Life slowly returning to ‘new normal’

Outward migration will drive political debate through to the next election.

Outward migration will drive political debate through to the next election.

Just as Australian visitors are now being welcomed to New Zealand, officials are warning tens of thousands of New Zealanders could head overseas in the next year as border restrictions ease.

If the numbers are right – they range from 50,000 to 120,000 – it could exacerbate New Zealand’s already tight labour market and skills shortage.

Much will depend though on how many migrants come the other way. If New Zealand’s borders open up and this country remains an attractive destination – as it was before the Covid-19 pandemic – then those leaving might be more than compensated by those arriving.

The political arguments around this will run right through to next year’s election, with Opposition parties blaming the Government for the expected exodus. They say people want to leave to get cheaper housing, a lower cost of living, and higher wages.

Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern’s retort is that it is simply life returning to normal as Kiwis follow their rite of passage by going overseas.

Both are partly right.

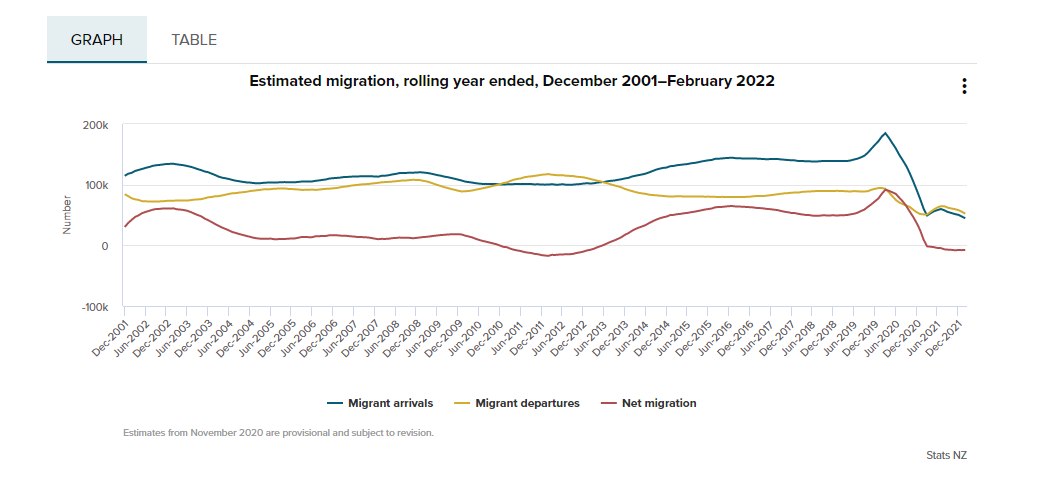

The latest migration figures for the year to the end of February recorded 44,500 migrants arriving here, while 52,200 left, representing a net annual migration loss of 7600.

Both migrant arrivals and departures slumped abruptly following the closure of borders at the beginning of the Covid-19 pandemic. Before then there had been strong migrant inflows, with the net migration gain rising close to 100,000 at the end of 2019.

Last migration slump

The last time migration flows had slumped had largely been in 2011 and into 2012 as the effects of the global financial crisis were felt.

Following that, migrant departures remained steady while arrivals kept increasing, leading to big net migration gains from the end of 2013 onwards until Covid-19 hit.

More than two years of restrictions have largely kept migrants out, with most of those arriving here have been New Zealanders returning from overseas, and kept Kiwis here – particularly younger people who traditionally would have gone away on their OE.

That pent-up demand is likely to be behind at least some of the expected outwards migration officials are now forecasting for the next year.

But it is clear others are also looking to move to countries where housing might be more affordable and wages higher. That represents not just a problem for the Government but also for employers crying out for workers.

Everyone seems to agree that lifting wages here is one part of the response, but there seems to be disagreement about how to do that.

Act leader David Seymour believes cutting taxes, removing red tape, and making life easier for employers would help. He rejects the Government’s approach of increasing the minimum wage and introducing legislation for fair pay agreements.

But the onus might also be on employers – if they are desperate for skilled staff – to offer better rates of pay. This has already happened in the tech sector, which is desperately short of workers. Industry lobby group NZTech surveyed members last year and found of the 271 respondents, two-thirds of those were paying more than double the medium wage – more than $112,000.

Child poverty

Meanwhile, Ardern was taking credit for her Government meeting some of its targets on reducing child poverty in a press release titled ‘Government delivering improvements to children’s lives’. It stated there had been a 25% reduction in children aged 0-14 living in households where food ran out sometimes or often in 2020-21 compared with a year earlier.

As well, there had been a 30% reduction over three years from 2017-18 in children aged 0-17 who lived in low-income households after housing costs and 92% of young people aged 15-24 reported their health as good, very good, or excellent in 2020-21. Other indicators for the year were also more positive.

But critics, including the Child Poverty Action Group, said the numbers were dated and that the Covid-19 pandemic had had a negative impact on many low-income households.

The numbers, though, are just really a year out of date but they do not pick up the rapid rise in inflation over the past year, which surely has had a detrimental effect on household wellbeing.

In her statement, Ardern said there was no silver bullet to fix the long-term disadvantages faced by many households.

“But the range of measures contained in our plan are making a difference. Our families’ package and other measures – like lifting the minimum wage and benefits, expanding free lunches in schools, making doctors’ visits free till the age of 14, and expanding primary mental health services – are making a difference and there is clear evidence they are improving the lives of many children,” she said.

National’s child poverty reduction spokesperson Louise Upston disagrees, saying Labour had totally failed to address child poverty.

“Housing isn’t getting any more affordable under Labour’s watch either, with the latest Child Poverty Related Indicators Report showing no improvement in housing affordability. This is a direct result of Labour’s failed housing policies.

“On top of that, Labour has overseen the worst cost-of-living crisis in a generation, which is hitting lower-income families the hardest,” Upston says.

More pain on the way

Many households face more pain as the Reserve Bank pushed up its official cash rate from 1 to 1.5% and continued to signal more rate rises were on the way. That will drive up mortgage rates, making life tougher for those households with large mortgages and who face rolling over fixed-rate mortgages this year.

On the positive side, though, it is already helping moderate house prices and should eventually also help rein in inflation. That might also increase unemployment, expanding the labour pool for employers looking for workers.

The next consumer price index for the year to the end of March is due out this Thursday and that figure is likely to make depressing reading. But, over time, prices increases will ease as higher interest rates take effect.

In a piece of good news for the hospitality sector at least, the country is now at the orange light setting of the Covid-19 Protection Framework, meaning bars, cafés, restaurants, and nightclubs can open without restrictions.

Meanwhile, in a further sign the country is reopening for business, Ardern and Trade Minister Damien O’Connor are in Singapore and Japan this week – with 13 business leaders in tow – in an effort to strengthen commercial and trade ties. It is the first in a series of overseas trips Ardern is expected to make this year to give impetus to New Zealand’s trade connections.

Slowly life is returning to some sort of new Covid ‘normal’.