their attraction to most intellectuals, while the reputations of those funded (often without their knowledge) by the CIA have been vindicated by history.

Although Encounter disappeared in 1991, with the collapse of the Soviet Union, some of the congress’s affiliated publications, such as Australia’s Quadrant, Partisan Review and China Quarterly, continue to exist with different sponsors.

Grimshaw sees new dangers to freedom in the growth of nihilism and anti-democratic views that have replaced the failures of the socialist and fascist nirvanas. Examples are authoritarian ideologies based on ‘identity’ issues such as race, religion, and nationalism.

English academic and author David Caute.

His call comes 20 years after the publication of David Caute’s The Dancer Defects, an exhaustive study of the struggle for cultural supremacy between the West and the Soviet bloc from 1945 to 1990. Caute was a fellow at Oxford’s All Souls College from 1959 to 1965 and a prolific author of fiction (13 novels) and non-fiction (17 titles since 1964), most of them concerned with Cold War issues.

He has written extensively on witch hunts against communist sympathisers and his best-known work is The Fellow Travellers (1973). He uses that term in its non-pejorative sense of those in the Enlightenment tradition who sympathised with socialism but either adapted or rationalised their thinking when faced with the unpleasant facts of its reality.

The Dancer Defects runs to nearly 800 pages, including 200 of notes, sources and bibliography. It’s more detailed than Martin Sixsmith’s recent The War of Nerves (2021), a history of the psychological dimensions of the Cold War, which produced the now-common concepts of disinformation and misinformation, cyber warfare, and propaganda campaigns.

Though the title recalls the high point of the cultural Cold War – the defection of Kirov Ballet star Rudolf Nureyev in 1961 – Caute’s account starts with the hesitant cultural exchanges between the two victorious power blocs after World War II.

Before 1939, the Soviet Union had cut itself off culturally from the West, with limited travel by artists and heavy censorship during the Stalinist era. The short-lived Nazi-Soviet pact in 1939-41 further tested the loyalties of the communist movement in the West, before reversing into an uneasy wartime alliance.

Rudolph Nureyev. Photo: Allan Warren.

The cultural side of the Cold War ran the full gamut of literature, theatre, fine arts, ballet, classical music, jazz, rock concerts, national exhibitions, architecture, and even chess because both the liberal democratic and socialist intellectual systems had a common heritage – in name if not practice.

But by insulating itself, the Soviet Union, more so after the addition of other Eastern European countries behind the Iron Curtain, took an aggressive stance against what it considered the ‘decadent’ West.

“No previous imperial system had involved furious disputes in genetics, prize-fights between philosophers, literary brawls capable of inflicting grievous bodily harm, duels with paint-brushes, the sending home of ballet companies without a single pirouette being performed …” are just some examples Caute cites and describes.

There’s more: defecting cellists, the theft of musical film scores, chess teams refusing to travel because of fingerprinting, jammed radio broadcasts, literal iron curtains against the sound of rock music, and the padlocking of avant-garde paintings.

The Western media was constantly full of persecution stories in the Soviet Union and its satellites. Writers such as Pasternak, Solzhenitsyn, Sinyavsky and Daniel; the scientist Sakhanov; musicians Shostakovich, Prokofiev, and Rostropovich; and, of course, the defecting dancers were household names in the West and symbols of an unfree society.

Caute examines the plight of Soviet theatre, which banned the works of Americans such as Tennessee Williams and Eugene O’Neill but was happy to stage anything that highlighted racial and social problems in the West. By contrast, Western critics, and some Russian ones, viewed Soviet plays as relentlessly positive, lacking in tension, drama and conflict.

Julie Christie and Omar Sharif in the movie of Boris Pasternak’s ‘Dr Zhivago’.

The cinema wasn’t much different. Soviet movie output took a while to recover from the war and it wasn’t until after Stalin’s death in 1953 that a handful of movies became noticed in the West, all with wartime themes. Caute notes the lack of individual dilemmas in the content and the widening gap in technique as European cinema went through its modernist stage in the 1960s with Antonioni, Bergman, Fellini, and the French new wave.

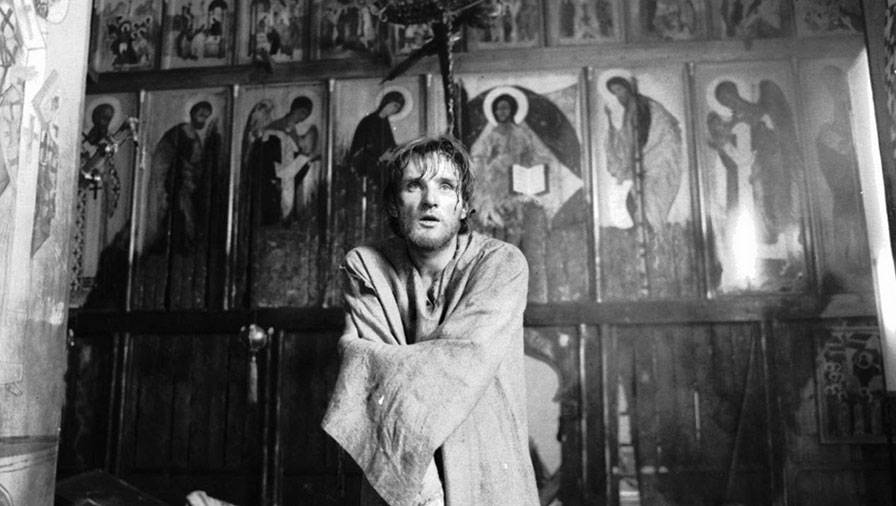

The one great modern Soviet director, Andrei Tarkovsky, made his first film, Ivan’s Childhood, in 1962 but his Andrei Rublev, made in 1965, wasn’t released until 1973. He was exiled in 1982.

Caute doesn’t ignore the Western side of the equation: Hollywood’s blacklisting of communist sympathisers and the House Un-American Activities Committee’s investigations. He examines the treatment of leading figures such as Arthur Miller, Elia Kazan, Joseph Losey, and Bertolt Brecht – the German playwright, who fled the US in 1947, eventually settling in East Germany in 1949.

Brecht and his collaborators get an entire chapter to themselves, with Caute being equivocal on whether the greatest ever communist writer was an opportunist, a hypocrite, or merely a master of dialectical flexibility. His impact on 20th-century theatre was undeniable, yet he had zero effect on the Kremlin’s commissars in Moscow. None of Brecht’s work was performed there during his lifetime.

A scene from Andrei Tarkovsky’s ‘Andrei Rublev’.

From Brecht, Caute moves to another of communism’s other intellectual giants, the French existential philosopher and writer Jean-Paul Sartre. Along with his one-time colleague, Albert Camus, Sartre was among the most influential thinkers of his time, as well as a prolific producer of novels and plays.

His dramas were about means and ends, subjects that were rarely discussed in the black-and-white world of Moscow’s theatre. By 1956, when Soviet troops entered Hungary, Sartre had joined Camus in rejecting most aspects of Soviet life.

The 1950s also saw the flourishing of ‘absurd’ theatre and abstract art, which were celebrated in the West as much as they were an anathema in the East. These artistic phenomena of modernism contrasted with the Soviet adherence to classical forms of music and ballet, the only areas where Russian artists excelled over their Western counterparts.

Caute is at his best in describing the latter decades of the Cold War, with the ballet defections, the exile of a generation of intellectuals, half-hearted ‘thaws’ that allowed some flowering of artistic achievement, and the initial cracks in the Iron Curtain from Polish cinema, Czech absurdist theatre, and Moscow’s dissident admirers of Picasso, another shunned communist.

Looking back, Caute says there are no clear winners or losers in a cultural war; they are like judgmental contests in dancing or diving; if the West 'won" it was more by default than achievement. The West could not match Brecht, the Bolshoi and the Kirov, or the Moscow Art Theatre (for its ensemble acting).

Nor did it have musicians of the calibre of Oistrakh, Richter and others already named, or the grand chess masters (with the exception of Fisher).

Caute is scathing in his dismissal of those who focused on the funding sources for the West’s cultural resistance to communism. This presented a “lopsided view of cultural activity” by aligning those artists with a conspiracy with the national security state rather than recognising they acted with individual conviction.

The parallel Grimshaw recognises is that those same liberal convictions are again under threat from a new omniscient ideology.

The Dancer Defects: The struggle for cultural supremacy during the Cold War, by David Caute (Oxford University Press)

Nevil Gibson is a former editor at large for NBR. He has contributed film and book reviews to various publications.

This is supplied content and not commissioned or paid for by NBR.