Fear and hate: Defining the ‘radical right’

Academics describe ‘abject failure’ of extremist politics.

WATCH: NBR columnist Nevil Gibson speaks with Calida Stuart-Menteath.

Academics describe ‘abject failure’ of extremist politics.

WATCH: NBR columnist Nevil Gibson speaks with Calida Stuart-Menteath.

Swings in the political pendulum are a normal part of the democratic process. But analysis of the reasons takes longer to sink in.

On a global scale, New Zealand’s most recent election dumped a left-leaning government for one of the right. In Poland, the opposite occurred.

Naturally, the losing side constructs explanations that go beyond the norm of balanced commentary. The National-led coalition is being branded the most ‘right wing’ in recent history; that would depend on how long your historical perspective is, and is likely to be based on pre-existing political attitudes.

Seasoned commentators, born in the Baby Boomer generation, are unlikely to agree. You don’t have to take their word for it. The historical record shows few governments would fit the description of being radically right-wing in either the political, economic, or social sense.

Some have taken radical actions at various stages, usually in response to crises that have threatened the economy, such as industrial disruption or a fiscal calamity in which a government drastically cuts its spending. Left-wing governments seldom act that way.

For these reasons, books on radical right-wing movements have been scarce compared with those on the left, though this might be coloured by the political sympathies of those who write them.

Professor Paul Spoonley.

Distinguished Massey University Professor Paul Spoonley was the first to present a comprehensive view in The Politics of Nostalgia, based on his PhD thesis in the 1980s, and published in 1987. His underlying theme was the role of racism in extreme right-wing organisations, which – from the early colonial days into the 20th century – was mainly about controlling immigration from China.

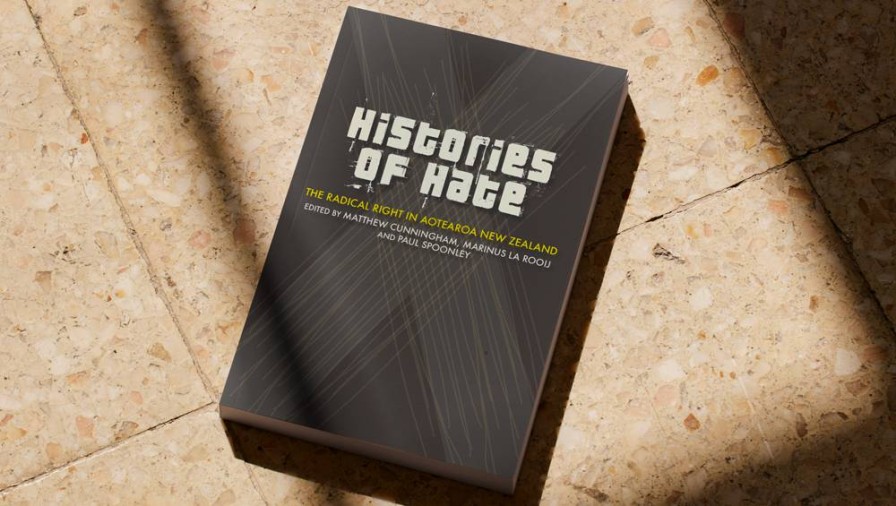

Spoonley has updated his work, in collaboration with two co-editors, Matthew Cunningham and Marius La Roou, as a contributor to Histories of Hate, a collection of 15 academic essays published last year amid a panic about the impact of America’s alt-right on the Government’s response to the Covid-19 pandemic.

The value lies in the historical perspective, which reinforces what the editors call the “abject failure” of radical right-wing politics to gain any substantial foothold in a country that was “isolated and self-contained” for much of its history.

The long arc indicates a collapse of anti-Chinese laws by the 1920s, a declining influence of anti-socialist causes up to the watershed election of a Labour government in 1935, and the long-standing obscurity of New Zealand’s few ideologists of antisemitism.

Arthur Nelson Field in 1993. Source: NZ Dictionary of Biography.

One of these, Lionel Terry, became infamous for his murder, in September 1905, of an “old and frail” Chinese person in Wellington. Terry was a promoter of Jewish conspiracies, mainly based on the use of imported non-white labour by mine owners in Canada and South Africa.

Terry’s prominence at the time was matched by Arthur Desmond, the author of Might is Right (1896), which is said to have inspired an attempted mass killing as recently as 2019. Desmond operated under the alias of Ragna Redbeard, a reference to Norse legend, and is apparently still admired in certain circles as a pioneer “radical fabulist”, according to his entry in the official NZ Dictionary of Biography.

Desmond’s contribution to international fascism is curious, to say the least. He sent one of his manifestoes to Russian writer Tolstoy, who was not impressed.

A third member of this tiny gang is Arthur Nelson Field, born in Nelson and who became one of the world’s leading proselytisers of Jews as both promoters of communism and capitalism.

The biographical profiles of these characters are among the liveliest chapters, leavening the drier patches tracing the rise and fall of the anti-socialist New Zealand Welfare League, its successor the New Zealand Legion, and the anti-Catholic (and Irish) Protestant Political Association in the 1920s and 1930s.

While warning of the combined evils of Bolshevism, Catholicism, and class warfare – mainly through public meetings and newspaper op-eds – these groups also campaigned on moral issues such as abortion, homosexuality, and same-sex marriage. Again, these became failed causes when they were picked up again in the 1960s.

The end of World War II unleashed forces that eventually ended Labour’s 15 years in power. But the desire for more economic freedom and fewer government controls did not come from the radical right, whose fascist links had died in the war. So had the ideas of human development through eugenics, common in the 1930s in places such as Sweden and influential in Labour’s public health policies.

Two Social Credit MPs, 1984: Neil Morrison, left, and Garry Knapp with leader Bruce Beetham, centre.

The emergence of the Cold War offered opportunities for anti-communist purges in the public service and trade unions. But no-one on the far right was motivated enough to counter the strength of the pro-Soviet ‘peace’ movement. The best the editors could find are supporters for the retention of ‘white rule’ in South African and Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe).

Another area given the spotlight was a revival in the 1950s of Arthur Field’s antisemitic polemics in the 1930s promoting the monetary ideas of social credit. They were embraced by the League of Rights and became the basis of a political movement that attracted many followers, mainly from rural areas, as had happened in North America in the Great Depression.

But, despite its origins in the Jewish money conspiracy, Social Credit’s political impact was generally regarded in New Zealand as more centrist and state-activist than National’s inherent conservatism.

A more obvious example from the 1960s were the rebellious youth who adopted the uniforms and outward insignia of Nazi Germany, the most outrageous form of protest you could have against respectable society. Yet these were more expressive of a ‘skinhead’ street gang culture based on imported than a genuine grievance.

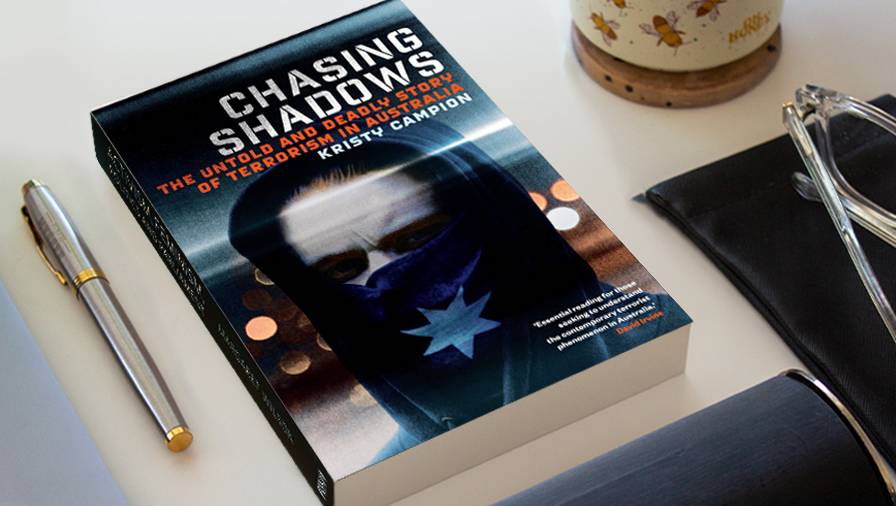

Chasing Shadows: The Untold and Deadly Story of Terrorism in Australia, by Kristy Campion.

A recent Australian book on neo-Nazi movements (Chasing Shadows), by an expert in police surveillance, showed while they have a high profile in generating public fears, their longevity is less certain.

Moral campaigners also gain more than their share of attention, on issues such as pornography, abortion, and homosexuality, but whether they can be lumped in with other radical right causes depends on where you draw the line. Fundamentalist Christian groups were identified in Byron Clark’s Fear as examples of extremist threats.

But this was an intellectual stretch and their inclusion in Histories of Hate may reflect the mere existence of research on religious cults rather than their political relevance.

A more fruitful source in recent years for the academic contributors has been to brand the radical right through identity politics and critical race theory. This was made easier by the Christchurch mosque attacker, who drew on Islamic threats to the racial and religious purity of European civilisation that echoed those of Ragna Redbeard and his Norse gods back in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

More recently, this has been raised by the illegal mass migration to Europe of Muslims and other non-white ethnicities seeking better lives than can be provided in their own countries. Anti-immigrant parties make up about 20% of the European Parliament and have governmental roles in countries as varied as the Netherlands, Sweden, and Denmark, or Italy, Austria, and Hungary.

The fortunes of these parties have differed according to democratic outcomes but, overall, their popularity is rising. Some may still deserve the radical right label, but that definition remains moot as anti-immigrant views again become mainstream, as they were a century ago.

The editors reject the notion of the Christchurch terrorist attacks as a linear development from this country’s history of ‘white supremacy’ – though some of the contributors are more comfortable with applying modern attitudes in judging the past. This is apparent in a chapter on “anti-Treaty” historians who have not bought into court-sanctioned principles that are still hotly debated today.

The editors describe right-wing extremism, in all its diversity, as a constantly changing phenomenon while retaining a typically common academic perspective that views anything ‘populist’ as abhorrent. Future histories of the ‘radical right’ will face the same dilemma, as what is acceptable to the mainstream moves between extremes on a crowded spectrum that has many more facets and platforms than it had in the past.

Histories of Hate, edited by Matthew Cunningham, Marius La Roou, and Paul Spoonley (Otago University Press).

Nevil Gibson is a former editor at large for NBR. He has contributed film and book reviews to various publications.

This is supplied content and not paid for by NBR.

Sign up to get the latest stories and insights delivered to your inbox – free, every day.